Futures

of food production

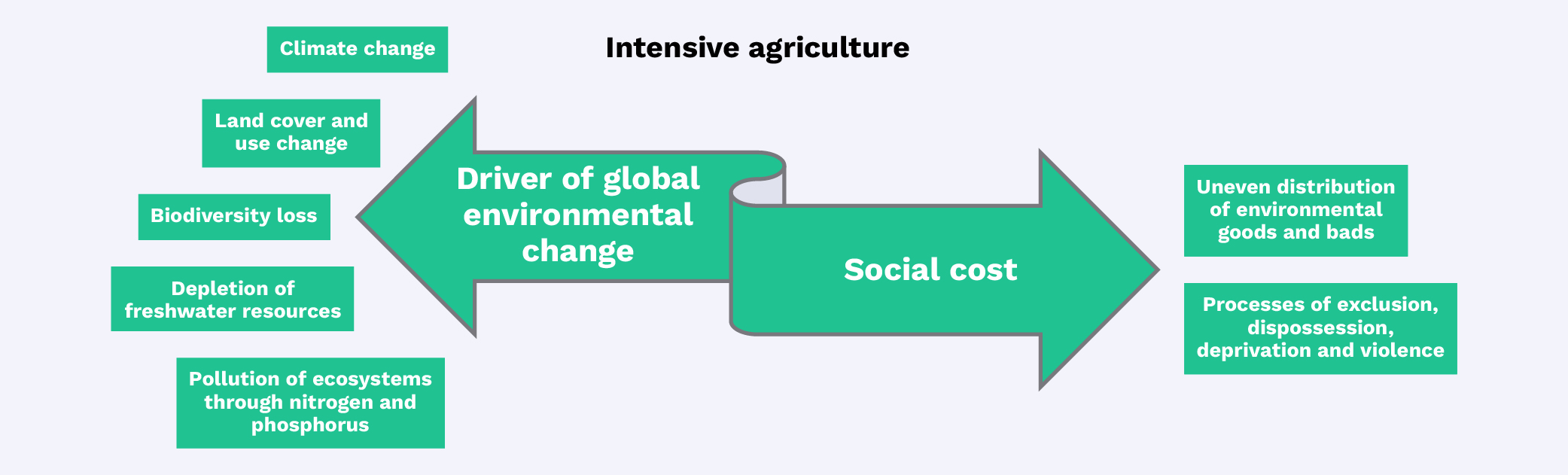

Consequences of intensive agriculture. Drawn from Ouma 2020: 167-179.

Consequences of intensive agriculture. Drawn from Ouma 2020: 167-179.

Intensive agriculture is one major driver of global environmental change. Agricultural operations around the world are also often linked to processes of exclusion, dispossession, deprivation, and violence, resulting in the uneven distribution of both environmental and economic bads among labour, capital, and rural communities.

(Ouma 2020: 167-179)

Feeding the world: model I

Due to the globalization of Western diets which implies more consumption of meat, dairy, and grain, these negative impacts could grow massively over the next decades. What is the role of financial investments in this story? Financial investors often present themselves as contributing to feeding the world, adding that the increasing emphasis on ESG will lead to more responsible and sustainable investments. However, recent studies show that most of the agricultural investment funds focus on row crops, animal protein, and dairy, all of which have high environmental (and social) footprints. Given the larger track record of industrial agriculture, the style favoured by most financial investments, many critical observers have argued that food production must be definancialized in order to curtail potential negative societal and environmental effects. However, some scholars have maintained that we should explore the possibility in terms of how the massive amount of financial wealth commanded by, in particular, institutional investors might be harnessed for more sustainable and less extractive futures. Could these often-public institutions be transformed from trustees of other people’s money to guardians of the planet?

When it comes to food production, three of the four cases studied in Aotearoa New Zealand, seem to align well with the older assertion that institutional investors could be model landlords – an idea first voiced before the first institutional farmland frenzy came to an end in the United Kingdom in the early 1980s. This idea could be expanded to incorporate “caring” investments into other stages of the agri-food chain, such as the capital placement by an impact investor in Tanzanian dairy processing.

Although I acknowledge that many asset managers and their operators on the ground often strive to better the world (and make some money at the same time), even the better cases of agricultural investment (and responsible and impact investment more generally) must be scrutinized for the deeper logics and principles of the landscape-making they embody (see also section on Global return society). A more intergenerational approach to institutional investment would be a viable mid-term strategy (which already would need a great deal of financial market restructuring and a willingness on the part of future pensioners and other types of financial beneficiaries to change their return expectations and lifestyles), but this does not necessarily transcend a range of problems that currently shape or are a product of “modern finance”. While coming from a different angle, even The Economist now acknowledges the limits of the dominant ESG model. In the Anthropocene, we must think in more substantial terms about our contemporary states of being and the potential futures that could emerge from them. This potentiality is often closed down in finance-driven renditions of the future in favour of a neo-Malthusian “techno- solutionism” via which the world is to be fed.

Feeding the world: model II

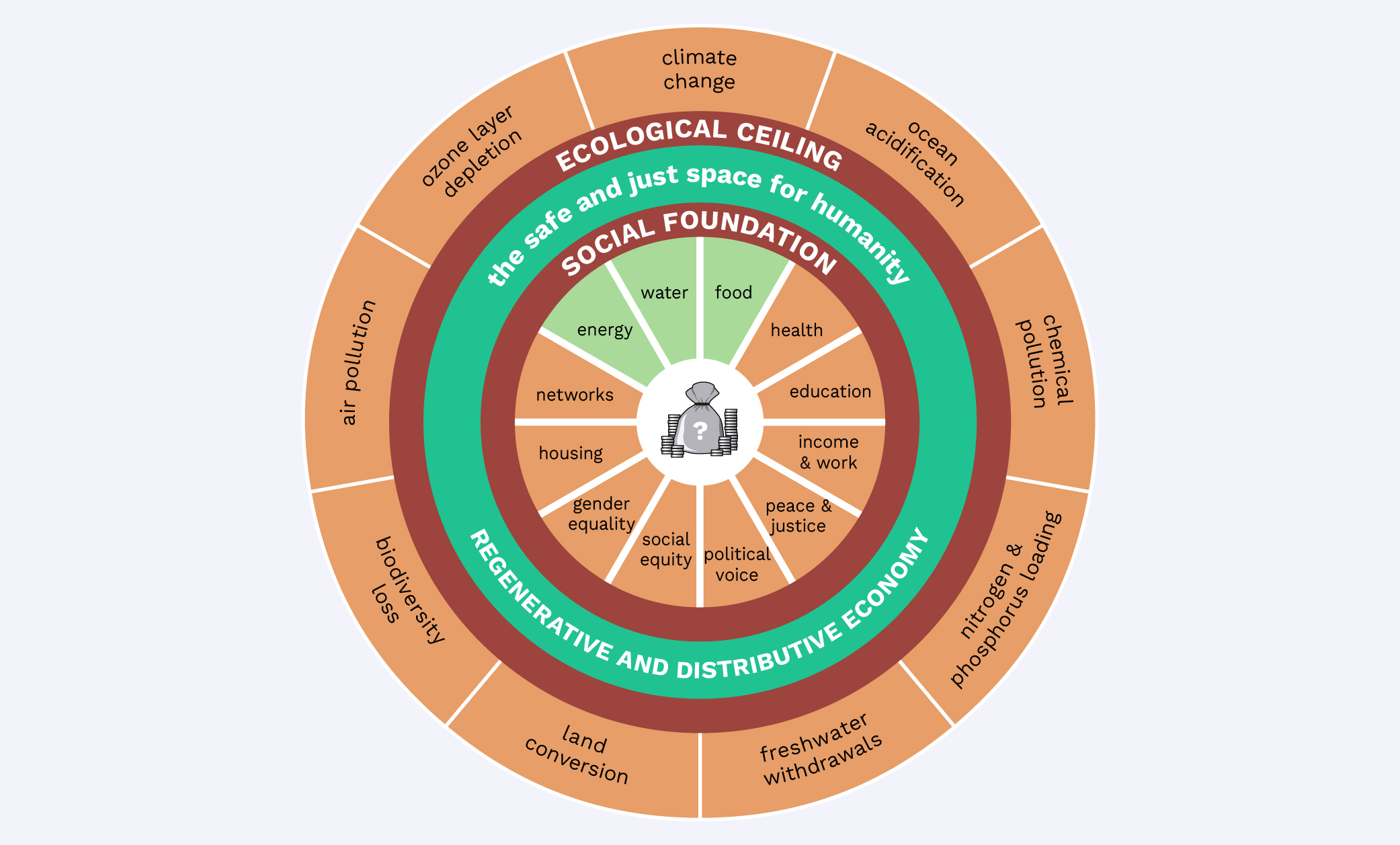

How to get into the doughnut, and the forms of finance that may help. Modified after Raworth 2017. Re-drawn from Ouma 2020: 178.

How to get into the doughnut, and the forms of finance that may help. Modified after Raworth 2017. Re-drawn from Ouma 2020: 178. Sustainable food and agricultural futures require more than technological or regulatory fixes or finance-as-usual with an enhanced ESG mandate. It requires radically different imaginations of how we live and retire well. Obviously, this is larger than food! Ideas abound and complement or enrich the post-capitalist politics envisaged by the authors just cited above. They obviously go beyond this research, but this should not make us shy away from a bit of radical imagination. “Radical” as an ethos needs to be reclaimed from its common association with being unjustifiably “extreme” or simply “utopian”. Rather, it should be understood as a call to go to the roots – “radical” derives from the Latin word radix (“root”; plural radices) – of the problem of modern finance. This implies acknowledging that a model built on imperial claims on the future and in need of constant expansion does not serve us well to get into the core of the “doughnut” [1].

Economist Kate Raworth came up with the concept of the doughnut model of the economy. The doughnut is a compass that allows us to develop a system that serves all well by meeting a range of basic social needs globally while making sure that we do not transcend the ecological limits or “planetary boundaries” of the Earth system [2]. Although Raworth could be challenged on the grounds that she promotes a “new idealism”, rooting all our economic-ecological malaise in flawed economic theory (and, indeed, more radical roadmaps to a world beyond capitalism exist), the doughnut probably still provides the most powerful visual model of how systemic, target-oriented and transformational knowledge can be brought together to carve out other kinds of food futures.

The realization of “doughnut agriculture” hinges on a whole variety of other interventions by governments, companies, grassroots movements, and individuals aiming at reshaping how we live, consume, produce, organize technology, distribute, care and retire. This ranges from stranding assets such as fossil fuels to rethinking the ways money is generated, circulated, and taxed, and to new forms of property (both material and intellectual) and corporate equity that are in line with a doughnut economy in which the relational ethics mentioned above can flourish. This would also imply drastically reducing the volumes of interest-bearing capital roaming the globe (various forms of debt, including pension- to- be- money), and, indeed, moving beyond an economic system based on the amassment of spatially extensive return claims. For agriculture, this could mean reinvigorating some of the ethics that cropped up in some of the Aotearoa New Zealand case studies. I am saying this in the full knowledge that these often served in a more instrumentalist way as a value proposition for investors. Such an agriculture would, rather, thrive on short investment chains – “community investments and relationship-based lending” [3]. The notions drawn from Māori philosophy such as kaitiaki (guardianship) and whanaungatanga (kinship), if adopted in a robust way, offer some interesting entry points in overcoming an “economy as machine” ethos. They could inform a more meaningful financial ethics that aims at ensuring there is “balance, collective custodianship or guardianship and respect for the spirit or the force of the natural world” [4]. Reducing the physical and relational distance not just between investors and investees but also between food consumers and producers within an agri-cultural system that harnesses accessibility, diversity, multifunctionality and intergenerational care could be an outcome of this.

[1] Raworth K (2017) Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. [2] Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, et al. (2009) A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461 (7263): 472-475. [3] Stephens P, Knezevic I and Best L (2019) Community financing for sustainable food systems. Canadian Food Studies/ La Revue canadienne des études sur l'alimentation 6 (3): 60-87. [4] Harris M (2017) The New Zealand project. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books: 200.