December 1, 2025

#29 Following the Paths of Assetization: Notes from the Brazilian Agriculture Case

Vanessa Perreira Perin follows the opaque and far-flung pathways of agricultural assetization in Brazil. Identifying two distinct phases of agricultural financialization within the political economy of Brazil, she situates the agricultural asset form within its historical-legal context, highlighting the political battles that have shaped these pathways. This has resulted in an array of intermediaries that shape the transformation of agricultural land into assets.

***

In early June 2025, a new controversy over the tax reform proposals put forward by the incumbent government in Brazil reignited an ongoing conflict between the federal Executive Branch and the National Congress. The focus of the discussions was the implementation of Provisional Measure No. 1,303, which primarily addressed the taxation of certain financial investments and virtual assets in the country. The measure specified, for instance, that online betting companies would be subjected to an 18% tax on their profits, while fintechs would be taxed at rates ranging from 15% to 20%. Likewise, fixed-income securities that were previously exempt from Personal Income Tax would become taxable, including some of the so-called “agribusiness securities,” such as Agribusiness Credit Bills (LCAs) and Agribusiness Receivables Certificates (CRAs), which would be taxed at a 5% rate. As expected, this latter proposal faced widespread opposition from sectors of the financial market, agribusiness-related associations, and their representatives in the National Congress, particularly those gathered at the Agribusiness Parliamentary Front (FPA).

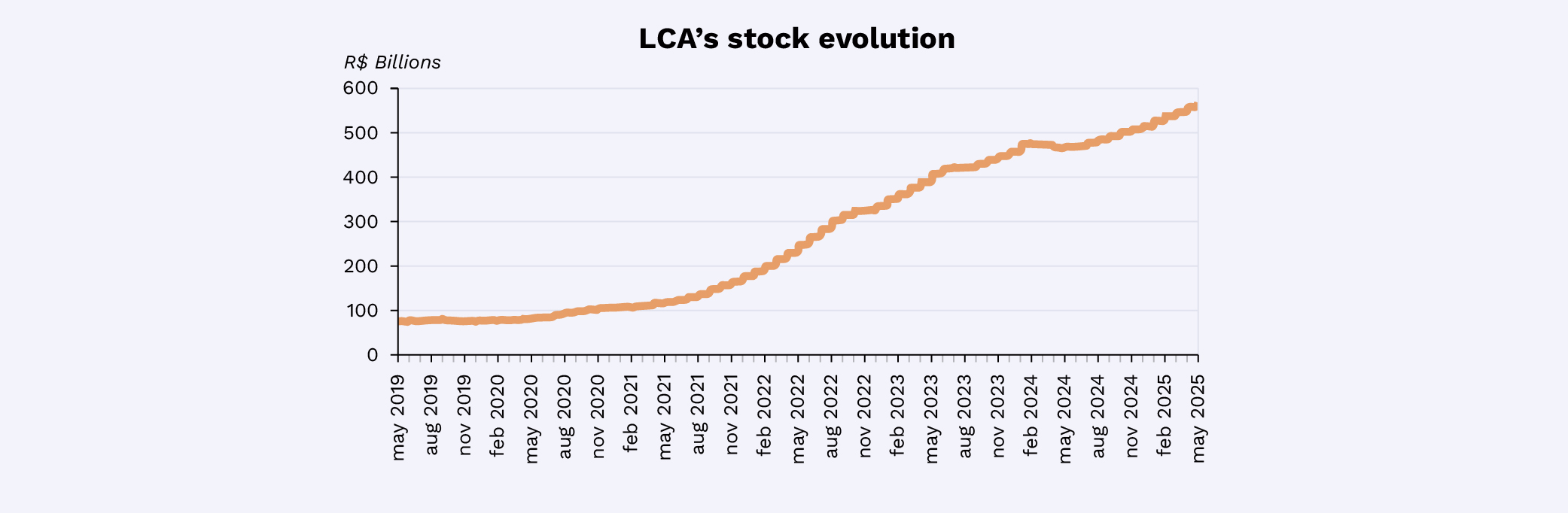

According to the Ministry of Finance, which drafted the Provisional Measure, the proposal aims to revise tax benefits that have caused distortions in Brazil’s tax system. However, the FPA, along with sectoral entities such as the National Confederation of Agriculture, the Brazilian Rural Society, and the Brazilian Agribusiness Association, argues that removing tax exemptions on earnings from LCAs and CRAs could reduce the attractiveness of these financial instruments to investors. They contend this could lead to a decline in rural credit, as LCAs alone account for approximately 43% of private credit in agribusiness and 18% of all rural credit nationwide [1]. While officials of the federal government and some financial analysts argue that the 5% tax rate would have minimal impact, as it remains lower than the rates applied to other types of investments, agribusiness leaders offer a more cautious perspective. They warn that this scenario may result in scarcer and more expensive private credit, which would raise agricultural production costs and ultimately drive up food prices. According to a statement from the Brazilian Agribusiness Association, the measure could “undermine one of the main sources of private financing for one of the largest sectors of the Brazilian economy,” thereby affecting the competitiveness, predictability, and stability of rural producers and agricultural supply chains.

Despite the complex power struggles and lobbying interests behind these positions, this controversy exposes a trend that has grown in Brazilian commercial agriculture over recent decades: its transformation into a new class of financial assets, in other words, its assetization. As Birch and Muniesa [2] highlight, the “asset form” relates to something that can be owned, controlled, and traded as a consistent stream of revenue, typically based on estimates of future earnings discounted in the present. It is important to emphasise that the asset form does not stem from the inherent qualities of what is being capitalised. Assets are created. As with commoditisation processes, their creation involves transforming a good, resource, or service into a standardised and homogeneous product, capable of being exchanged for others through the establishment of equivalent values. Nevertheless, while the production and exchange of a commodity are linked to a specific moment in time [3], the arrangement of a financial asset involves operations aimed at the continuous and consistent generation of revenues. Furthermore, assetization entails a technopolitical process of value creation, centered on developing the material, institutional, technological, legal, and governance conditions that enable the conversion of future earnings into comparable present-day assets [4].

Constructing assets from agriculture, therefore, involves assembling a set of logics, techniques, and tools to establish uniformity and consistency amidst the volatility and “stubbornness” of its materiality [5]. In Brazilian agriculture, especially in corporate farming, the process of assetization began to assume a more structural form following a series of political and economic changes in the 1980s. During the so-called “modernisation of agriculture” period (1965-1980), the sector had extensive access to subsidised public credit. Nevertheless, with hyperinflation and the fiscal crisis the country faced in the 1980s, this model collapsed. From then on, private capital was gradually called upon to play a more significant role in financing agricultural production. The Brazilian state itself began seeking alternative funding sources for the sector, which led to the creation of new credit instruments that facilitated producers’ access to the resources (and logics) of the financial market.

One of the earliest tools that enabled the conversion of agricultural commodities into assets was the “green soybean” contract, which emerged in the mid-1980s and is considered a precursor to modern barter operations. These agreements involved the upfront supply of inputs or the extension of credit to farmers by trading companies, input suppliers, and agricultural retailers, with the debts settled through the delivery of the crop’s harvest. The pivotal moment in the assetization of Brazilian agriculture, however, was the introduction of the Rural Product Bill (CPR), enacted by Law No. 8,929 of 1994, which allowed farmers to sell agricultural commodities before harvest. Similar to green soybean contracts, rural producers could now forecast their income through a government-regulated and banking-endorsed mechanism. Shortly thereafter, Law No. 10,200 of 2001 introduced the financial version of the CPR (CPR Financeira), allowing the trading of agricultural products financially, without the physical transfer of goods. With a straightforward structure providing greater stability and predictability in credit transactions, CPRs were widely adopted and continue to serve as the primary instrument of private financing for Brazilian agriculture. It is notable that, with the introduction of the financial CPR, traded volumes increased significantly as the banking system began acting as a buyer of these securities [6].

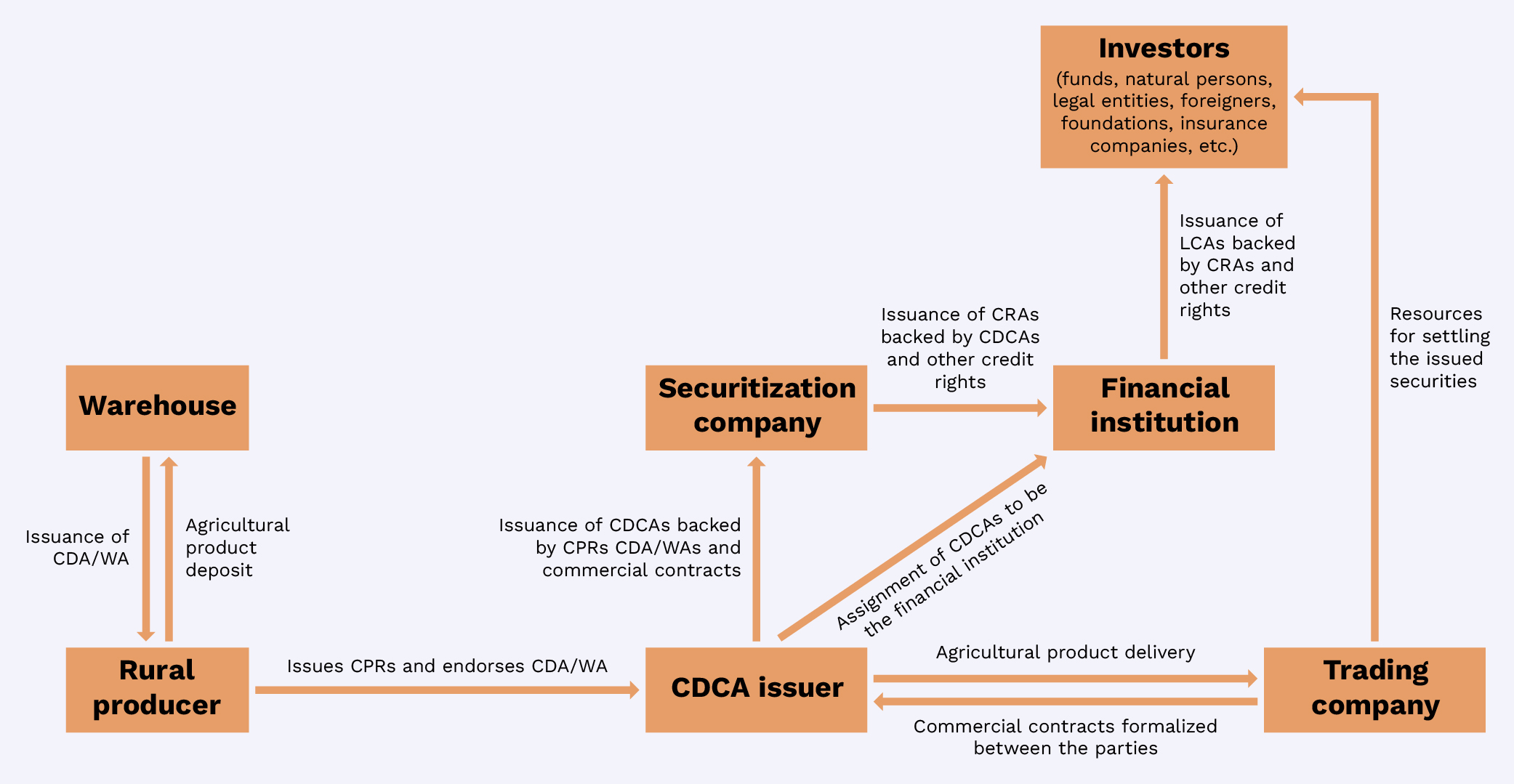

A second crucial phase in the assetization of Brazilian agriculture occurred in the early 2000s, coinciding with the restructuring of rural credit policies and the rise in agricultural commodity prices. Under pressure from agribusiness sectors, which were growing as an influential political and economic force in the country, the Brazilian government introduced the “agribusiness securities”: the Agribusiness Credit Rights Certificate (CDCA), issued by processors and input suppliers; the Agribusiness Credit Bill (LCA), issued by banks; the Agribusiness Receivables Certificate (CRA), issued by securitisation companies; and the Agricultural Deposit Certificate and Agricultural Warrant (CDA/WA), issued by warehouses. This measure addressed the sector’s demand for credit instruments to broaden the involvement of different actors in funding agribusiness, particularly through the capital market. Although CPRs were initially issued solely by farmers and their cooperatives, they began to be used as collateral for new operations involving the latest financing tools. This enabled new sectors of agribusiness to become issuers of financial securities.

(Non-exhaustive) Pathways for the issuance of agribusiness securities. Source: Adapted by the author from CNA (2018) [7]

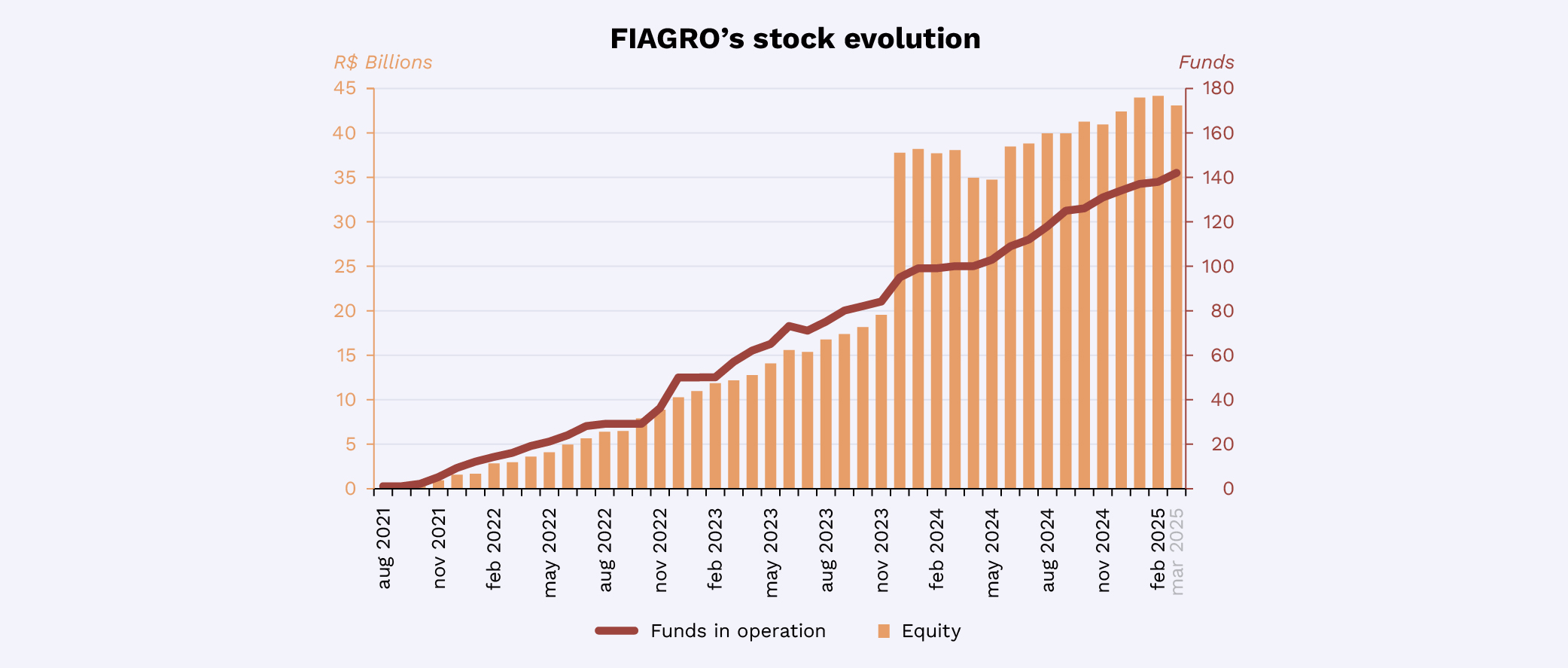

The issuance of agribusiness securities took time to gain momentum. As Caffagni [8] notes, the legislation was still weak and created uncertainties regarding the legal framework of the new credit instruments. It was only from 2018 onwards that the issuance of these securities began to expand, thanks to new regulatory norms aimed at agricultural credit, combined with a brief period of reduction in the country’s base interest rate. Furthermore, former President Bolsonaro’s administration reduced the leverage of resources and investments by public banks, while promoting their supply through the capital market. Even under the current government of Lula da Silva, a former special advisor to the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply (MAPA) stated that agribusiness “no longer fits within the Plano Safra and should be financed through agribusiness securities and national and international investment funds.” [9] It was during this period that the Investment Funds in Agro-industrial Production Chains (FIAGROs) were created, backed by agribusiness securities, rural properties, and equity stakes in rural companies. As shown in the graphs below, similar to agribusiness securities, FIAGROs have experienced notable growth, driven, among other factors, by their income tax exemption:

LCA’s stock evolution. Source: Translated by the author from MAPA (2025) [10]

CRAs’ stock evolution. Source: Translated by the author from MAPA (2025) [10]

FIAGRO’s stock evolution. Source: Translated by the author from MAPA (2025) [10]

Therefore, the controversy over the taxation of agribusiness securities highlights a shift in the very structure of the official agricultural credit program in Brazil, especially as LCAs become a significant component of this policy. Moreover, claiming a possible withdrawal of investors due to lower returns, the debate promoted by the FPA and other agribusiness lobby groups also reveals another phenomenon already ingrained in Brazilian agriculture: its financialization [11].

Such colonisation of official agricultural credit policy by the logics and instruments of the capital market reinforces the shift from “finance for agriculture” to “agriculture for finance” as described by Martin and Clapp [12]. In this vein, the primary motivations for production become more closely tied to the financial returns expected by investors and shareholders. At the same time, fundamental issues, such as the persistent inequality in access to credit between small farmers and large agribusiness companies in Brazil, are sidelined in the background. Furthermore, agribusiness securities are created through financial engineering mechanisms that convert them into asset-backed securities – assets backed by other assets – adding a new layer of assetization. This process thus widens the gap between financial products and the real production of agricultural goods, a core feature of the financialization of agriculture [13]. The increasing number of intermediaries in this debt chain, each motivated by their own interests and often misaligned with the long-term needs of the agricultural sector, is another notable aspect of financialization [14].

The debate over the 5% tax on agribusiness securities, therefore, highlights that the financial market – with its logics, instruments, and actors – is already deeply intertwined with Brazilian agricultural policy. In line with the arguments advanced by Christophers [15] and Ouma [16], these circumstances reinforce the need to politicize the discussion around financialization. In the case of Brazilian agriculture, focusing on the more traceable material dimensions of assetization and the concrete effects it produces may offer a fruitful path forward.

[1] Agro Estadão (2025) SRB e ABAG se posicionam contra tributação das LCAs. Available at: https://agro.estadao.com.br/agropolitica/srb-e-abag-se-posicionam-contra-tributacao-das-lcas (last accessed 05 August 2025) [2] Birch K and Muniesa F (2020) Introduction: Assetization and Technoscientific Capitalism. In Birch K and Muniesa F (eds) Assetization (pp 1–42). The MIT Press. [3] Appadurai A (1986) Introduction: commodities and the politics of value. (1st edition) In Appadurai A (ed) The Social Life of Things (pp 3–63). Cambridge University Press. [4] Birch K (2024) Assetization as a mode of techno-economic governance: Knowledge, education and personal data in the UN’s System of National Accounts. Economy and Society 53(1):15–38. [5] Sippel S R (2023) Tackling land’s ‘stubborn materiality’: the interplay of imaginaries, data and digital technologies within farmland assetization. Agriculture and Human Values 40(3):849–863. [6] In Brazil, converting agriculture into financial assets also involves considering the role of agricultural derivatives trading through commodity futures markets, which started in 1983 with the establishment of the Brazilian Futures Exchange in Rio de Janeiro. However, this market has traditionally been limited to large-scale producers and well-capitalized traders. In contrast, CPRs stand out due to their wider reach, involving a more diverse range of producers. [7] CNA (2018) Guia dos Títulos do Agronegócio. Confederação Brasileira da Agricultura, Brasília. [8] Caffagni L C (2021) O legado do período dos juros baixos. Agroanalyzis, 41(8): 20–23. [9] The Plano Safra is an annual programme by the Brazilian government that consolidates a range of public policies, credit lines, financial incentives, and technical assistance aimed at the agricultural sector. See https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/quem-vai-financiar-o-agro-%C3%A9-setor-privado-diz-assessor-direto/?originalSubdomain=pt. (last accessed 05 August 2025) [10] MAPA (2025) Boletim de Finanças Privadas do Agro. Brasília: Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Available at: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/politica-agricola/boletim-de-financas-privadas-do-agro. (last accessed 05 August 2025) [11] Regarding the financialization of agriculture in Brazil, see: Leite S P (2024) Estado e financeirização da agricultura brasileira: transformações em curso e implicações sociais, políticas e econômicas. In Lavinas L et al. (eds.) Financeirização: crise, estagnação e desigualdade São Paulo: Editora Contracorrente, Balestro M V and Lourenço L C (2014) Notas para uma análise da financeirização do agronegócio: além da volatilidade dos preços das commodities. In Alvez N and Navarro Z (eds.) O mundo rural no Brasil no século 21: a formação de um novo padrão agrário e agrícola. Brasília: Embrapa. [12] Martin S J and Clapp J (2015) Finance for Agriculture or Agriculture for Finance? Journal of Agrarian Change 15(4):549–559. [13] Clapp J (2014) Financialization, Distance and Global Food Politics. Journal of Peasant Studies 41(5):797-814. [14] It is no coincidence, therefore, that the response from the Minister of Agrarian Development to the controversy over the taxation of agribusiness securities was that those who finance their harvests through these instruments belong to the more capitalised export segment and that most of the tax exemptions on these securities only benefit intermediaries. [15] Christophers B (2015) The limits to financialization. Dialogues in Human Geography 5(2):183–200. [16] Ouma S (2018) Opening the black boxes of finance-gone-farming. In Bjørkhaug H et al (eds) The financialization of agri-food systems: contested transformations New York, NY: Routledge.