History

Colonial and post-colonial agrarian landscapes

History retold@Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Photograph taken by Stefan Ouma 2014.

History retold@Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Photograph taken by Stefan Ouma 2014. The production of settler-colonial agrarian landscapes in contemporary land rush frontiers such as Aotearoa New Zealand cannot be discussed without considering the far-flung financial networks that linked “the city” (metropoles such as London) and “the countryside”. If space permitted it, similar accounts could be provided for places such as the United States, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Uruguay, or South Africa, where “within three generations, during the nineteenth century, some of the best lands [were] secured, surveyed, apportioned, registered and drawn into finance capitalism” [1]. In these places, finance had its own ways of extracting surplus from farming. Although stock-listed or shareholder-based private enterprises were crucial drivers of colonization, generating both dividends and rent for shareholders (e.g., by leasing it out to settlers), the provision of credit was an equally crucial element in the “terraforming” of the planet. As the case of New Zealand as both colony and independent nation-state shows. Although credit was often provided by national governments, even these would often borrow from international markets or financial institutions to provide agricultural credit to Pākehā farmers (the Māori name for white settlers) settling on land often dispossessed from various Māori tribes. Smaller settler farms would often compete with large estates, whose powerfully and resourced owners commanded much of the colony’s land: in the 1890s just “422 individuals and companies (less than 1 per cent of all landowners) controlled eight million of the total twelve and a half million acres of freehold land in 1890” [2].

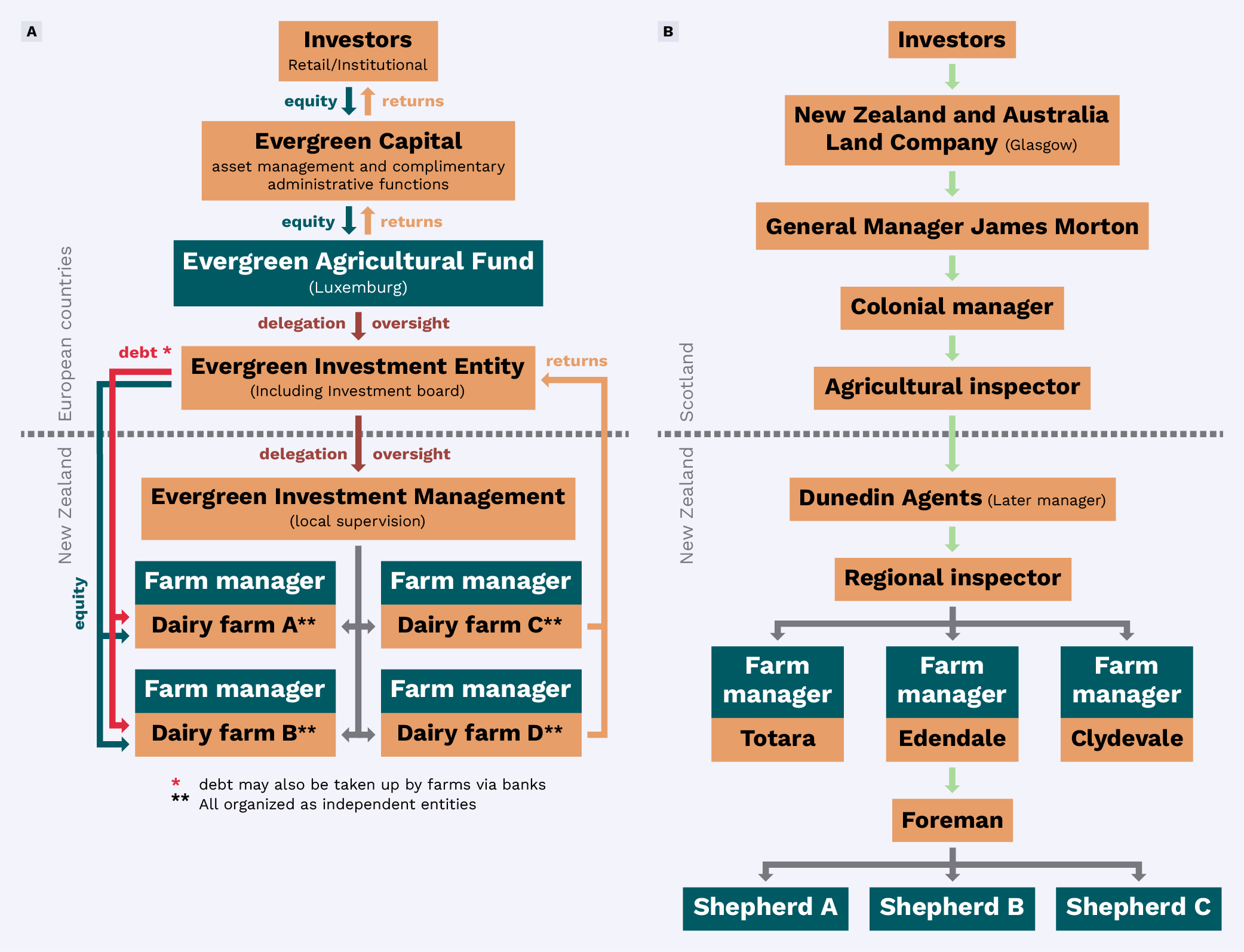

One of these companies was the New Zealand and Australian Land Company, founded by Scottish financier James Morton in 1865/ 6. The company acquired dozens of properties in the Southland and Otago Regions, turned them into “British farms” by introducing European flora and fauna, and established the first frozen meat exports to the colonial motherland in 1882. In later years it also leased out and sold land to settlers. The company “established a managerial structure which linked specific places on both sides of the world and allowed directly for the transfer of financial capital, technology, skills and raw materials” [3]. This structure, when juxtaposed against contemporary financial investments in Aotearoa New Zealand agriculture, looks all too familiar (see the figure below). In the case of the Land Company, as well as other estates backed by metropolitan finance, a shareholder value gaze “penetrated the production sphere of pastoralism” [4] at a surprisingly early juncture, “institutionalising the managerial goals of closely supervising production, enhancing productivity and rationalising the enterprise with various technical developments involving fixed capital investment” [4].

The owner-occupation of farms first established during colonial times, and later flourishing in the country and many other state-backed credit agricultural economies across the globe, veiled the fact that such credit relations – at the very core – would often qualify as rent relations as much as contemporary institutional investments in farming, even though the mode of rent production from agriculture has profoundly changed. Paradoxically, the ongoing expansion of credit in a country such as Aotearoa New Zealand over the past 130 years or so not only transformed agricultural landscapes but also created an opportunity for new forms of capital to enter farming, as a result of increasing debt levels among local farmers. In contrast, in Tanzania, the other case study context for this research, it has been precisely the absence of credit for smallholder farmers – a condition with firm roots in the colonial era – that has justified the search for new forms of financing agricultural transformation.

(Ouma 2020: 29-33, 42-44) [1] Weaver JC (2003) The great land rush and the making of the modern world, 1650-1900. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press: 89. [2] Wynyard M (2016) The price of milk: primitive accumulation and the New Zealand dairy industry 1814-2014. University of Auckland: 89. [3] Tennent K (2013) Management and the Free-Standing Company: The New Zealand and Australia Land Company c 1866-1900. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 41 (1): 81-97: 91. [4] McMichael P (1987) The Relations between Capital and Landed Property: A Reply to Fairweather. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology 23 (3): 423-432: 431.

Comparison between the architecture of a contemporary dairy fund (A) and the New Zealand and Australian Land Company (B, New Zealand branch only). Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 31.

Comparison between the architecture of a contemporary dairy fund (A) and the New Zealand and Australian Land Company (B, New Zealand branch only). Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 31.