Grounding assetization

Between world history and ethnography

What specific processes, relations and practices produce institutional landscapes in (and beyond) agriculture? How do the logics of financial value extraction become grounded in particular places? How exactly is a farming venture turned into a financial asset?

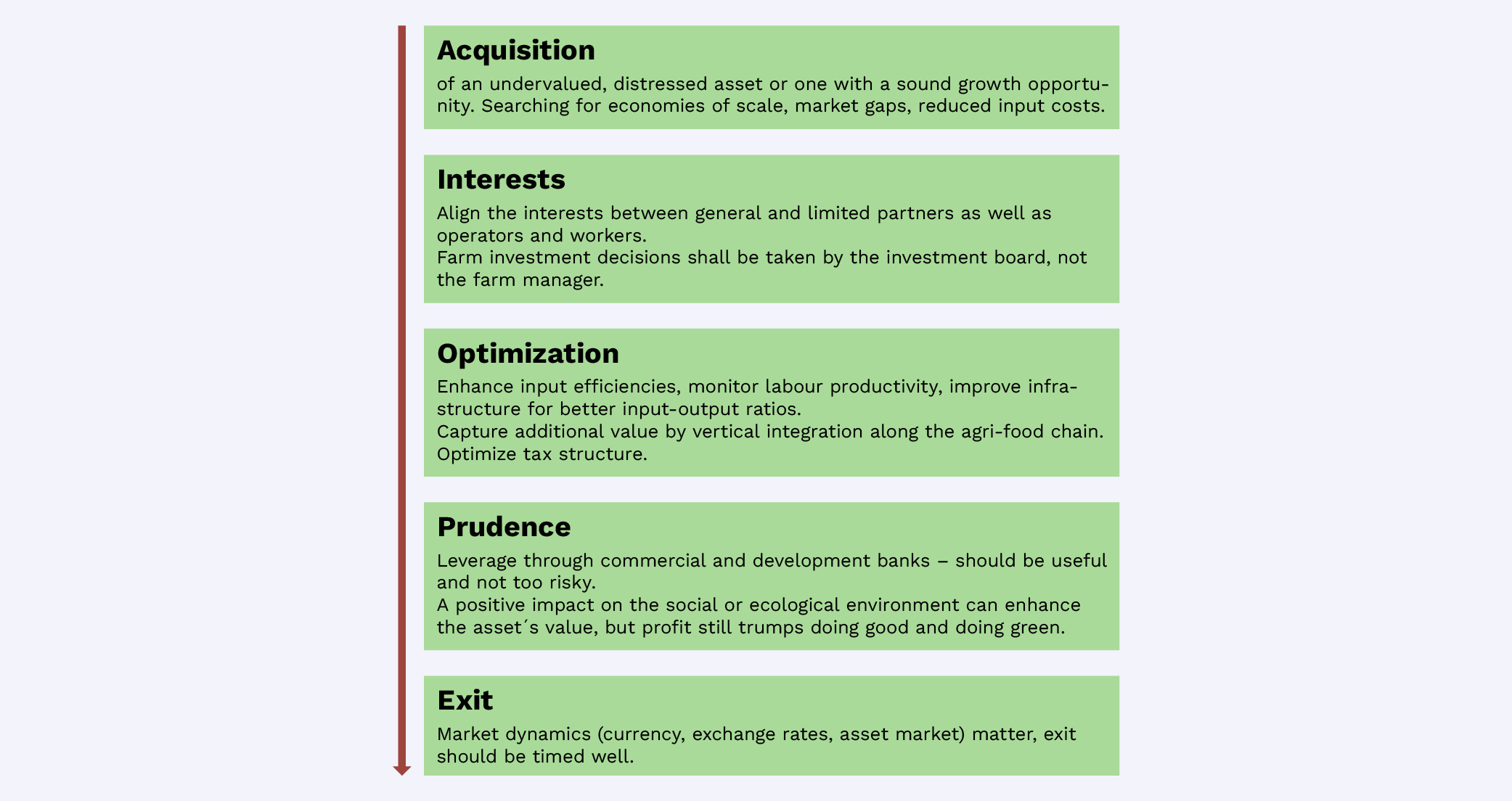

Steps in agricultural assetization. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 138.

The financial worth of agricultural assets is partly produced through commodity output and thus dependent on generating material things (practices of arbitrage, asset price appreciation and gains from leveraging external debt can add further value). How this process of assetization unfolds in practice is further illustrated by the case studies sampled by the research featured on this website.

(Ouma 2020: 137)

Doing research. Source: Ouma 2013 (left) and 2014 (right).

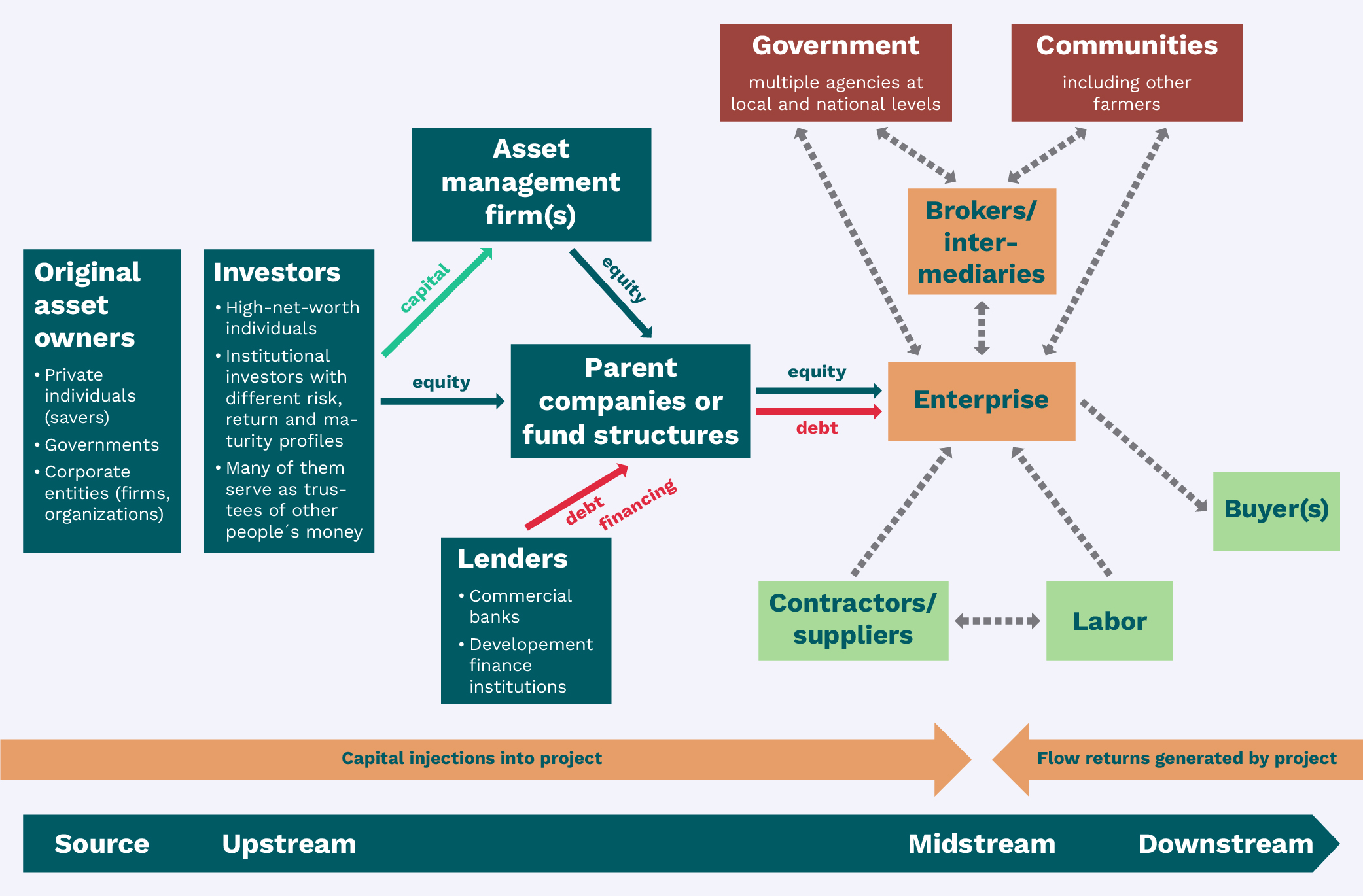

Doing research. Source: Ouma 2013 (left) and 2014 (right). The assetization of farming ventures happens through spatially extensive investment chains. To trace these chains, I did multi-sited research across five continents, and I took part in investment conferences and meetings of asset managers, where agriculture as an asset class is consolidated through narratives and numbers.

Furthermore, the research takes us to the agricultural assets themselves and their surrounding communities in Tanzania and Aotearoa New Zealand, as well as to the offices of various intermediaries: investment consultants, lawyers, market intelligence providers. And we will encounter sites of resistance, where finance-driven investments in agriculture are being criticized and alternative visions of agriculture are being created.

(Ouma 2020: 6-8)

The agri-investment chain and its share- and stakeholders. Adapted from Cotula and Blackmore (2014: 2). Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 7.

The agri-investment chain and its share- and stakeholders. Adapted from Cotula and Blackmore (2014: 2). Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 7. Socio-spatial extensiveness often also means organized socio-spatial complexity, or, worse, opacity. Both pose a challenge to regulators (as well as to researchers). But by identifying and grounding agri-investment chains and their underlying actor constellations, different “pressure points” (Cotula & Blackmore 2014: 3 [1]) can be identified to repoliticize money flows into the countryside.

The public and academic perception that most of the financialization of farming is taking place in countries of the Global South is at odds with reality: In fact, most of the financial capital placements in agriculture have primarily gone to Aotearoa New Zealand, the US, Canada, Eastern Europe, and Australia, with Brazil and partly South Africa being main southern exceptions.

Despite a whole range of possible “asset trajectories” shaped by a range of national (e.g., property and investment regimes), local (e.g., local agrarian relations; place-based asset histories) and transnational factors (e.g., source of capital), the case studies examined in detail for this project (see here), and the additional analysis of the global agricultural investment space, suggest a more general script of “assetization” and “value creation”. As a practical operation, the “value creation” processes that tie M and M’ together, embedded into far-reaching and future-oriented contractual relationships, rest on establishing specific territories of financial economization, carved out from the “web of life” [2], and heavily policed thereafter. It is through such territories that “the raid of the future on the rest of time” (Vogl 2015: 3 [3]) is organized, an endeavour that faces all kinds of drawbacks and breakdowns, and sometimes fails altogether, as the case of a bankrupt grain investment in Tanzania shows.

[1] Cotula L and Blackmore E (2014) Understanding Agricultural Investment Chains: Lessons to Improve Governance. Rome: FAO.

[2] Patel R and Moore JW (2017) A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[3] Vogl J (2015) The Specter of Capital. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

It is also a process by which asset managers, depending on the ultimate source of capital and the terms of its administration, may end up balancing the need to generate returns for investors with demands from other local, national or transnational players. In the better cases, this can result in more long-term and economically impactful development trajectories, as the cases of the intergenerational investor in Aotearoa New Zealand and the family office investing in Tanzanian dairy have shown, but often short-termism, the imperative to scale up quickly (and opt for scalable production systems in the very first place) and the uncertainties related to what happens to an “asset” after the exit cast shadows over the value generation process.

It should go without saying that the geographical settings discussed here in detail were peculiar for their historical and institutional context, which sets certain limits to how aggressively investors could extract value from agriculture. Examples from other world regions abound, where financial extraction seems to have been much more harmful in environmental or social terms, often – but not only – related to the more clandestine nature of the capital flows involved.

(Ouma 2020: 6-8)