Present-time

State-regulation of FDI in agriculture

Despite the widespread narrative that, in the age of financialized capitalism, the state has been rolled back, with its remnants somewhat helplessly watching how restless capital hops from place to place, it still plays an important role in the regulation of foreign direct and portfolio investments into agriculture and other domains. The regulatory capacity of the state is, of course, highly uneven, but, more importantly, it appears in varied and sometimes surprising ways. In many countries, the state has been central in giving rise to the asset management industry that we know, and the capital flows the latter administers cannot be thought of without the productive powers of the former. To name but a few examples: state regulation deeply shapes the fiduciary and delegation practices underpinning global investment chains; the state often acts as a grantor of land and the property rights that are so central to the making of institutional landscapes inside and outside agriculture; state regulation also shapes how much value can be extracted from agricultural labour and nature, and how much of this is being redistributed domestically as part of taxation arrangements.

From Britain's farm to the world's farm

Aotearoa New Zealand kept close links to its former coloniser. Until the 1970s, its agricultural exports depended on the United Kingdom. The British entry into the EEC (European Economic Community) in 1973 disrupted this metropole-satellite relationship (with the Island basically serving as “Britain’s farm”). The country slid into a deep economic crisis, which led to a radical neoliberal overhaul from the 1980s onwards. In the wake of neoliberal agricultural restructuring, the traditional, state-credit-backed model of family farms would soon be a thing of the past. Business-savvy farmers rolled out new organizational structures such as syndication and equity partnerships as part of a more corporate-oriented farming model. Multiple farm ownership, “corporate style” and often highly leveraged with private credit, became more common. The largely state-owned forestry sector was equally disrupted and privatized. The most recent wave of agricultural investment, starting in the late 2000s, is grafted onto the landscape that 30 decades of neoliberal restructuring had left behind.

In the early post-global financial crisis days, the country was considered an investment Eldorado for its welcoming regulatory environment, its stimulating agricultural policies, its rising land prices, the relatively good management of the crisis, its proximity to Asian markets as well as the lack of capital gains tax on the sale of assets. This resulted in the increasing influx of institutional investors, as well as agrobusiness internationals, amounting to rising investments in primary production (such as beef, dairy, and viticulture) as well as processing.

(Ouma 2020: 71-73)

If you want to learn more about the trajectories of Aotearoa New Zealand agriculture from a historical perspective, and the emergence of “modern” agricultural productivism, watch this video by one of the foremost experts in this field: Professor Hugh Campbell (University of Otago).

Regulating agri-investment flows in Aotearoa New Zealand

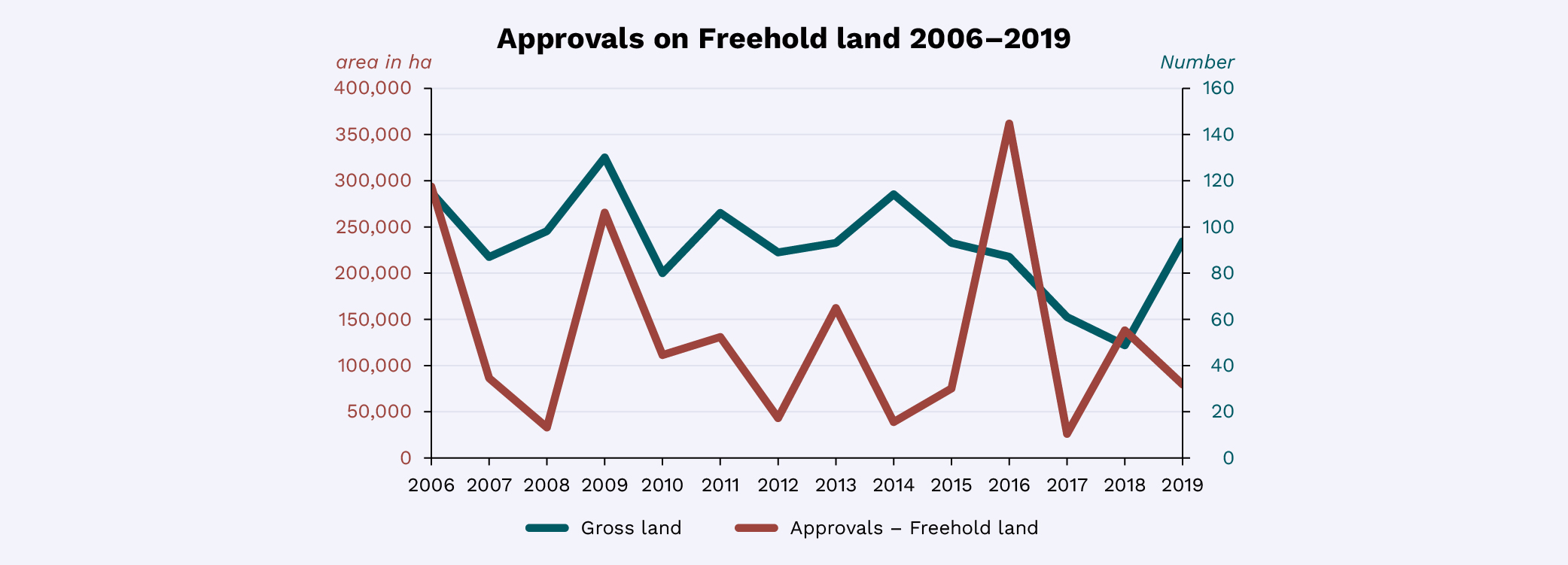

OIO approvals (gross) of freehold land purchased by foreign investors in the agriculture and forestry sectors of Aotearoa New Zealand, 2006-2019. Chart created after Land Information New Zealand 2021. Source: https://www.linz.govt.nz/overseas-investment/decisions-summaries (accessed 2 November 2021).

OIO approvals (gross) of freehold land purchased by foreign investors in the agriculture and forestry sectors of Aotearoa New Zealand, 2006-2019. Chart created after Land Information New Zealand 2021. Source: https://www.linz.govt.nz/overseas-investment/decisions-summaries (accessed 2 November 2021). The entry point for financial investors interested in farming in Aotearoa New Zealand is the Overseas Investment Office (OIO) which approves all foreign investors and publishes information online on a regular basis (see figure above). Thanks to the information granted by the OIO, we can develop a quite good understanding of the foreign investment patterns in the “AG space” in Aotearoa New Zealand. We can speak of a thick institutional landscape since the OIO data provides lots of information, which puts us in a position to arrive at a thicker-than-usual description of how global finance has flown into the “Kiwi countryside” over the past years. Globally, this investment data remains unmatched. Although certain information may not be made public at the request of the investors, and approval does not necessarily mean that these deals eventually materialize, these accounts can still be used to develop a fairly good understanding of the scale, geographies, and temporal patterns of foreign investment into farmland, agriculture, and forestry. If you want to learn more about data problems with regard to the phenomenon of finance-gone-farming at a global level, click here.

The concrete operations of the OIO need to be embedded into the larger political economy of the post- 1984 era, whereby the dominant governing parties Labour and National may have differed here and there, but both have “courted foreign investment” (interview, journalist, 2018) to such an extent that many investors would think “both parties run the same” (interview, industry expert, 2018). Free-market thought has also deeply infiltrated society, thus constructing a novel “common sense” surrounding “reasonable” economic policy, both generally and with particular reference to farming. The so-called “New Zealand experiment” (coined by New Zealand scholar Jane Kelsey in her 1995 book) not only led to the demise of family farming, and to increased land consolidation and concentration, but also gave rise to a new class of business-oriented farmers backed by private credit and equity, a new culture of productivism and a more diversified and highly competitive agricultural sector, which had dairy, viticulture, and horticulture added to – and sometimes even surpassing – its traditional exports: sheep and beef. With farms getting bigger and bigger, especially in dairy, the “capital climate was getting bigger”, too, as one observer put it (interview, journalist, 2018). This also involved new business models, such as equity partnerships, whereby investors (farmers and non-farmer) acquire land and hire a farm manager who co-invests with them. This model breathes the spirit of private equity and has been practised by domestic and foreign investors alike. At least for many domestic dairy corporate investors and family farmers, this has also often involved the practice of “leveraging themselves into growth”, as one observer put it (interview, representative asset manager, 2018).

(Ouma 2020: 73f., 78)