November 21, 2023

#12: Local Actors and the Work of Investment Mediation in Australian Agriculture

Zannie Langford opens our new theme on “intermediaries” – a neglected class in research on the assetization of farmland and agriculture. She is a Research Fellow at the Griffith University Asia Institute, Queensland, Australia. Her research explores questions of how private sector finance has become entwined in the pursuit of rural development goals. In her new book Assembling Financialization: Local Actors and the Making of Agricultural Investment (just published in October with Berghahn Books), she explores how different forms of finance have become incorporated in rural agriculture in Northern Australia.

***

Assembling financialisation sets out to explore how finance makes its way into agriculture. This inquiry has led me into conversations with local people who work at the interface of finance and rural spaces, who are involved with negotiating with various stakeholders to make deals in pursuit of a range of different goals. In doing so they apply different value judgements and moral reasonings and draw on a range of local and global tools. The research pursued a key question: to what extent do local people play a role in facilitating agricultural investment and negotiating the form that it takes?

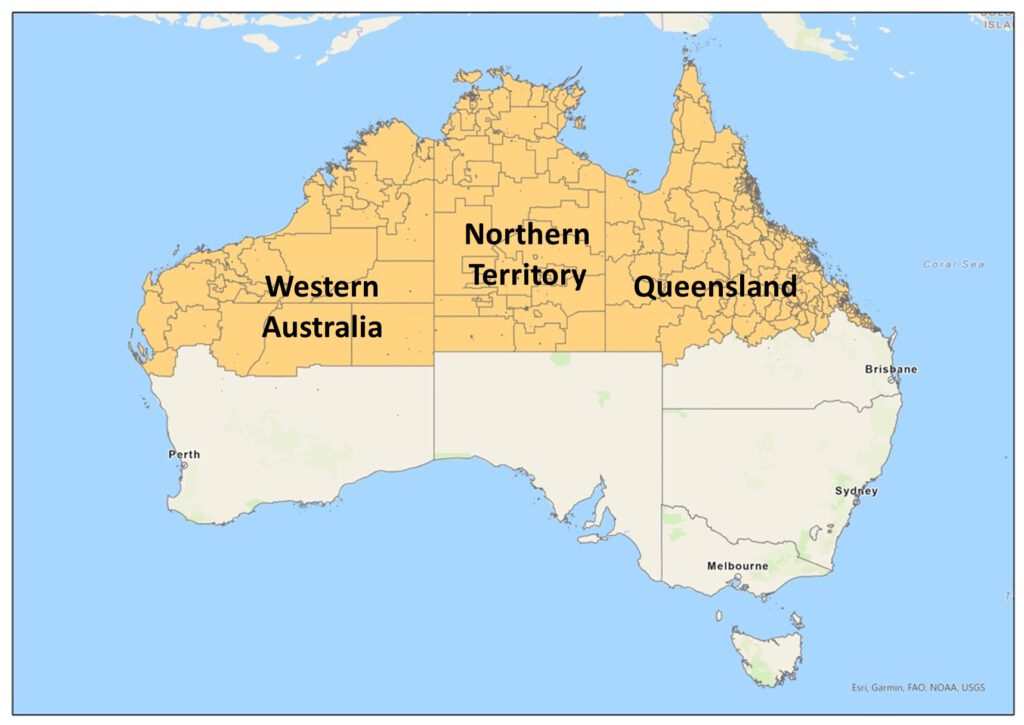

The location of this body of work is Northern Australia (see figure below). Northern Australia is an interesting place to study the work of local people (and nonhuman actors), because it is a place where these actors often have more power than in other locations. Northern Australia is a large, remote region which is primarily used for cattle grazing, although there are also attempts to ‘develop’ the region through more intensive use of the land for agriculture, aquaculture, horticulture, and forestry. In this context, there are far fewer farming professionals than in established farming regions in southern Australia, and those that are successful possess specialist knowledge that is of great value to potential investors. It is therefore a site where people with specialist local knowledge hold particular power to wield this knowledge in negotiations with investors.

Region of Northern Australia (shown in orange) as defined by the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility [1]. Map: created by Zannie Langford in ARCGIS Pro.

A strategy for Northern Australian development is outlined in the White Paper on Developing Northern Australia [2], which claims that:

It is not the Commonwealth Government’s role to direct, or be the principal financier of, development. Developing the north is a partnership between investors (local and international investors who provide capital and know-how) and governments (that create the right investment conditions).

The White Paper articulates what might be considered a ‘financialising’ form of governance [3], which attempts to outsource rural development not just to the private sector, but to the financial sector. This approach has seen government officials focus attention on attracting large-scale investment in agricultural, horticultural, forestry and aquacultural projects. However, Northern Australia is also the site of investment failure. Numerous large-scale investment schemes have been attempted over the last fifty years, including a couple of notable recent examples: the proposed US $1.5 billion dollar project Sea Dragon, which sought to develop the largest prawn ponds ever attempted in Australia on a remote cattle station on the Northern Territory border, and has since been deemed unviable [4], and the managed investment scheme Quintis sandalwood, which was subject to short selling, recapitalisation, and recently, sell-off of a number of their Northern Territory properties for land-clearing after their plantations failed to perform [5]. Northern Australia has long been a place of booms and busts [6], with many examples of failed agricultural schemes. Throughout this, the cattle grazing industry has persisted, yet it is also increasingly subject to high and volatile land prices as investors seek to capitalise on land price cycles. Indeed, most foreign land ownership in Australia (by area) is cattle grazing land and is owned by a small number of large cattle companies [7].

In this context, what can be learned about agri-food financialisation from a focus on individuals? My research has shown how local actors can – but don’t always – shape the form of investment in significant ways. This can occur in a range of ways.

Local actors on a cattle property in Northern Australia. Source: Zannie Langford.

Family farms, for example, are often a target for investment, and many are increasingly hoping to attract an equity investor to alleviate their reliance on debt financing. They hope that such an investment would provide the capital needed to grow and develop their business and alleviate the stress of debt financing which is often available on unfavourable terms. The Australian government promotes this approach, noting that in order to fill an estimated $600 billion ‘capital gap’ needed to fund the growth and modernisation of Australian agriculture, the state will support farmers to ‘consider their investment options and business structures and develop the skills and expertise necessary to work with external investors’ [8]. Yet in talking to farmers during my research, most farmers expressed a desire to attract such investment but had little understanding of how to go about it. I found one case of a highly successful ‘capitalised farm family entrepreneur’ [9] who managed to attract investment from a large institutional investor, but to do so had spent millions of dollars, over a number of years, through high-level negotiations that required one family member to acquire advanced financial skills in order to bridge the gap between investor requirements and the practicalities of managing cattle farms. The result was a joint venture that has gone on to build an integrated cattle company, funded by the investor and led by the expertise of members of a multigenerational cattle family. This partnership was possible – and necessary – because there are few people with the expertise necessary to manage such an operation, making the family farmers essential to the investor’s strategy. Their story also highlights the limits of a model such as this for a broader cohort of Australian cattle farmers, few of whom have the financial resources, capacity, and inclination to pursue such a strategy.

Rather, most family farmers will be incorporated into investor schemes through other mechanisms (perhaps staying on as managers without owning a stake in the business) or will continue to rely on bank debt. But banks are also undergoing processes of financialisation. In Australia, a recent Royal Commission [10] into misconduct in the banking sector revealed instances of manipulation of land values by bankers to support increased lending to farmers above sustainable levels. In such cases bankers would deliberately overvalue a pastoral station so that they could lend the pastoralist more money at bank-approved lending rates, thereby increasing their lending portfolio and earning performance bonuses from the bank. This created issues for farmers later on, if a drought or other circumstances caused the property valuation to be revised. Farmers would find themselves overextended and unable to borrow additional funds, which they need during drought for additional costs such as to purchase supplementary cattle feed. The findings of the Royal Commission led banks to revise their policies and place additional restrictions on rural lenders. My research with bankers revealed important differences in banker behaviour that was linked to their residence in the region. Some bankers were relocated to the region during times of financial expansion on short-term contracts, and during this time worked aggressively to expand their lending portfolio. Others were long-time residents of the region, had worked there for a decade or more with many of the same farmers. The former tended to be more aggressive and lend at riskier propositions, while the latter were more cautious in their dealings and often lent below allowable levels. I suggested that the geographies of northern Australia and the long-term relations they created were generative of a moral economy [11], where bankers exercised care for their clients and sought – often explicitly – to moderate debt markets during times of financial growth.

An awareness of market cyclicality is evident not only among bankers, but also among land valuation professionals. There are few rural land valuers in remote northern Australia, and the field is highly specialised. Knowledge of the nuances of the region is needed to accurately assess property values. This is particularly true in the context of agricultural development efforts – traditionally, most of the land in the region has been cattle grazing land, but this is changing with efforts to develop new projects on parts of properties. Cattle prices have become increasingly high and volatile over time, particularly for larger, corporately owned properties. Traditionally, cattle grazing land has been valued based on an estimate of the number of cattle that can sustainably live on it (the ‘Beast Area Value’ method), rather than using the ‘Return on Investment’ method which is common for other projects. Some large cattle companies have found that they can install additional water infrastructure on a property to increase the number of cattle that can live on it, thereby raising the value as calculated using the Beast Area Value method – even if such developments do not necessarily increase the profitability of a property. I suggest that this can be thought of as a kind of ‘speculative development’ which undertakes property development as a speculative venture [12]. Some land valuers express an awareness of their own role in creating value, seeking to moderate land markets to ensure that ‘the market’s not getting out of whack’.

Agricultural developments on land were also pursued by Indigenous corporations, who widely sought to develop profitable businesses to support employment opportunities and wealth generation for their constituents [13]. This business development activity has often been viewed as ‘the next phase of land rights in Australia’ [14] and across Australia there is widespread support for Indigenous business development as a wealth and employment-generating activity [15]. These organisations, and the intermediaries who work with them, seek to assemble land-based assets in forms that will attract investment, often building investment prospectuses to market opportunities available on their land to prospective investors [16]. In doing so they hope to create local economic growth and employment opportunities, and to relieve themselves of reliance on cyclical government funding. Yet they have often had trouble attracting investment in agricultural opportunities due to many of the same issues faced in attracting investment on non-Indigenous land – remoteness, lack of transport infrastructure, high costs of trade, unsuitability of soil and water combinations for agriculture – as well as additional issues such as labour force availability. Asset-making in such situations is an uncertain and reversible process, and it is not the case that the openness of landholders to investment has led to a rapid influx of development proposals. In such cases, government support looks to be necessary to support most types of enterprises into the future.

Local people play an important role in shaping the form that investments can, and (when successful) do, take in Northern Australia. My book suggests that this can be usefully understood by applying an assemblage approach to the study of financialisation. An assemblage approach positions local actors as potential sites of power in negotiating connections between local spaces and global finance. Through attention to the work of these local actors, I argue that while financialisation is a useful signifier of patterns of global change, it can also be understood as an assemblage of moments of negotiation and contestation between locally-embedded actors. Attention to the work of these actors and the outcomes they produce can support a more grounded policy on Northern Australian agricultural development, sensitive to the range of ways that finance-driven agri-food transformations occur at the local level.

[1] Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (2023) About Us. Available at: https://naif.gov.au/our-organisation/about-us/ (accessed:21/11/2023). [2] Australian Government (2015a) Our North, Our Future: White Paper on Developing Northern Australia. Available at: https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/our-north-our-future-white-paper-on-developing-northern-australia (accessed:21/11/2023). [3] Langford A, Smith K and Lawrence G (2020) Financialising governance? State actor engagement with private finance for rural development in the Northern Territory of Australia. Research in Globalization 2(100026): 1-9. DOI: doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2020.100026. [4] Seafarms Group (2022) Project Sea Dragon Review – Investor Briefing Presentation. Available at: http://seafarms.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Project-Sea-Dragon-Review-Investor-Briefing-Presentation-March-31-2022-1.pdf (accessed:11/10/2023). [5] Brann M (2022) Indian Sandalwood Company Quintis Puts Northern Territory Farm on Market. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2022-08-18/quintis-indian-sandalwood-farm-mataranka-for-sale/101337754 (accessed:16/03/2023). [6] Langford A (2020) Agri-food transformations in Northern Australia: The work of local actors in mediating financial investments. PhD Thesis, School of Social Science, University of Queensland. [7] Smith K, Langford A and Lawrence G (2023) Tracking farmland investment in Australia: Institutional finance and the politics of data mapping. Journal of Agrarian Change 23(3): 518-546. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12531. [8] ANZ (2012) Focus Greener Pastures: The Global Soft Commodity Opportunity for Australia and New Zealand, Issue 4. Available at: https://bluenotes.anz.com/posts/2012/10/greener-pastures (accessed: 16/03/2023). Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (2018) Agricultural Lending Data 2016–17. Commonwealth of Australia. Available at: http://www.agriculture.gov.au/ag-farm-food/drought/agricultural-lending-data. (accessed: 16/03/2023). [9] Langford A (2019) Capitalising the farm family entrepreneur: Negotiating private equity partnerships in Australia. Australian Geographer 50(4): 473-491. DOI: doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2019.1682320. [10] Commonwealth of Australia (2019) Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry. Available at: https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/fsrc-volume1.pdf (accessed: 16/03/2023). [11] Langford A, Brekelmans A and Lawrence, G. (2021) I want to sleep at night as well: Guilt and care in the making of agricultural credit markets. In: Prince R, Henry M, Gallagher A, et al. (eds) Markets in their place: Context, Culture, Finance. London: Routledge, chapter 7. DOI: doi.org/10.4324/9780429296260. [12] Langford A (2022) A ‘Rule of Thumb’ and the Return on Investment: The role of valuation devices in the financialisation of Northern Australian pastoral land’. Valuation Studies 8(2): 37-60. DOI: doi.org/10.3384/VS.2001-5992.2021.8.2.37-60. [13] Langford A, Lawrence G and Smith K (2021) Financialisation for development? Asset-making on Indigenous land in remote Northern Australia. Development and Change 52(3): 574-597. DOI: doi.org/10.1111/dech.12648. [14] Australian Government (2015) COAG Investigation into Indigenous Land Administration and Use. Available at: https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource-centre/indigenous-affairs/coag-investigation-indigenous-land-administration-and-use. (accessed: 16/03/2023). [15] Langford A (2023) The geographies of Indigenous business in Australia: An analysis of scale, industry and remoteness. Supply Nation Research Report 8. Available at: https://supplynation.org.au/research-paper/the-geographies-of-indigenous-business-in-australia-an-analysis-of-scale-industry-and-remoteness/ (accessed: 21/11/2023). [16] For example, see: Land Development Corporation (2017) Tiwi Islands Investment Opportunity. Available at: https://www.tiwilandcouncil.com/documents/Uploads/LDC_Tiwi%20Islands_PrivateSectorInvestmentOpportunitieslr.pdf (accessed: 26/11/2023).