Case studies

Portfolio farming in New Zealand and Tanzania

Sheep farm, North Island. Source: Ouma 2014.

Sheep farm, North Island. Source: Ouma 2014.

My research features eight case studies from Tanzania and Aotearoa New Zealand.

The case studies presented here represent more than merely an attempt to account for “market heterogeneity” (while against the backdrop that the financial industry is often presented imagined as a homogeneous space). As will become obvious, the type and maturity of liabilities, the degree of control and regulation, shape the kinds of connections that are made and the impact that is produced. Such factors exert pressure on the investment chain. The investment models and financial operations express more than sectoral diversity: They reflect the specific “portfolio needs” of investors, and thus cater to different investment cultures, even though they also follow a more general script of assetization.

(Ouma 2020: 140-142)

Aotearoa New Zealand

Pension funds have long-term liabilities (Case 1):

via an Aotearoa New Zealand dairy-focused asset manager, pension fund’s money, largely from Europe – eventually ends up in more than a dozen or so dairy farms across Aotearoa New Zealand (with solid plans to harvest additional returns from vertically integrating milk production and processing). Dairy had been a popular investment among many Aotearoa New Zealand farmers (and some non-farmers) since the late 1990s. Dairy, often referred to as “white gold” generates relatively predictable income streams that can be capitalized. Some farmers overdid it, however, loading their farms with so much debt in an attempt to leverage returns that they (or their banks) had to make distress sales or calls. The availability of distressed, or sometimes simply undervalued, assets in a market with a bright future seemed like a promising “value play” to many overseas investors, including European pension funds.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 142-145.

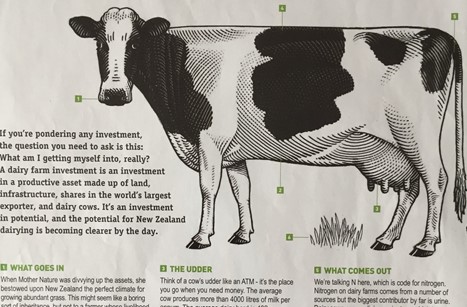

Aotearoa New Zealand and the White gold rush. Source: Ouma 2014.

Aotearoa New Zealand and the White gold rush. Source: Ouma 2014.

Leveraging the family farm (Case 5):

an offspring of a successful farming dynasty in Aotearoa New Zealand rediscovers his farming roots after a successful career in the financial sector, trying to capitalize on investors’ increasing appetite for forestry and agriculture. Combining his knowledge of the financial industry with strong networks in Aotearoa New Zealand, his firm’s funds offer opportunities in forestry, beef, and dairy as well as permanent crops, now catering for more than 20 pension funds, HNWIs and family offices. The MBA farmer’s own family trust money is invested, too. With additional stakes in the agricultural technology business, the asset manager is at the cutting edge when it comes to the digitally mediated monitoring and control of farms “at a distance”.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 140-142.

Dashboard farming. Source: Ouma 2015.

Dashboard farming. Source: Ouma 2015.

A dairy play for deep and less deep pockets alike (Case 7):

a diversified real assets manager from Europe, who caters for both retail and institutional investors. Having launched several agricultural funds that target different geographies and commodities (alongside other funds for “real assets”, such as shipping or infrastructure), the manager is one of the largest capital brokers in Aotearoa New Zealand dairy. Hit by successive slumps in the global dairy market in 2014 and 2015, the terms of one of its funds and the operations on the underlying farms had to be changed. The asset manager subsequently shifted from conventional to organic dairy production on some of its farms. The case is a good example for how market dynamics can mess up the return scheme of investors and asset managers alike, and how strategies of “value creation” may shift during the lifetime of a fund.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 152-155.

Milking carousel of a dairy investment in Southland. Source: Ouma 2014.

Milking carousel of a dairy investment in Southland. Source: Ouma 2014.

Not all agricultural capital placers are foreign (Case 8):

an Aotearoa New Zealand asset manager, whose founders have been pioneers in the syndication of farms in Aotearoa New Zealand, a practice that has become more widespread since the 1990s. First developed to allow enterprising farmers (and non-farmers) with deep pockets to acquire equity stakes in other farms (while sparing them the worry about the management of these, as the company would cater for that), such local intermediaries are now sought-after partners for institutional investors. In the country’s highly professionalized farming sector, foreign and domestic investors alike can rely on these third parties for the management and monitoring of farms.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 156-158.

Ad of a NZ-based asset manager targeting retail investors. Source: Ouma 2014.

Ad of a NZ-based asset manager targeting retail investors. Source: Ouma 2014.

Tanzania

Silicon Valley goes farming (Case 2):

the endowment fund of a super-rich, US-based former tech economy executive, whose managers saw an opportunity to create “impact” in African agriculture. Although they were “first and foremost … seeking to generate superior returns over the long run”, as the managing director once put it in an interview, “[for] appropriate portions of the portfolio” they also looked for “great, long-term businesses that are viable and sustainable, and positively impact the environment and the community in which they operate” (Interview, 2010*). Joining hands with several development finance institutions (and a few high-net-worth individuals, who would provide equity as “patient capital”, as well as less patient debt), the investors injected tens of millions of US dollars into a former state farm in Tanzania’s Southern Highlands. The farm had been successfully pitched as a private equity growth opportunity by a witty foreign businessperson, with just the right networks in Tanzania and global finance alike. It is one of the more daring schemes of assetization featured in this book – a flipped “undervalued” state farm whose history goes way back into the socialist era. The farm never turned financial asset as planned, as it eventually went into receivership due to production and marketing problems and was sold to the Tanzanian government in 2021.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 145-148.

Producing an irrigated mega-grain farm in Central Tanzania. Source: Ouma 2014.

Producing an irrigated mega-grain farm in Central Tanzania. Source: Ouma 2014.

The delegated fund mandate (Case 3):

a mutual fund of over US$100 million of the wealth management arm of a large European bank, launched in 2007, servicing the needs of investors with less deep pockets. Managed by an external asset manager based in Asia (but staffed with some former employees of the bank), and seeking “value for investors in emerging markets”, the fund has acquired majority stakes in agricultural operations in several countries of the Global South, including a 3,845- hectare grain- farming operation in northern Tanzania. The capital placement on the slopes of Mt Kilimanjaro was made in a region once favoured for its agricultural potential by colonial settlers, Germans and British alike. The new investors were fortunate in that the previous co-owner of the farm was seeking some high-risk-taking equity partners who would help him realize his growth vision in an environment in which local debt was (and still is) notoriously expensive.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 138-140.

A mutual fund’s grain farm. Source: Ouma 2013.

A mutual fund’s grain farm. Source: Ouma 2013.

The impact-oriented family office (Case 4):

an impact-oriented family office from Europe, which targets promising medium-sized enterprises, including agricultural ones, across east Africa. Since dairy processing represents a promising growth opportunity in the region, the office acquired a considerable equity stake in a dairy processor co-owned by the smallholder cooperative supplying the facility. It is the only case sampled here that is a more classic private equity story, whereby “private equity firms acquire small and midsize companies that typically want to grow, but do not have enough capacity, resources to shift to a qualitatively different level of size or competitiveness” (Appelbaum & Batt 2014: 139 [1]). It is also a reminder of the fact that the “agri-investment space” is not just about production but also about pre- and post- farm- gate appropriations of value.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 150-152.

[1] Appelbaum E and Batt R (2014) Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

The farm of a cooperative member supplying the dairy investment. Source: Ouma 2022.

The farm of a cooperative member supplying the dairy investment. Source: Ouma 2022.

Disrupting the Tanzanian poultry sector, carefully (Case 6):

a multi-farm asset that is part of an Africa- themed agricultural fund of over US$100 million managed from Europe, backed by European pension funds, HNWIs and development finance institutions. The asset manager, founded by a well-connected white businessman from southern Africa, and its investors wanted to capitalize on the growing Tanzanian poultry market, which they found to be underserved with “modern” broiler chicken and high-protein animal feed. The capital placement aims at building a “first-class”, vertically integrated industrial operation that links feed production with the raising of day-old chicks later sold on to local farmers. Small in comparison with industrial poultry production in the Global North, or even emerging economies such as Thailand or South Africa, it is nevertheless unmatched in scale in Tanzania.

If you want to read more about this case, see Ouma 2020: 149-150.

A multi-million dollar investment in Central Tanzania: Vertical integration in the making? Source: Ouma 2017.

A multi-million dollar investment in Central Tanzania: Vertical integration in the making? Source: Ouma 2017.