Data troubles

The politics of numbers

It is one thing to have aggregated data about macro-trends in the agricultural investment space, and another to accurately know who is buying up farmland and stakes in agricultural companies in specific places, on which terms and through which kinds of relationships. Although the macro-data presented on this website stems from players with privileged access to the agri-focused world of money management, exploring the world of agricultural investment can quickly turn into an empirical nightmare.

(Ouma 2020: 66)

When investigating institutional landscapes in agriculture, the opacity of land markets meets the opacity of global finance. Contemporary agricultural investments are often channelled through far-flung chains of delegation cross-cutting several jurisdictions, including ones of secrecy; are protected by non-disclosure agreements or hidden from the public because the channels used (for example, private equity structures) are not listed publicly and are therefore exempt from legal requirements, such as annual public reports; or cannot be easily separated from ordinary (so-called “strategic”) agribusiness investments. Furthermore, in many countries of the Global South there is an insufficient level of reporting, and even institutions of the same state may report different figures due to vested interests or a lack of coordination. Moreover, asset managers or companies looking for future investors may inflate numbers, making their investments larger than they actually are. The popular data bank Land Matrix, a leading source on global farmland investments, does not adequately represent agricultural investments in broader terms and is biased towards the Global South, even though much of the agri-finance buzz is found in countries in the Global North. Sources that might shed some light on these trends, such as investment conferences, specialist industry intelligence, or expert opinions, are obstructed by certain entry barriers, which need to be grappled with by any research into finance. Some of that intel can be bought at a dear price.

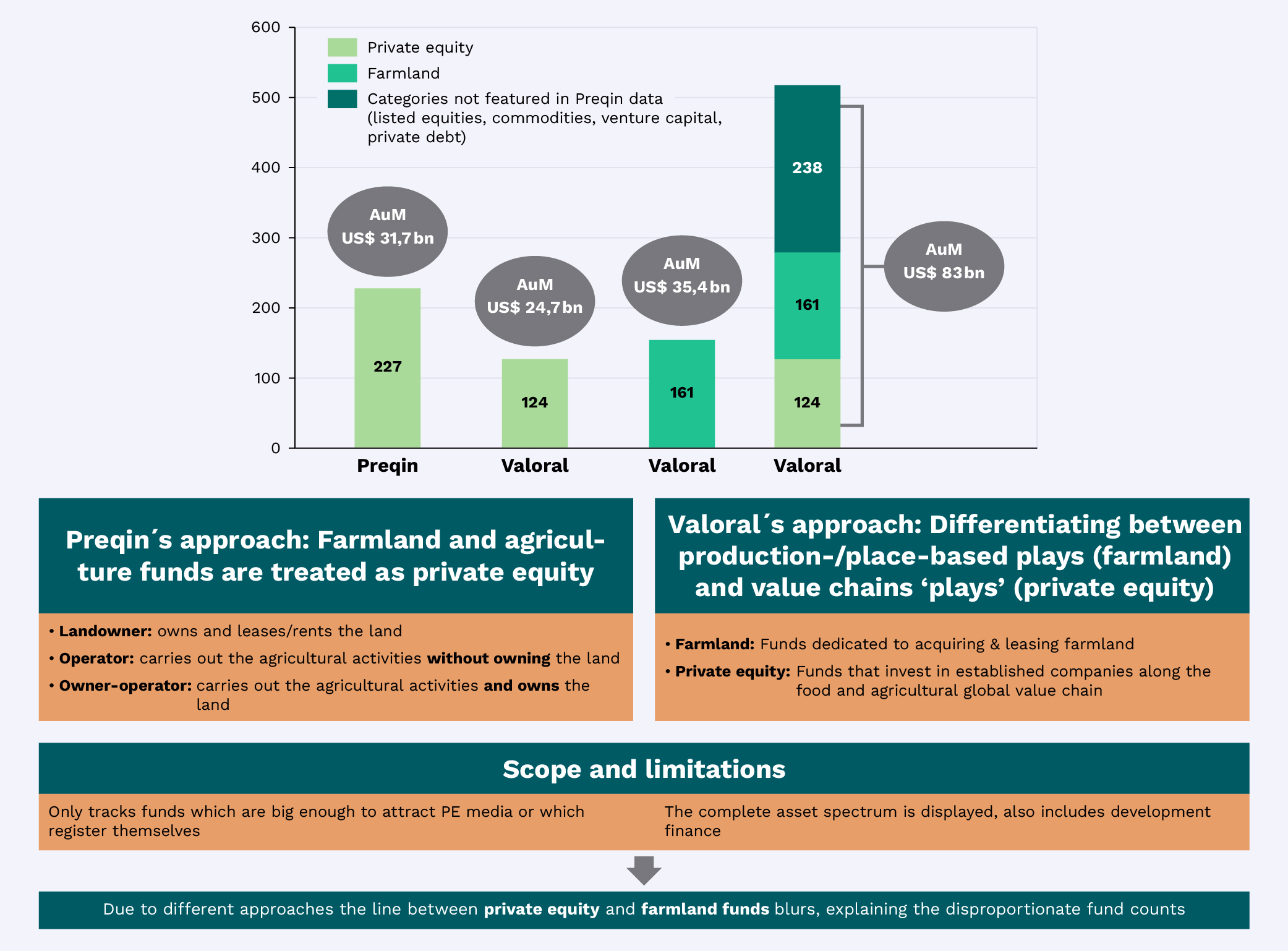

Costly data collected by agri-finance intelligence service providers can differ according to the frame of analysis and the investment focus. For instance, the three leading providers in the agri-finance space – Preqin, Agri-Investor, and Valoral Advisors – provide significantly different numbers on the rise in finance-driven agricultural investments over the past 15 years. This is due to different approaches: As you can see in the figure below, whereas Preqin treats farmland and agriculture funds as private equity, Valoral differentiates between production-/place-based plays (such as farmland) and value chain ‘plays’ (such as private equity). This leads to a blurred line between private equity and farmland funds and explains the disproportionate fund counts of various data banks.

Comparison of two leading sources of agri-finance market intelligence. Source: Based on data provided by Valoral Advisors (2018)[1] and Preqin (2018)[2].

Comparison of two leading sources of agri-finance market intelligence. Source: Based on data provided by Valoral Advisors (2018)[1] and Preqin (2018)[2]. [1] Valoral Advisors (2018) Breakdown of investment funds included in Valoral Advisors’ database (by investment target, region and fund’s status: proprietary data bank). Luxembourg City: Valoral Advisors. [2] Preqin (2018) 2018 Preqin Global Natural Resources Report. London: Preqin.

The many entry points for finance in global food and agriculture asset classes. Source: Redrawn from Valoral Advisors (2018: 13). [1]

The many entry points for finance in global food and agriculture asset classes. Source: Redrawn from Valoral Advisors (2018: 13). [1] A few more issues are complicating the analysis: Should we include timber, water rights or aquaculture into the picture? Do the statistics capture complex ownership patterns among agricultural ventures? Do we focus on funds whose primary strategy is farmland – or do we include those with agriculture as one investment among many?

In what follows, we present a few data snapshots on developments from a global perspective, mainly drawing on the data of private agri-intelligence firm Valoral Advisors and complementing this with other data when applicable. Valoral Advisors data represents the most comprehensive information in the intelligence space, going back to the mid-2000s, when agri– finance was mainly about listed equities, commodities, and a few farmland vehicles, with very little involvement by institutional investors. This also helps decentre the existing focus on farmland, showing that finance has many entry points for penetrating the world of farming.

[1] Valoral Advisors (2018) Breakdown of investment funds included in Valoral Advisors’ database (by investment target, region and fund’s status: proprietary data bank). Luxembourg City: Valoral Advisors.

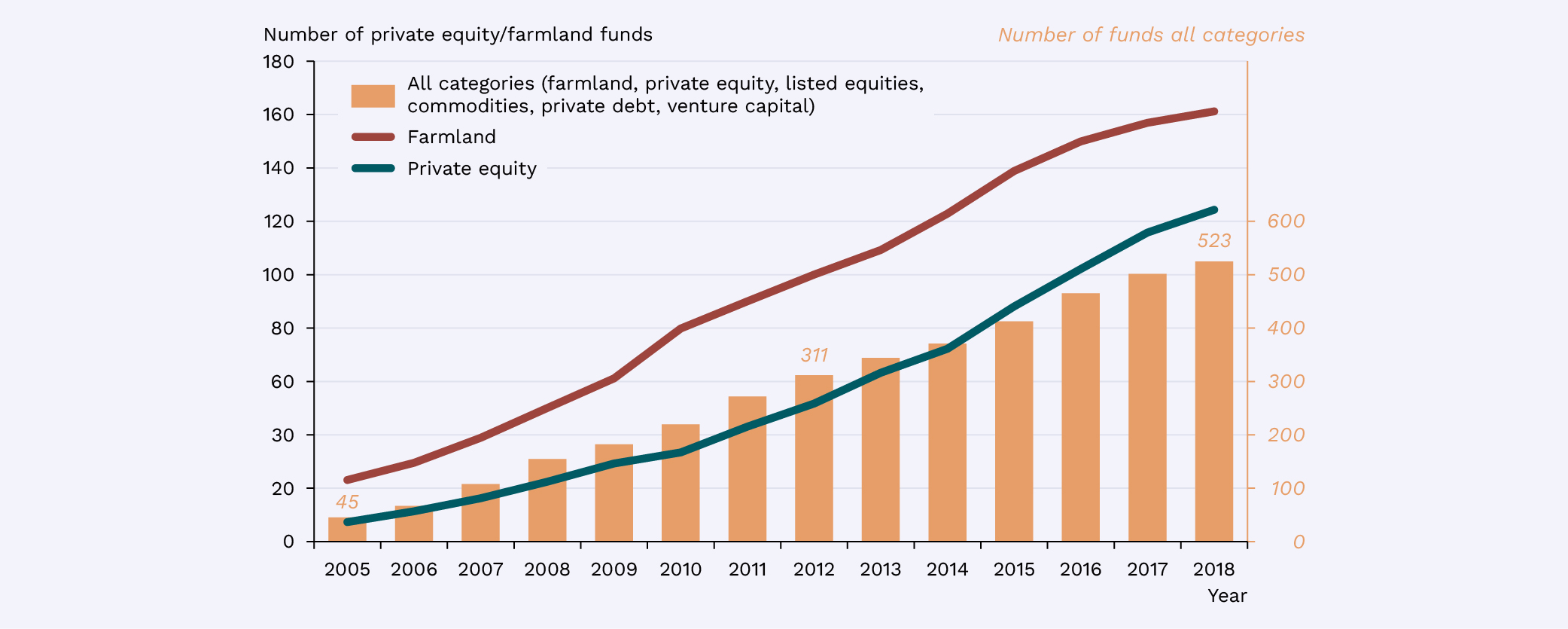

As the figure below shows, the world has seen a sharp increase in agricultural investments in both “mature” and “emerging” markets since at least 2005, the earliest year for which such data is available. According to the broader view on the food and agriculture asset class, the number of agricultural funds rose from 45 (with 23 farmland-focused), to 523 by the second quarter of 2018 (with 161 of these funds having direct exposure to farmland and 124 being more classic private equity plays), plus another 35 under formation. By that time some US$83 billion had been invested in food and agricultural funds or other types of institutional platforms. Although a high number, this was only about half the size of all global timber investments at that time, and a tiny fraction of the US$533 billion invested in natural resources in 2017 (this also represented a tiny 0.3% of global AUM as of 2016).

Evolution of investment funds specialized in food and agricultural assets, 2005 to 2018. Source: Drawn based on data provided by Valoral Advisors (2018). [1]

Evolution of investment funds specialized in food and agricultural assets, 2005 to 2018. Source: Drawn based on data provided by Valoral Advisors (2018). [1] [1] Valoral Advisors (2018) Breakdown of investment funds included in Valoral Advisors’ database (by investment target, region and fund’s status: proprietary data bank). Luxembourg City: Valoral Advisors.

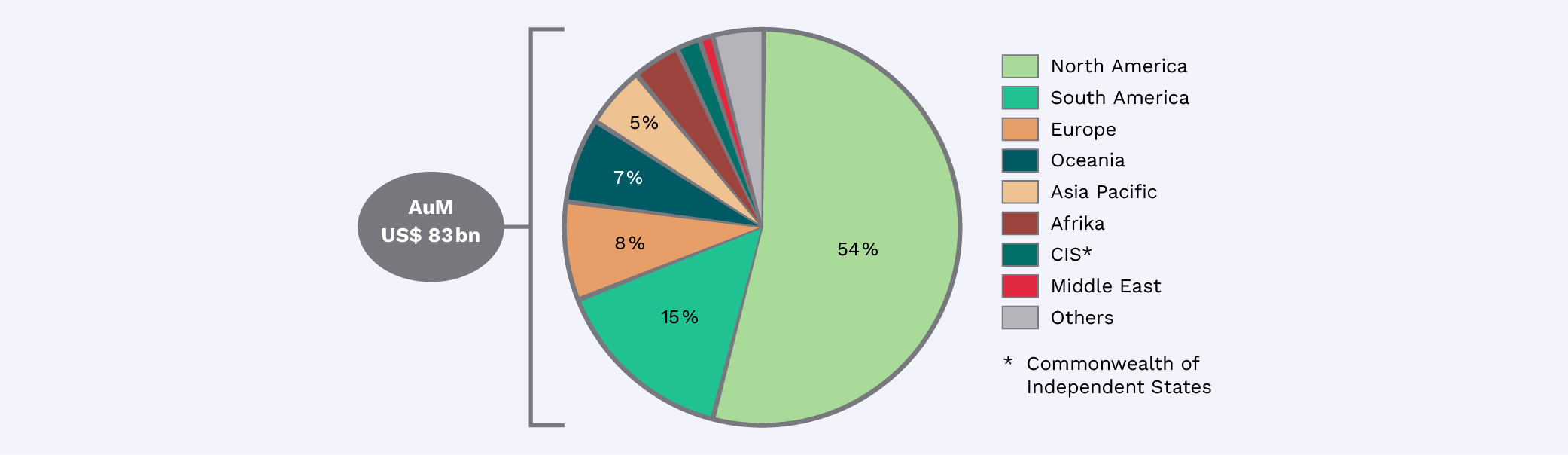

For the regional distribution of these investments, see the figure below. What is striking is that contrary to the “global land grab” discourse, the great majority of agri-investments has targetted countries in the Global North (with several of them though having a settler-colonial history).

Investment funds specialized in food and agriculture by main region. Source: Based on data provided by Valoral Advisors (2018). [1]

Investment funds specialized in food and agriculture by main region. Source: Based on data provided by Valoral Advisors (2018). [1] [1] Valoral Advisors (2018) Breakdown of investment funds included in Valoral Advisors’ database (by investment target, region and fund’s status: proprietary data bank). Luxembourg City: Valoral Advisors.

The story for country-based data on investment trends and patterns reads somewhat differently and is firmly entangled with what some scholars have termed “geopower”. It requires us to dive deeply into the question of how states not only regulate (foreign, institutional) investment flows into farming, but also how they account for them in public.

The kind of information on (foreign) investments in the farming sector that states provide depends on their capacity and willingness to make finance’s footprints and operations visible. As we shall see for the case of Aotearoa New Zealand (see here), in some cases, the state – for example, via public records about financialized farms – may allow us to gather information of use for political deliberation and decision-making. In other cases, the state may systematically obscure what is going on, or may simply be ignorant about such data (e.g., in the case of Tanzania).