September 27, 2025

#27 Land and Power: Inside the Rise of the World’s Transnational Landowners

The accumulation of vast tracts of land by a small group of global corporate landowners is deepening inequality and accelerating the climate crisis. This is the central warning of a new report by FIAN International and Focus on the Global South, which calls for bold land redistribution and global tax reforms to reverse this dangerous trend. Two of its co-authors, Philip Seufert and Luciana Rolon, provide insightful reflections.

***

A Global Land Grab that Mirrors Rising Inequality

Over the past two decades, vast tracts of land—particularly in the Global South—have been bought up by international investors and ultra-rich corporations. As land control shifts into the hands of powerful, opaque, and transnational actors, inequality deepens and public regulation weakens. This is not just about ownership, but about power—who gets to decide how land is used, and who suffers the consequences. The growing dominance of corporate and financial actors brings forced displacements, environmental degradation, and violence, disproportionately affecting women and rural, Indigenous Peoples, and peasant communities. It also undermines state sovereignty and the ability of governments to regulate land and other natural resources in the public interest. While not new, these dynamics have been amplified by the financialization of land—its transformation into a speculative asset class within global investment portfolios. This article presents key findings from Lords of the Land: Transnational Landowners, Inequality and the Case for Redistribution, which sheds light on this hidden process by identifying the major transnational actors driving land concentration and proposes concrete policy measures aimed at redistribution and fiscal justice.

The Financialization of Land: A Growing Trend

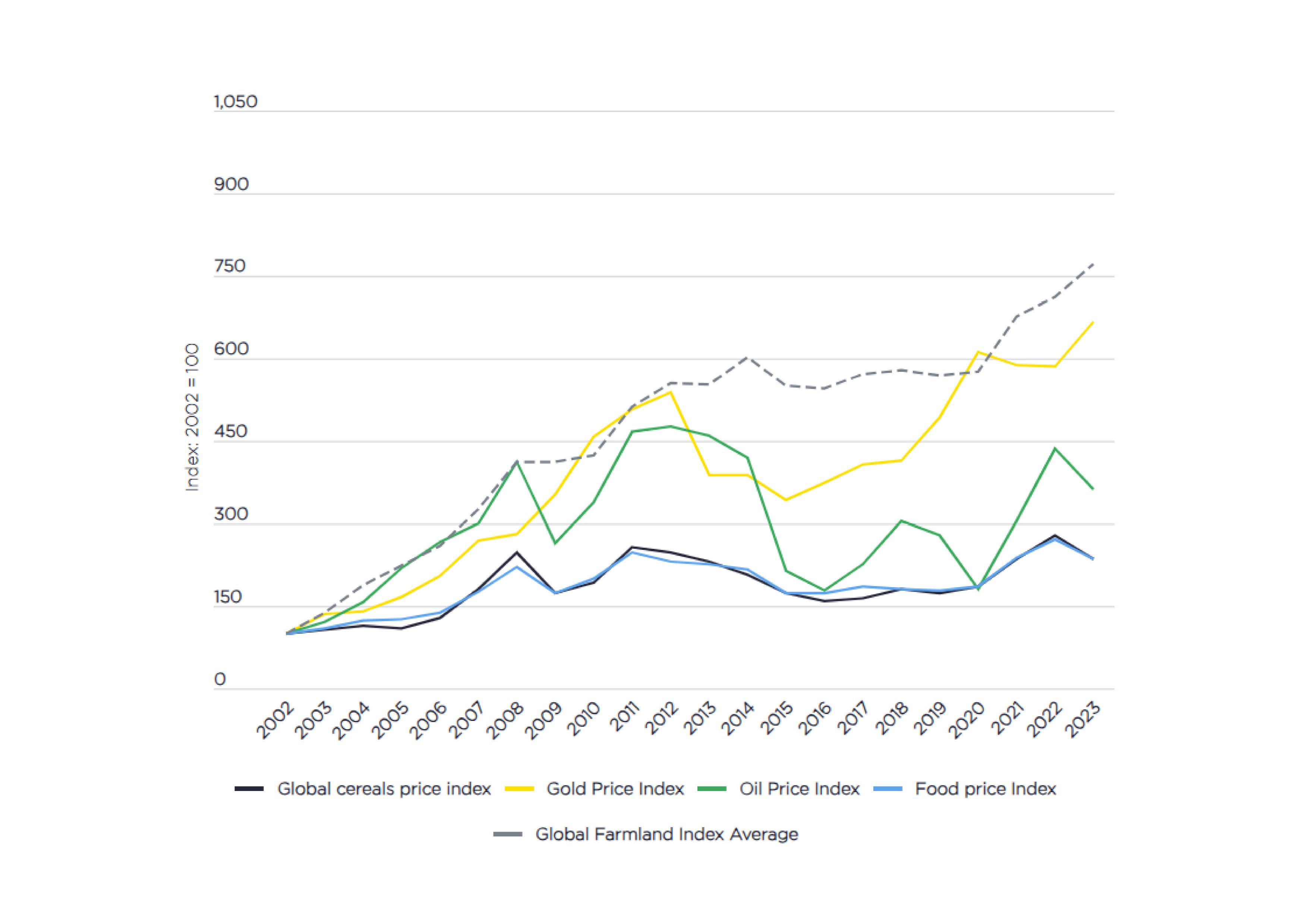

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, land has increasingly been treated as a financial asset—valued for its long-term appreciation, inflation-hedging potential, and perceived stability. This shift has attracted new actors such as asset managers, pension funds, and ultra-wealthy individuals, many of whom operate in the Global South through opaque structures or partnerships with local corporations. These investments are often linked to large-scale industrial agriculture, land-use transformation, leasing schemes, or carbon offset projects. While some data exists on land use, reliable information about ownership and corporate control remains scarce. Agricultural censuses typically report on farm operations rather than legal ownership. As a result, the true extent of corporate and financial control is difficult to assess. Still, the available data offers important clues: according to a recent analysis, just 1% of the largest farms control 70% of the world’s agricultural land, while farms under 2 hectares—making up 84% of all farms—access only 12% of it [1]. The appeal of farmland for investors becomes even clearer when looking at long-term return trends. Farmland has consistently outperformed key commodities like gold, oil, and agricultural products—making it an increasingly attractive asset class (as widely documented on this website). Farmland markets in 2023 grew at an average rate of 8.5%, delivering higher returns than food, oil, or gold.

Figure 1: Global Farmland Index and Key Commodity Returns. Source: Savills Research, FAO, OPEC, Macrobond [2]

Who Are the New Lords of the Land?

The Lords of the Land report identifies the ten largest transnational corporate landowners of agricultural land. These include financial entities such as Blue Carbon (UAE), the US pension fund TIAA, Macquarie (Australia), Manulife (Canada), and Edizione S.r.l., the holding company of the Benetton family. They also include agribusiness giants like Olam, and Wilmar (Singapore), Argentinian Cresud, Chile-based timber company Arauco, and Shell, through its Brazilian subsidiary Raízen. Together, these ten entities control over 404,457 km² of land—an area roughly the size of Japan, Zimbabwe, or Paraguay—with the vast majority located in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Although historical data is often scarce, many of these companies have significantly expanded their landholdings: Wilmar increased by 15% in the past 15 years; Cresud by 29%; and TIAA/Nuveen nearly quadrupled its holdings since 2012 [3].

Figure 2: Map of Transnational Landowners. Source: FIAN International [4]

While many of these companies are headquartered in the Global North, about 80% of the land they control is located in the Global South, reflecting a neo-colonial dynamic in which capital flows from the North are used to capture and control territory in the South. The profiles of these landowners also differ. Those based in the Global South tend to be directly involved in agro-industrial production, forestry, and bioeconomy sectors, while those from the North focus more on generating rents and asset appreciation. A particularly revealing case is Blue Carbon, which tops the list and alone controls more than half the total land area identified in the report. Founded in 2022 and backed by a member of Dubai’s royal family—whose business interests also include fossil fuels—Blue Carbon has signed agreements for 24.5 million hectares across strategic regions of Africa and the Asia-Pacific, often targeting forests, mangroves, and coastal ecosystems—key carbon sinks now commodified in global offset markets [5]. This case—and that of Manulife, which markets itself as the world’s second-largest “natural asset company” [6] —illustrates how new investment frontiers like carbon and biodiversity markets create fresh incentives for land grabbing and inequality. Long-term leases and exclusive usage rights often displace communities indirectly while turning nature into a commodity.

Many of these companies have a documented track record of environmental destruction and conflict with local communities. For instance, TIAA has acquired 61,000 hectares in Brazil’s Cerrado region—one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems. Around half of the Cerrado has been converted into monocultures, tree plantations, or pastures, with serious consequences for biodiversity, climate, and land conflicts [7]. Meanwhile, asset managers like BlackRock and Vanguard are key shareholders in several of these firms, playing an indirect but powerful role. In recent years, partnerships between agribusinesses and investment funds have intensified, enabling further expansion, land-use conversion, monoculture plantations, and speculative real estate ventures. In every case, land control is increasingly moving away from the people who live and depend on it.

The “Making of”: Uncovering What Is Meant to Stay Hidden

Uncovering who truly controls vast tracts of land required navigating opaque structures, scarce records, and deliberately complex ownership arrangements. To do so, we applied what we called a “puzzle methodology”—a multi-source strategy that cross-verified information from academic research, NGO and media reports, collaborative global databases such as Land Matrix, corporate and financial documents, and interviews with experts, including scholars, activists, journalists, and public officials. We focused on transnational corporate and financial actors and excluded domestic firms and sectors like mining, tourism, or residential real estate due to limited public data. We prioritized legal ownership and long-term concessions, and ranked companies by hectares controlled, a standardized and verifiable metric. One key challenge was deliberate opacity. Many firms operate through holding companies in tax havens or joint ventures that obscure ownership. For public companies, we used annual reports. For asset managers, we relied on investor reports disclosing farmland assets selectively. Ultimately, we consolidated a list of major transnational landholders, validated figures through company data, and invited their comments.

Social, Ecological and Fiscal Impacts

The concentration of land in the hands of a few has far-reaching consequences: growing inequality in land access and wealth, environmental degradation, displacement of local communities, and a weakening of state capacity. Several of the companies named in the report have been linked to human rights violations and large-scale deforestation. Transnational land ownership—often structured through offshore entities—also undermines effective taxation. As a result, those who hold the most land often pay proportionally less, while small-scale producers face higher relative tax burdens. In other words: increased corporate control over land is compounded by a fiscal transfer of wealth from the bottom to the top. In a context of sovereign debt crises, capital flight, and fiscal constraints, restoring the state’s ability to generate income through the progressive taxation of land, wealth, and emissions is essential—not only to reduce inequality but to fund redistributive policies and just ecological transitions.

Alternatives: Toward Just Redistribution and Greater International Cooperation

Most policy responses to corporate land grabs have been weak or merely palliative. Mitigation of the most extreme excesses is not enough. The scale of the problem calls for a shift in public policies toward redistribution. This means reviving redistributive agrarian reform—a historically central tool to reduce inequality, secure land rights, and democratize access to resources. Today, it must be reimagined through lenses of ecological transition and fiscal justice.

The Lords of the Land report proposes four lines of action: • Improve transparency and monitoring: Ensure public access to data on land ownership and the financial structures behind major landholders. • Regulate and hold accountable: Enforce binding legal frameworks to ensure corporations respect human and environmental rights—and penalize abuses and crimes. • Implement progressive taxation: Introduce taxes on land, wealth, windfall profits, and emissions, reversing today’s regressive and evasive tax architecture. • Reactivate redistribution processes: Reverse land concentration through ownership caps, restitution, recognition of collective tenure, and expropriation of lands linked to tax havens or rights violations.

These measures cannot depend on national action alone. Land financialization is a transnational process driven by global capital. Stronger international cooperation is essential to regulate corporate power, curb tax evasion, and expand the fiscal space needed for just transitions. As the report underscores, land financialization, extreme concentration, and corporate opacity are not inevitable. They are the outcomes of deliberate political choices, weak regulation, and a global economic model that puts profit above people and planet. In this context, the upcoming 2026 Second International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD+20) in Colombia offers a vital opportunity to bring redistribution back to the global agenda—firmly rooted in human rights, food sovereignty and global justice.

[1] Lowder S K et al (2021) Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? World Development 142:105455. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105455 [2] Savills (2024) Spotlight: Global Farmland, 26 September 2024. Available at: www.savills.com/research_articles/255800/366736-0 (last accessed 21 August 2025). Savills is one of the leading global real estate services firms based in the UK. Savills’ Global Farmland Index is based on the average value of prime farmland in US Dollars per hectare in 15 key farmland markets: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Spain, United Kingdom, United States and Uruguay [3] Nuveen Natural Capital (2024) Sustainability Report 2024: 11. Available at: www.nuveen.com/global/insights/responsible-investing/2024-natural-capital-sustainability-report (last accessed 21 August 2025). [4] FIAN (2025) Global land grab highlights growing inequality. Available at: https://www.fian.org/en/global-land-grab-highlights-growing-inequality-and-need-for-reform/ (last accessed 22 August 2025). [5] Blue Carbon (2023) www.instagram.com/p/CwCdM9GN_9q; www.instagram.com/p/Cpjkd2frjNk; www.instagram.com/p/CpjkjCPLMPk; www.instagram.com/p/C0UE0WRNomJ; www.instagram.com/p/C0WR2JHJkmX; bluecarbon.ae/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Teaser_Zimbabwe_BC-003.pdf (all last accessed 21 August 2025). [6] Lowe R (2025) Top 40 natural capital investment managers 2025: Fields, forests, fast Real Assets. Available at: https://realassets.ipe.com/special-reports/top-40-natural-capital-investment-managers-2025-fields-forests-fast/10128339.article (last accessed 21 August 2025) [7] CADE (2023) “Anexo 2 - Notificação do Ato de Concentração de Cosan e Nuveen ao Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica (CADE)”, of 12/19/2023, “Parecer Nº 3/2024/CGAA5/SGA1/SG”, Case number 08700.009130/2023-27. For more information on TIAA’s structure, please see Chapter IV. A document from CADE - Brazil’s national competition regulator - for the creation of Radar Gestão de Investimentos S/A, shows that Radar’s properties are currently managed by Nuveen Latin America, a TIAA subsidiary. Please also see: Rede Social de Justiça e Direitos Humanos & Friends of the Earth US.