Present-time

State-regulation of FDI in agriculture

Despite the widespread narrative that, in the age of financialized capitalism, the state has been rolled back, with its remnants somewhat helplessly watching how restless capital hops from place to place, it still plays an important role in the regulation of foreign direct and portfolio investments into agriculture and other domains. The regulatory capacity of the state is, of course, highly uneven, but, more importantly, it appears in varied and sometimes surprising ways. In many countries, the state has been central in giving rise to the asset management industry that we know, and the capital flows the latter administers cannot be thought of without the productive powers of the former. To name but a few examples: state regulation deeply shapes the fiduciary and delegation practices underpinning global investment chains; the state often acts as a grantor of land and the property rights that are so central to the making of institutional landscapes inside and outside agriculture; state regulation also shapes how much value can be extracted from agricultural labour and nature, and how much of this is being redistributed domestically as part of taxation arrangements.

The 'last frontier'

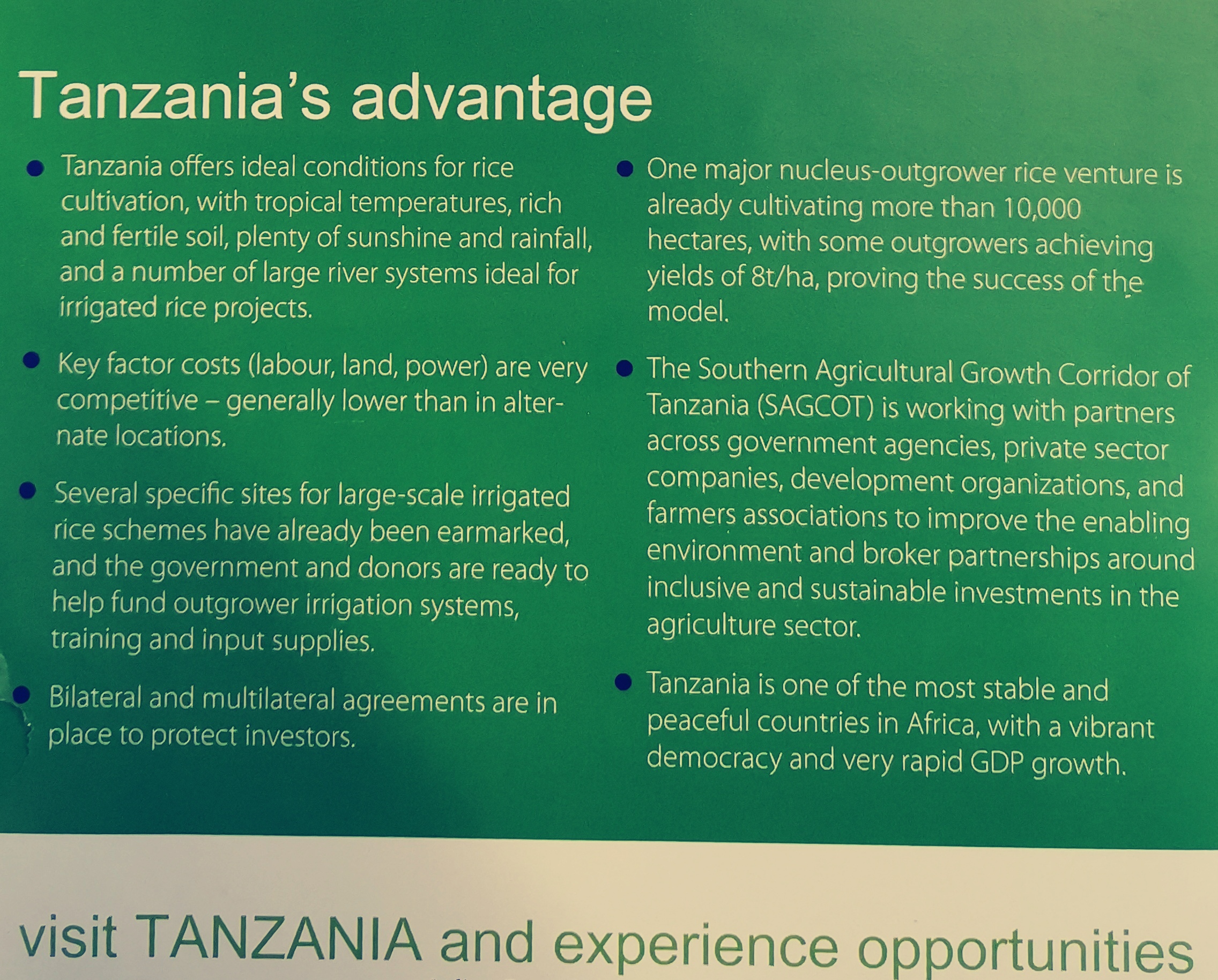

"Frontier advertisement" by SAGCOT and the TIC. Source: Ouma 2017

"Frontier advertisement" by SAGCOT and the TIC. Source: Ouma 2017 Africa has been heralded as the “last frontier” in global food and agricultural markets. Here, it is said that large reservoirs of “underutilized” land can be valorized for food/ agrofuel production and carbon sequestration; “yield gaps” can be closed; hidden value can be “unlocked”. Many African governments have responded to this new global interest in all things agricultural as part of a market-oriented agricultural policy agenda that has been on the rise since at least the mid-2000s. This agenda no longer fits smoothly with the so-called Washington Consensus, with its free-market credo, for it wants to actively intervene in the economy in order to build national, regional, and global market connections. The rise of value-chain agriculture and the renaissance of contract farming have to be seen in this context. More recently, however, this debate has been tilted in interesting ways. Although most major development organizations – including the World Bank – have usually based their market-oriented agenda on faith in smallholders, it is now increasingly being questioned whether smallholders can feed the world [1]. Consequently, agribusiness and (large-scale) commercial farms have climbed to the top of African agricultural policy agendas since at least 2010. Tanzania relates in interesting ways to these developments. After its independence, the country embarked on a socialist development path (in Kiswahili known as Ujamaa) that resulted in the Arusha Declaration in 1967. The latter resulted in a dual agricultural strategy, which sought to transform agrarian structures through the villagization of rural households as well as through the development of large mechanized state farms.

With the withering away of socialism from the mid-1980s onwards, agriculture was at first largely neglected as a domain of structural transformation by successive governments. It was only in the late 1990s that the government started to give “agricultural modernisation” greater attention in its Vision 2025, which envisaged that “the economy will have been transformed from a low productivity agricultural economy to a semi-industrialised one led by modernised and highly productive agricultural activities” [2]. The Agricultural Sector Development Strategy (ASDS), launched in 2001, and the Agricultural Sector Development Programme (launched in 2006), the practical implementation of the former, encapsulate this transformative vision. Both emphasized a public-sector-based and smallholder-oriented development agenda that aimed at enhancing productivity through increased investments in irrigation and agricultural services.

(Ouma 2020: 74-75)

[1] Collier P and Dercon S (2014) African agriculture in 50 years: Smallholders in a rapidly changing world?. World Development 63: 92–101. [2] Ministry of Finance and Planning (1999) The Tanzania Development Vision 2025. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Finance and Planning: 2.

From Kilimo Kwanza to SAGCOT

Promotion of the "SAGCOT spirit" in a Tanzanian Newspaper. Source: Ouma 2017.

Promotion of the "SAGCOT spirit" in a Tanzanian Newspaper. Source: Ouma 2017. In the wake of the recent global financial and food crises, however, Tanzania’s agricultural policy landscape experienced a notable transformation when the then president, Jakaya Kikwete, launched the Kilimo Kwanza (KK: “Agriculture First”) vision at a splendid hotel in Dar es Salaam in 2009. Even though the Tanzanian government subsequently launched a set of other policy frameworks, and developed a new agricultural policy in 2013, it was actually KK that made headlines as the de facto agricultural vision for Tanzania until there was a change in government in 2015.

Authored by the Tanzania Business Council (TBC), a body made up of both public and private sector organizations (rather than the usual government or donor agencies) and chaired by the Tanzanian president, KK was significant in that it pushed the more public sector-driven, productivist and smallholder-oriented agenda of the existing policy mix “towards the market” [1]. Its focus on large-scale farming, capital-friendly land legislation, agricultural finance, and potential joint ventures with foreign capital “reflected the emergence of a national commercial farming lobby” [2]. KK was soon followed by the launch of the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) strategy at the regional World Economic Forum held in May 2010 in Dar es Salaam. Advancing a now familiar trope in the land rush context, the growth corridor concept seeks to incorporate areas with “yield gaps” or “idle”/ “unused” land into modern market relations. The material realities of land tenure and ownership have often been sidelined in such discourses. For instance, in the context of SAGCOT, government and state officials have repeatedly claimed that Tanzania had 44 million hectares of arable land, but that only 24 per cent was being used. Much of this “idle” land is said to be in the SAGCOT corridor.

For many critical observers, the rise of KK and SAGCOT represents just the latest phase in Tanzania’s shift from peasant-oriented African socialism to capital-oriented neoliberalism. Issa Shivji [3], a Tanzanian law professor argues that years of market-oriented restructuring had turned the old mantra of the Arusha Declaration upside down, in that money (including foreign capital) was the outcome of development, not its basis.

Nevertheless, although such an interpretation raises important questions about the political economy of transition in Tanzania, it tends to forget that the governmental rationality engrained in SAGCOT, the underlying problematization of subsistence agriculture and the call to modernize agriculture have a long history, which stretches back through the early postcolonial period to the colonial state’s agricultural policies. The socialist Tanzanian state operated with a modernizationist ethos similar to that of SAGCOT [4], envisaging a space of social and economic transformation based on simplifying assumptions about both the population and agricultural systems “therein”.

The family resemblance between SAGCOT and a socialist modernizationist ethos becomes clearer if we take the example of a grain project discussed here as Case Study 2. At the time the company that had taken over this former socialist friendship farm was still operational, one was greeted by the painting below of the farm produced a long time ago. Although it is doubtful if the farm ever looked like that in the past, the painting nevertheless encapsulates the modernizationist rationale associated with parts of the Tanzanian socialist project. In an interesting twist of history, it was only after the collapse and sale of the state farm that the reality started to match the vision – after North American private equity and European development finance have taken over the farm. What appears as an irony of history is, rather, a confirmation of James Scott’s thesis that high modernism may be engrained in both state- socialist and capitalist agriculture, with the latter having been heavily influenced by the former [5]. The state farm structures that Tanzanian socialism left behind seem attractive for financial investors, for whom scale is an important feature in shaping their investment decisions. Although scalability is often an objective in its own right – for example, when it comes to assessing the market potential of certain business models – it is often also desired because large institutional investors have minimum investment thresholds in order to keep transaction costs low. For large beneficiary institutions, it is often easier to invest US$20 million than US$2 million.

(Ouma 2020: 75-77)

[1] Maghimbi S, Lokina R and Senga M (2011) The agrarian question in Tanzania?, State of the Art Paper 1. Dar es Salaam: University of Dar es Salaam: 46. [2] Cooksey B (2013) The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) and Agricultural Policies in Tanzania: Going with or against the Grain? Brighton: Future Agricultures: 25. [3] Shivji I (2006) Let the People Speak: Tanzania down the Road to Neo-Liberalism. Dakar: Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa. [4] Schneider L (2007) High on modernity? Explaining the failings of Tanzanian villagisation. African Studies 66 (1): 9–38. [5] Scott J (1998) Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press: 200.

The rise of Magufuli and the end of SAGCOT?

Report in a major Tanzanian Newspaper on the SAGCOT pull out of JP Magufuli's Government in 2019. Source: Citizen 2019. URL: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/tanzania-government-cancels-sh100bn-sagcot-scheme-2681476 (last accessed 26 August 2022).

Report in a major Tanzanian Newspaper on the SAGCOT pull out of JP Magufuli's Government in 2019. Source: Citizen 2019. URL: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/tanzania-government-cancels-sh100bn-sagcot-scheme-2681476 (last accessed 26 August 2022). Of course, these insights should not downplay the fact that several contextual factors and the orientations and aspirations of economic policy-making in Tanzania have radically changed over the past two decades and the country had become more liberal, deregulated and populated by city society forces and political forces challenging the state and its ruling party CCM. However, when John P. Magufuli was elected the new president of Tanzania in 2015, the country changed track and borrowed selectively from the Socialist era. His government has tried to advance a state-centered development model with an authoritarian face and has privileged the promotion of “factories” (i.e. industrialization) over that of agriculture.

Its highly interventionist and often-unpredictable actions turned off many potential investors and scared those who already had invested in Tanzania, the more so since land was repossessed from at least two large-scale agriculture investment cases. It also resulted in a significant downscaling of SAGCOT after the Tanzanian government cancelled a US$70 million loan facility of the World Bank linked to the project in 2019. SAGCOT was eventually further weakened by the Magufuli administration in 2020. What comes next under President Samia Suluhu Hassan, who followed Magufuli upon his death in March 2021? After all, Kilimo Kwanza and SAGCOT are still alive.

(Ouma 2020: 75-77)