Investment structures

Managing other peoples’ money

Assetization inside and outside agriculture often happens through spatially extensive investment chains involving many players. As expressions of the fact that the original sources of capital (e.g. depositing employees) are often linked via delegation structures with other intermediaries such as pension funds or asset managers, these connect different actors, histories, institutional contexts, and material realities with each other and often cut through different legal systems. By combining risk-return-effective geographic localizations and specific extraction strategies, global investment chains become arenas for the redistribution of value, besides becoming the enablers of new, sometimes global, commodity chains. We can trace their making, the actors involved, the links they establish, and the glue that underpins these.

The "deal cycle" in general

Marx’s description of the reproduction of money. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 113.

Marx’s description of the reproduction of money. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 113. How does capital, managed on behalf of others, multiply? In the world of asset management, it all starts with the deal cycle. The deal cycle describes the transformation of money (M) via the production of commodities (C) and through the workings of other “drivers of value”, into more money (M’). However, rather than taking M’ for granted as a state of affairs, we should treat it as an empirical question: How is money, via the production of agricultural commodities and the addition of external debt, converted into more money from which investors carve out dividends, interest, income (including fees), and capital gains? This is an important question as agri-investments are often deemed mere speculation and rentierism by critical observers. Asset appreciation may happen because of the increasing demand for land, but likewise, such assets need to be worked upon and commodities need to be produced via them.

Before going into the specificities of agri-investment deals, it should be taken into account that the so-called agri-investment space is not homogenous, especially if investments into soft commodities (e.g., via commodity futures) or AG-tech focused venture capital are considered. Nevertheless, most investments in farmland and agricultural production stick to a variation of the private equity model.

(Ouma 2020: 113)

Inside the investment calculus

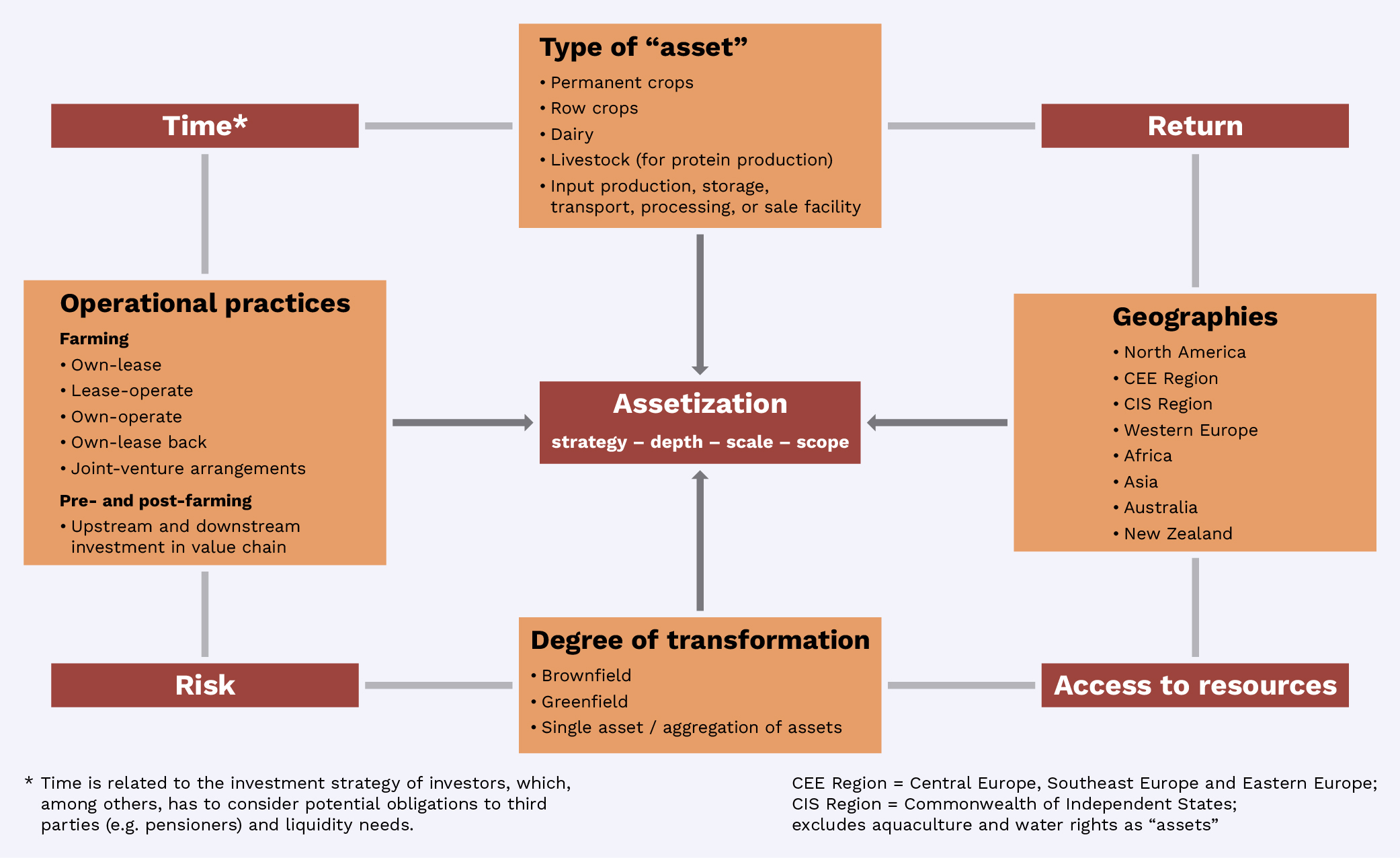

A stylized chart of how agri-focused asset managers make investment decisions. Redrawn from Ouma 2020: 116

A stylized chart of how agri-focused asset managers make investment decisions. Redrawn from Ouma 2020: 116 Before we get to the investment deal cycle itself, we need to understand how assetization decisions are made. How this process unfolds depends on a range of factors. Investors and delegated asset managers calculate their actions in a frame marked by four pillars: time, risk, returns, and access to “resources”. Concerning the latter, both players take into account factors such as the availability, location, and structure of land; soil, climatic and macroeconomic conditions; property and investment regimes; the quality of regional infrastructure; and the distance to and size of commodity markets. The configuration of these pillars, embedded into the interaction of investors with potential intermediaries such as asset management firms, results in different operational strategies, types of assets, investment geographies, and agricultural enterprise structures.

Although this represents a highly stylized and rationalized account that sidelines issues such as gut feelings, herding behaviour, ignorance and lack of expertise (many investors are guided by investment consultants rather than being “AG investment experts” themselves), it nevertheless captures some of the key aspects of the assetization process. How money managers relate to these factors ultimately conditions the strategy and depth of – along with the scale of and scope for – the assetization of farming. For instance, thanks to the availability of skilled farmland operators, many investors/asset managers in the United States opt for an own/lease-back (also known as own/lease out) approach, where farmland is bought and leased out to farmers. This yields stable but low returns. If investors/asset managers are willing to take higher risks for the sake of higher returns, they adopt an own/operate approach.

For instance, all agricultural capital placement scrutinized for the website (and the book) in Aotearoa New Zealand followed such a pathway, even though the asset managers involved would employ farm managers or farm managing equity partners to run the farms acquired. In other regions, such as many parts of Africa, where foreigners cannot own land on a freehold basis, investors/ asset managers actually lease land and operate it themselves.

(Ouma 2022_ 116-117)

Private Equity model ("own-operate")

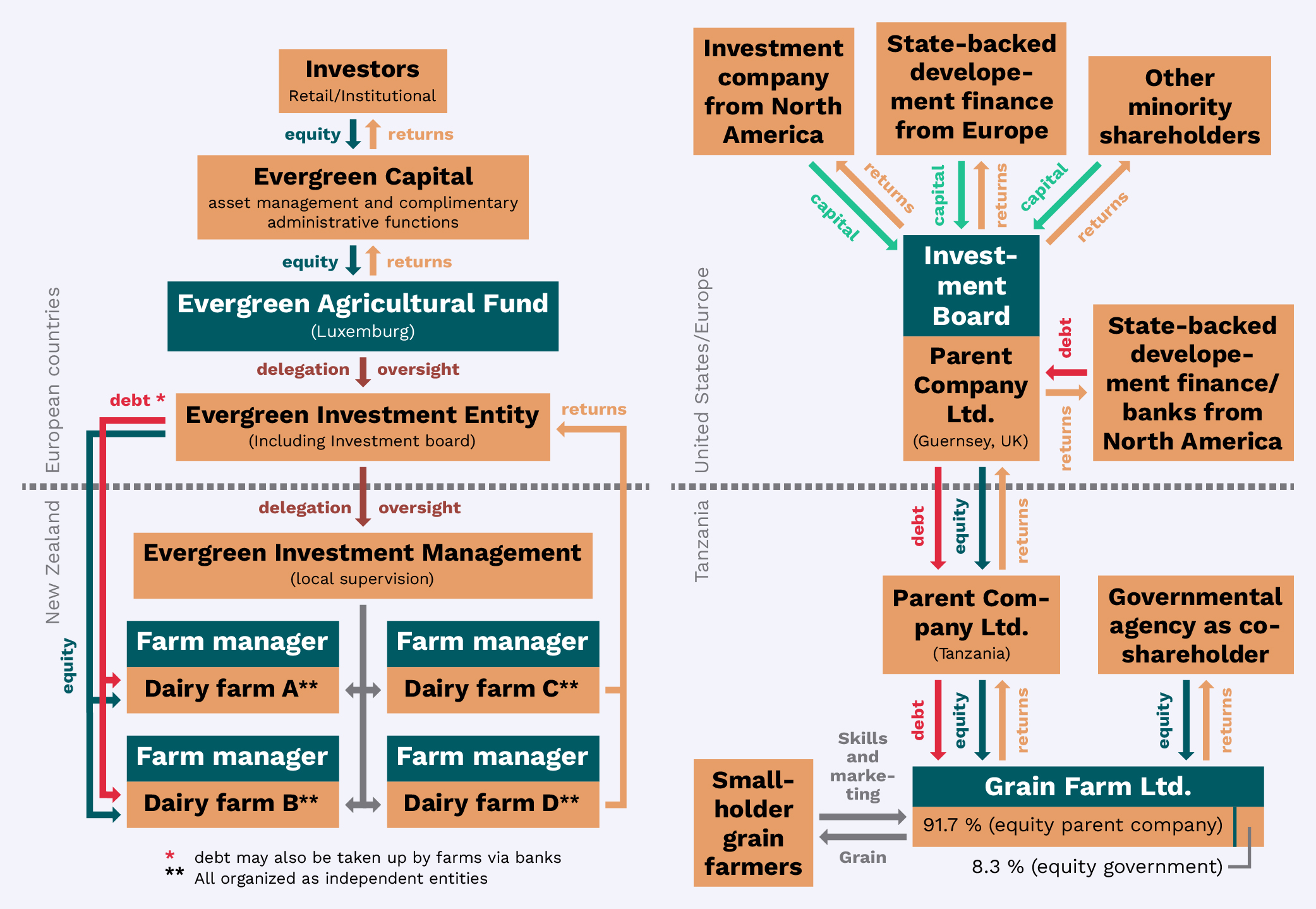

Two investment chains based on private equity models (left side: Aotearoa New Zealand, right side: Tanzania). Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 123.

Two investment chains based on private equity models (left side: Aotearoa New Zealand, right side: Tanzania). Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 123. All investments that I screened through field and research work use variants of the private equity model as investment structures. Via this model, such as pension funds become limited partners (LPs), linked to a general partner (GP), an asset management firm with a specialist agricultural investment expert to whom they entrust their funds. Unlike an ordinary partnership, the limited partnership guarantees less liability for the investors – limited to the value of the LP’s capital contributions. The GP makes all decisions about which ventures to purchase and how to manage them, since it is often taking a majority share, as well as how to exit the investment. The LP is having little direct influence in these processes. If parts of the LP’s invested capital remain untouched, it is to be returned by the GP at the end of an investment period.

Usually, LPs invest more than US$1 million for a given period, however, smaller sums are possible, especially when it comes to retail investors. In order to align the shareholders’ interests, the managers of GPs are often investing their own capital, too. The shareholder value doctrine may also take effect at the level of the farming venture. For instance, hired farm managers may receive bonuses for reaching targets or become equity partners themselves. These strategies also serve as an alignment of interests.

The above-explained private equity model in the form of a limited partnership is often tied to a fund structure, but not necessarily. Other types of investment structures can be private holding and investment companies. For instance, in Tanzania, the limited partnership is legally not established and thus investors have to use non-fund-based models, such as a private holding structure. Yet, the cultural values of PE are equally influential in such cases since the investment idea remains basically identical: an investor acquires an (undervalued) asset, unlocks value by generating an income stream, and then sells it at a higher price in the not-too-distant future. Aotearoa New Zealand introduced the limited partnership model in 2008, following the global investment standard trend.

(Ouma 2020: 120ff.)

The own-lease out model

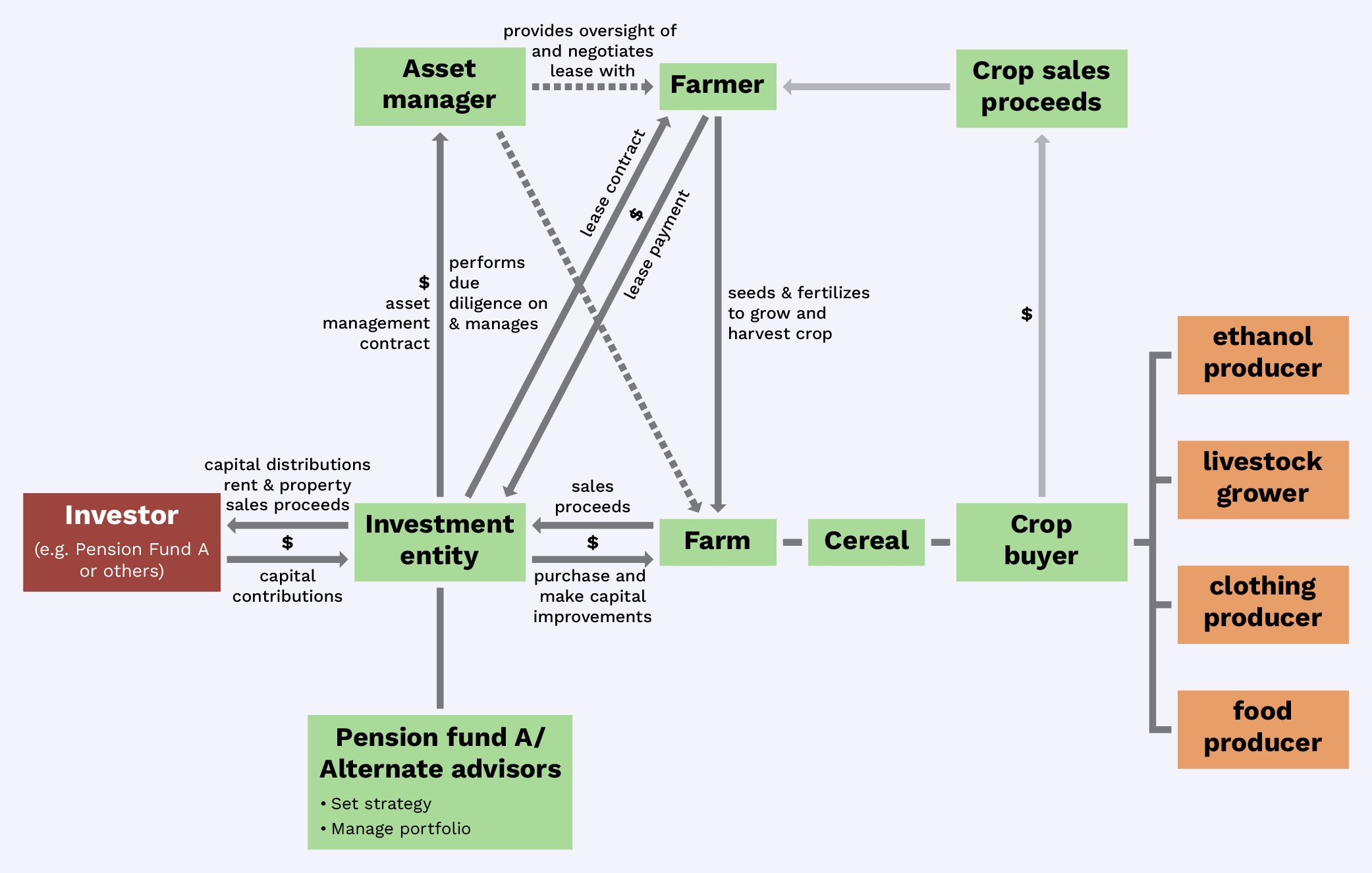

Anonymized organizational chart of the investment of a large US pension fund (own-lease model). Redrawn from collected data.

Anonymized organizational chart of the investment of a large US pension fund (own-lease model). Redrawn from collected data. The investment vehicles in use provide different ‘exposures’ to farmland/agriculture, which is a function of the depth of investment (direct/indirect), the risk-return calculations of investors, the depth of property rights, the liquidity needs of capital invested, and the envisioned mode of exit. Different investment vehicles also result in different pathways of, and scopes for, assetization, express the specific ‘portfolio needs’ of investors, and cater to different investment cultures. Overall, liability issues are of considerable concern. The private equity-based own-operate model is not the only model around! While not studied in detail for this project, investors and asset managers have also resorted to an own-lease-out approach, which is presented here in anonymized form, redrawn from an actually-existing investment case from North America.

Regardless of the investment model adopted, throughout the assetization process, the relations between investors, asset managers, and investee farms are facilitated by a range of additional intermediaries. Besides placement agents, these include industry intelligence providers; consultants who provide due diligence services at the beginning of investment cycles; independent valuers who provide regular valuation services to establish the worth of invested assets; and law firms providing advice on deal structuration as well as on contract corporate governance, remuneration, tax, and investment law

The agri-investment deal cycle

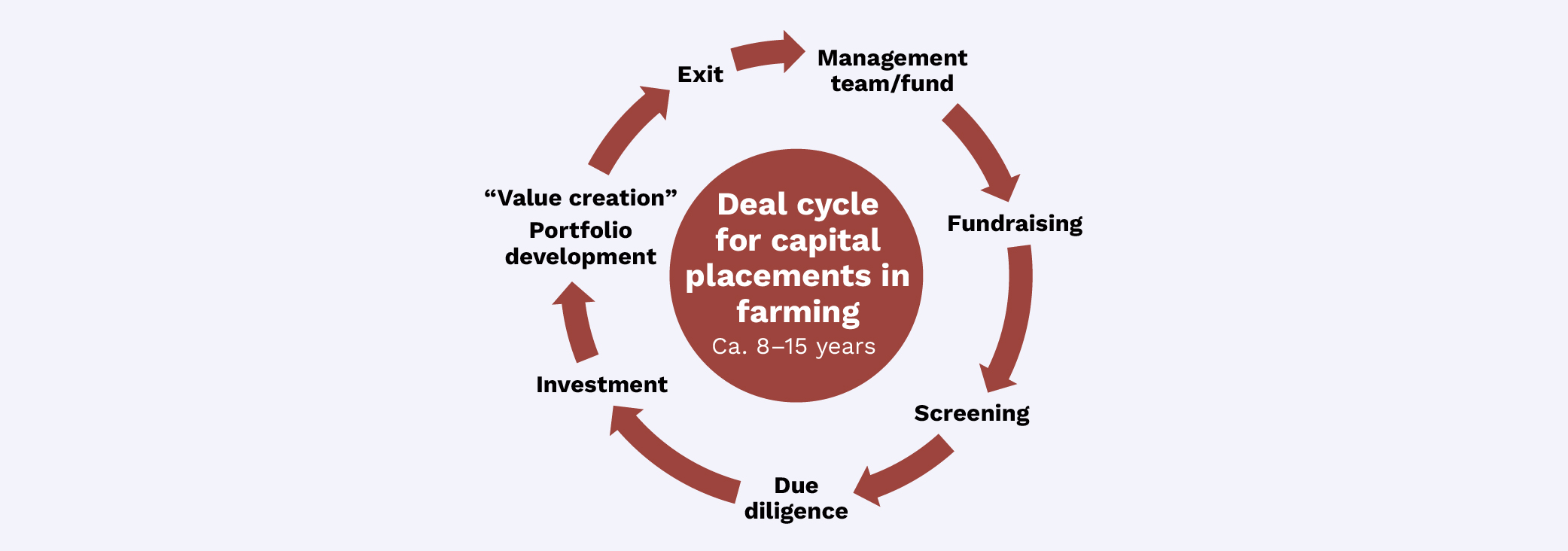

The deal cycle in farming. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 124.

The deal cycle in farming. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 124. When it comes to the actual implementation of the PE model, the starting point of investments in agriculture is often the decision of an investor’s management board to invest funds on behalf of the original asset holders (e.g., pensioners in case of a pension fund) into an agricultural investment fund or farming venture. The GPs mediating the deal may shop around for a while to collect capital from other investors before the fundraising is closed. After this, GPs screen potential projects and assess whether the asset fits into their portfolio. If the investment project seems sound, GPs perform a detailed due diligence analysis, using on-site visits and other means of gathering intelligence. Only then the “real” investment takes place, often via a mixture of injecting both equity and (often external) debt capital. Each step is approved by the investment committee, in which LPs sometimes are represented. The investment is being monitored and its progress is reported on a regular basis. Depending on the long-time planning, the investors will eventually exit the investment (more on exit opportunities, see below). Through various forms of capital injection and transformative undertakings, combined with asset price appreciation and other drivers of value” (e.g., exploiting currency differentials between buying and selling prices), investors seek to “unlock” value.

The investment deal cycle in farming can take 8 to 15 years, depending among other things on the time spent for fundraising (however, there are also investment plays which tout themselves to be “evergreen”, taking a more long-term view of agri-investment). Sometimes, fund managers already have assets at hand even before they start fundraising, and then try to pitch them to LPs as “investment plays”. Access to farmland is often gained through personal contacts, e.g., via investment board members who have good connections into the world of farming.

Most capital placements in farms are growth plays which means that either a greenfield (plain (farm)land without facilities and infrastructure) or brownfield (farmland with existing facilities, e.g., an indebted but otherwise developed farm) asset is being bought, improved, and later sold. Brownfield investment can also include the aggregation of several smaller farms into larger units in terms of economies of scale, as well as capital placements in agricultural processing operations. Contrary to the public image of capital placements in agricultural production, these usually do not involve “asset stripping”, as known from other PE domains [1].

(Ouma 2020: 124-127)

[1] Burch D and Lawrence G (2013) Financialization in agri-food supply chains: private equity and the transformation of the retail sector. Agriculture and Human Values 30 (2): 247–58.

Exit opportunities

The deal cycle is closed with the so-called exit. Investors do not stay around forever. One day, the future envisaged has to be capitalized. Despite the importance of the exit as a key moment in the deal cycle, it is difficult to come to terms with its operational details, since many of the agricultural investment schemes have not reached the exit date (or asset managers have been tight-lipped about the performance of their assets under management). As interviews revealed, the people working on the ground, even senior managers, often have no exact knowledge of what the money managers in the background have planned for the business. The standard narrative at the beginning of the agricultural investment boom was that assetized farming ventures would be rolled over into another fund, sold to other institutional investors or agrobusiness companies (trade sales), or made available to the public through the stock listing (initial public offering: IPO). One asset manager drew a completely different picture of what was often the most practical solution, however:

“So, the standard exit is the sale to farmers. At least 98 percent of the world’s agricultural sector is still run by farmers. In other words, by family farms, with varying equity resources, but in some cases very wealthy families. This means that the situation would be fatal if you had to rely on any trade sale or IPO or any financial engineering variant at the exit. Especially, one should plan in such a way that one can sell individual farms to individual farmers – what we have always done so far. Which doesn’t mean you can’t get a bundle. But that shouldn’t be the strategy from the beginning. So, the existing cases show that big investors, who are on the move with 100, 120 million tickets for their farm clusters, in Brazil or wherever, they’ve been trying to sell those for four years because the target group for such large parcels is so small that it’s highly dangerous” (Interview, 2014).

Based on the above, his own firm opted for dairy farming systems that are scalable into different modules, which allowed his firm to slice farm sales according to the appetite of incoming investors.

In some regions, such as many parts of Africa, public selling strategies (“underdeveloped” stock markets!) and resale to farmers are both unlikely options (there are few local farmers with such deep pockets!). In such environments, trade sales may be more likely. Investors dream of capitalizing on the fact that food-importing governments, food-processing companies, commodity traders and/ or supermarkets are increasingly concerned about securing their supply chains but want to avoid the risk of entering into primary production directly, or, at least, try avoiding entering such “frontier markets” as first-mover investors.

Choosing the right moment to exit one’s investment means taking currency issues as well as demand-related site issues into account. The latter means to monitor potential buyers for the assetized venture. Currency issues matter if the fund is listed in one currency whereas the expenses as well as the asset purchase are listed in another. Most cases that I studied in detail had not yet come to an exit. A rather well-known exit, from the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board in 2017 out of US$250 million US farmland investments, occurred not only due to Board decisions, but supposedly was also driven by public pressure. What is the influence of public pressure? More on this here.

(Ouma 2020: 127-130)