Value(s)

Making and unmaking an “asset class”

Land grab protests at the Euro Finance Week in Frankfurt 2013. Source: Ouma 2013.

Land grab protests at the Euro Finance Week in Frankfurt 2013. Source: Ouma 2013.

Central to the assetization of farming is the globally distributed effort to bestow it with a legitimate financial worth. Although many financial actors paint the picture that farmland has an absolute or intrinsic value and that this value can be “unlocked”, my research demonstrates that farmland gains its financial worth only through collective yet contested practices of classification, valuation, and valorization. This process has an internal dimension (related to the financial industry) and an external dimension (related to “society”). Within the finance industry, this involves its positioning of farmland as an “asset” in the relational investment universe of the world of money management: agriculture becomes a legitimate asset class only if it can be meaningfully set in relation to other asset classes, and if the underlying “assets” generate legitimate returns for investors. Assetization involves the production of a specific form of financial knowledge about the world of farming through which its social, material, and temporal qualities are aligned with the moral conventions governing the money management industry.

Furthermore, the legitimization of “agriculture as an asset class” has been thwarted by external forces such as NGOs. Their well-publicized accusations of the immorality (i.e., speculation, land grabbing) of finance-gone-farming have become major reputational risks for institutional investors. Take for instance this investment conference taking place in Frankfurt in 2013, where actual and would-be investors in farmland were welcomed by activists forming a “corridor of shame”, or the reports of German teachers finding out that their pension provider had invested in a “land grab deal” in Brazil.

This notwithstanding, “capital” and its enablers have worked hard to overcome these internal and external barriers to accumulation. Ultimately, the research presented here allows us to problematize the often-invisible morality of finance, which is as much about “value” as it is about “values”.

(Ouma 2020: 93-95)

External legitimization struggles

NGO campaign for pension funds' divestment from farmland and agriculture. Source: Ouma 2020: 105 (original source: Grain 2017).

NGO campaign for pension funds' divestment from farmland and agriculture. Source: Ouma 2020: 105 (original source: Grain 2017). In 2016 the NGO Friends of the Earth started a divestment campaign targeting TIAA, a US pension giant. It was not the first time that forces from outside the financial industry challenged the rising interest in farming among financial investors. It is particularly farmland-based investments that have come to pose a reputational risk for investors and their asset managers. One – asset manager interviewed even confirmed that the ‘land grab discourse’ can be considered to be one of the biggest entry barriers for institutional investors such as pension funds – the supertankers of the global asset management industry who make or break asset classes.

Opposition to farmland investments is a multiscale phenomenon: Global NGOs such as the Oakland Institute or Grain have launched many campaigns around the globe (see the example with TIAA), while at the same time capital placements in farming might be contested by various local and national forces, reflecting particular agrarian histories and a specific politics of place.

(Ouma 2020: 104f.)

Internal legitimization struggles

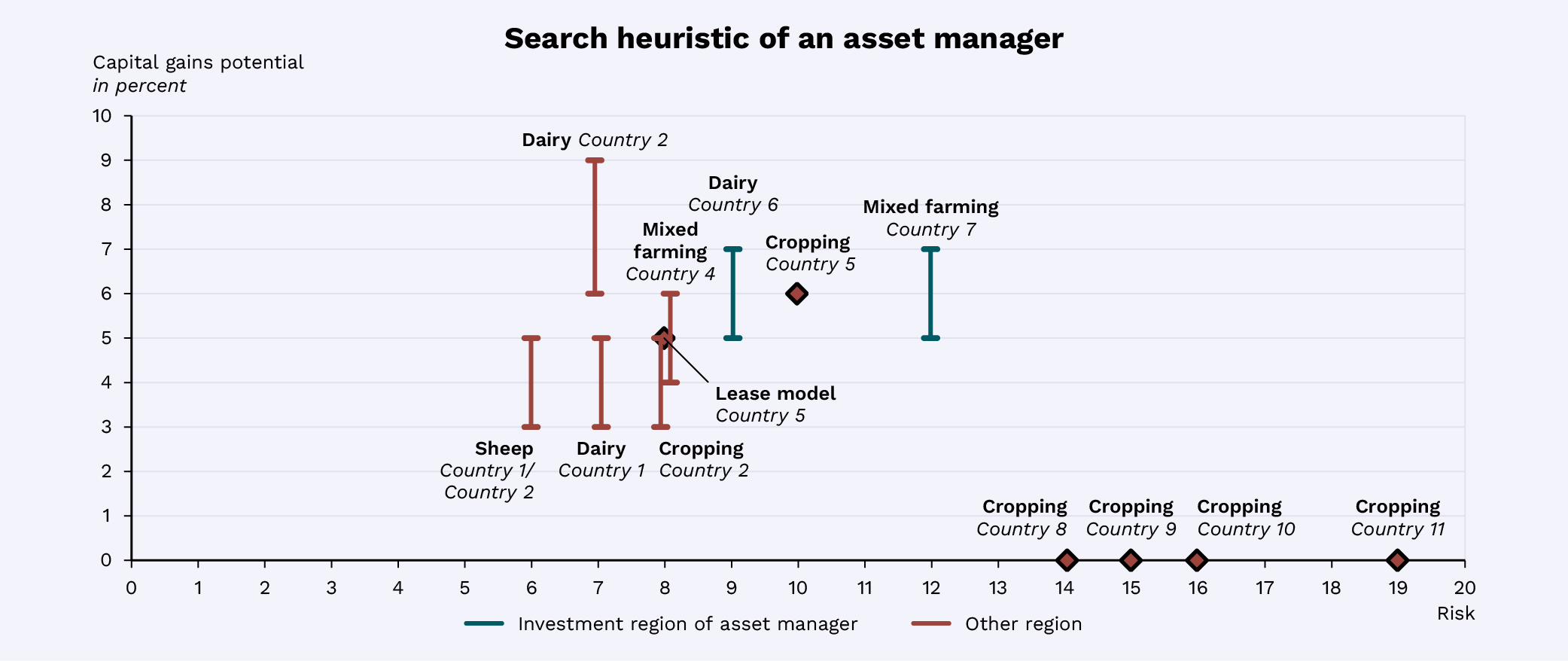

Rationalizing the investment process: An anonymized search heuristic of an asset manager. Source: Redrawn from data gathered.

Rationalizing the investment process: An anonymized search heuristic of an asset manager. Source: Redrawn from data gathered. The internal conventions of the money management industry have represented barriers to capital placements into farming, too. For many years, despite the hype, large investors have struggled to classify agriculture as an asset class in a meaningful way. Is it a real estate play? Or a private equity one? Or about commodities? Or about everything at once? In a world where many investment decisions need to be judged against hard data, the lack of granular agricultural data on a global scale has also hampered the flow of capital into agriculture. Furthermore, many land markets worldwide show only a weak institutionalization, resulting in both market and asset opacity. Even in more institutionalized contexts such as the US, land markets remain often opaque: some of the best properties never hit the market. Asset opacity across geographies has also made it difficult to measure the liquidity of farmland markets, something investors with large, diversified portfolios need to be concerned about. One asset manager interviewed tried to alleviate this by rationalizing the investment process via a search heuristic.

Another barrier to the assetization of farming has been the disconnect between the temporal logic of farming and the rhythms of institutional portfolio management. Farming is working on an annual logic whereas fund managers usually require quarterly reporting (or something even more frequent).

Furthermore, each investment deal always includes high transaction costs due to the need for information gathering, due diligence, legal services, and the like. This explains why large institutions have minimum investment thresholds. Compared to deals in other asset classes such as infrastructure or urban real estate, farming assets are relatively small and are thus often located beneath that threshold. For much of the period since 2007/08, investors interested in the space often could not draw on the experiences of invested peers since many of them had not yet exited their investments (or at least had been very secretive about their exit experiences).

Finally, investing in farmland is a rather complex business. Those in search of quick returns are misplaced: seasonality, the need to work with farmers who have “skin in the game”, the complex microgeography of farms, unpredictable market dynamics, political resistance, and labor issues among others often thwart a quick and easy assetization of agriculture.

To summarise, agriculture has still not emerged as a structurally coherent alternative asset classes due to both external and internal struggles about its nature.

(Ouma 2020: 100-103)

Responses from industry players

AG Investment Conference, Singapore. Source: Ouma 2013.

AG Investment Conference, Singapore. Source: Ouma 2013. How has the money management industry tackled these barriers?

When it comes to internal legitimization struggles, financial players have been taking steps to enhance the coherence and legitimacy of the “agriculture asset class”. This includes the proliferation of educational spaces such as institutionalized conferences on agri-investing (which serve at the same time as networking opportunities). Furthermore, new tools are being provided by specialized industry intelligence, e.g., the Savills Global Farmland Index that enables to compare historical farmland values for different regions. Also, firms have evolved that offer more granular data on agricultural assets, such as the US firm Acre Value, now a leading farmland real estate platform, or the asset manager spin-off Map of Agriculture.

In order to protect the farmland asset class from reputational risk, many industry players have reviewed their internal ESG criteria (more information on ESG here). However, an interviewed company representative pointed out the frictions remaining, because NGOs and asset managers would eventually talk in different languages. The public pressure on the agri-focused asset management industry also led to the launch of the “Principles for Responsible Investment in Farmland” in 2011 by several large institutional investors. A set of comparable principles had already been launched by the World Bank and others in 2010. The FAO also got involved in the “principles business” in 2014. Additionally, roundtables for specific assets such as soy, biofuel, and palm oil had been introduced. Several NGOs have criticized that these frameworks remain voluntary and are watered-down, but they represent a legitimization tool inside the financial world. Scholars have joined these voices, as for instance the recent books of political economists Jennifer Clapp and Ryan Isakson (2018) [1] and sociologist Madeleine Fairbairn (2020) [2] show.

Still, farmland investments constitute an aggregated risk to potential investors, events as the controversy around TIAA and its investment chain enhance this effect. To manage eventual reputational risks, some asset managers benefit from specialist intermediaries. This makes clear that potential land grabs or adverse ecological impacts do not count as moral questions, but matter as a threat to value creation. Moral and social questions thus become economic ones.

(Ouma 2020: 106-109)

[1] Clapp J and Isakson SR (2018) Speculative Harvests: Financialization, Food and Agriculture. [S.I.]: FERNWOOD PUBLISHING. [2] Fairbairn M (2020) Fields of gold: Financing the global land rush. Ithaca [New York]: Cornell University Press (Cornell series on land: perspectives in territory, development, and environment).

Placing finance in the global land rush

The above-mentioned protestors at the Euro Finance Week are only part of a wider movement that has contested the acquisition of farmland and agricultural ventures by financial actors around the globe, particularly in regions of the Global South. Webpages such as farmlandgrab or the Land Matrix are indicative of this.

(Ouma 2020: 93)

Financial investors have been one of the main drivers of the so-called “global land rush”, in which non-financial entities, such as state-run or parastatal companies or other types of corporate entities, also have played a crucial role. Investors searched for new alternative assets, especially since the financial and food price crises of 2007/8. Farming seemed to be a safe financial bet since the world population is growing, the demand for meat and protein in emerging markets is rising, the use of agrofuels is increasing and farmland as a resource is limited.

Nevertheless, the rising interest of global finance into the so-called AG space needs to be compared to investments in other asset classes. In 2018, investment funds specializing in food and agriculture had assets under management worth about US$83 billion in total – tiny compared to the US$533 billion in natural resources globally (2017).

(Ouma 2020: 1f.)

Furthermore, we need to take a closer look at the true scale of this finance-driven part of the global land rush. In the early land rush literature, it appeared as if investors were mainly pursuing large-scale land acquisitions in Africa, South America and the central and eastern European and Commonwealth of Independent States regions. This picture (especially of Africa being the prime frontier region of the global land rush) was a misinterpretation of the actual dynamics. A more differentiated and complex picture has been emerging. The core regions where large-scale agricultural capital placements driven by financial investors have focused on are North America, South America (particularly Brazil), Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand. Financial placements into African farmland make up only a small share of the total number of funds targeting African food and agricultural sectors (in Oceania and North America, this share is 10 to 18 times bigger).

(Ouma 2020: 58-61)