October 19, 2023

#11: The Promise and Pitfalls of Using Land Titles Data to Track Agricultural Land Ownership – An Australian Perspective

Australia has been one of the hotspots of the finance-driven land rush – a fact that is sidelined in Global-South-centred accounts of the phenomenon. Economic geographer Bill Pritchard and law scholar Cathy Sherry offer methodological insights into how they made use of the Torrens system-based public land registry in Australia to map evolving patterns of corporate land ownership in the state of New South Wales from 2004 to 2019. Given that the land registry was leased to a private entity in 2017 which enclosed the data, their account also shows how research on (financialized) land ownership is entwined within the political economy of land titles data provision.

***

In a previous contribution to this website, André Magnan and Annette Aurélie Desmarais shared their experiences of using land titles data for their research into farmland acquisitions by large-scale investors in the Canadian Prairies. This contribution complements their work by discussing parallel issues in Australia. We address two issues. First, we reflect on the political economy of land titles data in the state of New South Wales (NSW), where both of us live and do most of our research. Second, we review land titles data as a method to track agricultural land ownership change in NSW, based on the experience of one of us (Pritchard) in a recent research project.Any discussion of these issues in Australia needs to acknowledge that present-day land titles are artefacts of Indigenous dispossession. Upon exercising sovereignty over the Australian landmass, the British colonisers granted interests over lands to which Indigenous people possessed native title, and in this process, extinguished those pre-existing title rights. As noted by Justice Brennan of the High Court of Australia in the historic Mabo judgement of 1992, “Aborigines were dispossessed of their land parcel by parcel, to make way for expanding colonial settlement. Their dispossession underwrote the development of the nation [1].”

Political economies of land registers in an Australian context

The capacity to grant interests over land was central to the project of colonial governance in Australia. Grants were made to incentivise agricultural and mining exploitation of land for the benefit of Britain. However, as invasion and colonisation are opportunistic and unpredictable, no clear plan had been devised for land grants. The ‘system’ was chaotic, both in relation to the initial executive powers used to make grants, as well as subsequent transfer of those grants between citizens. With a highly mobile population of strangers, by the mid-19th century there was widespread confusion and dispute over land ownership in the Australian colonies.A solution was devised in the Torrens system of land registration. Unlike land registration systems in many countries that simply record titles obtained through deeds (and sometimes give greater enforceability to registered deeds), the Torrens system re-grants a state guaranteed title each time registration occurs. Unregistered interests are unlikely to be enforceable – even when others are aware of their existence – and as a result, almost everyone registers. That in turn makes the Torrens register an extremely reliable picture of land ownership. As registers are publicly accessible for a fee, legal ownership of all land is transparent. Transparency matters not simply for individual purchasers but for the wider community. For example, it can be an important tool in efforts to curb money laundering and corruption [2].

In NSW, the Torrens register was created and managed by legislated agencies wholly within the machinery of government until 2017, when it was leased to Australian Registry Investments, a private sector consortium led by Hastings Funds Management and First State Super, for AU$2.6 billion (approximately US$2.0 billion at the prevailing exchange rate). This occurred despite universal objection from the legal and surveying professions, and the real estate industry. Ironically, given the transparent nature of the register itself, neither the scoping study nor lease of the register have been made public. Griggs and Low argue that this has made it impossible to assess whether appropriate safeguards in relation to the integrity and reliability of the register have been put in place or even whether commercialisation was economically beneficial [3].

What has happened in NSW is not unique in international contexts where reliable land registration systems exist. The justificatory discourse defending such shifts draws in arguments about private sector flexibility and efficiency in an era of big data. As stated in a World Bank blog from 2017: “The advancement of technology in the last two decades, including GPS technology, web-based services, mobile technology, and drone mapping, has made cadastral surveying and mapping much faster, cheaper, and more accurate…. The private sector, with its ability to raise money, flexible salary structures, budgeting finesse, and management skills, can offer solutions to some of these challenges [4].” However, what is remarkable about these arguments is: “the implication that a government organisation, apparently, can never be working cost-effectively and efficiently. Market ideology and politics seem to be driving the arguments, not actual empirical (i.e. data-driven!) analysis. [5]” A closer truth is the simple observation that the market price of a land registry “is so prodigiously high that governments cannot resist its attractiveness” to sell [6].

Further, the techno-fix advanced by these arguments deflects from important issues for public policy. The entry of private sector interests in these jurisdictions does not alter the status of land records as public documents but can reorient systems for data access. Two legal scholars point to the obvious: “The incentive for a private corporation to run a register will invariably be access to information to be packaged and sold for profit. Indeed, what other incentive would cause private enterprises to become involved?” [7]. A review of these issues from Canada concludes that this direction of change: can lead to: “the ‘public’ nature of land registry data [being]… challenged and compromised” [8]. These points are highly germane to the unfolding of a recent research into agricultural land ownership in NSW, as we now describe.

Using land titles data to track agricultural ownership change in New South Wales

In 2018, one of us (Pritchard) was awarded an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant to investigate rural land ownership change in NSW. The project was co-partnered with the NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI) which was interested in exploring how land titles data could assist the monitoring of change on agricultural lands. At the project’s commencement, DPI lodged a data extraction request on the researcher’s behalf with Land Property Information (LPI), the custodian agency at the time responsible for the land titles register. An accompanying Human Ethics Research Protocol approved by the University of Sydney covered the researcher’s obligations to maintain data security and ensure privacy. Through this mechanism, a bulk download of land title records from 2004-17 was provided to the researcher. Then, in 2020, land title records for 2018 and 2019 were also obtained through a similar request. These data requests took place after the registry’s operations had been transferred to the private consortium as described above but were consistent with pre-lease arrangements which allowed bulk data access for research projects with approved ethics protocols, on payment of a nominal administrative fee.Over the next few years, the project generated a series of research outputs that used the data to analyse rural trends in NSW [9]. As discussed in those outputs, this methodology does not come without challenges. As detailed in one of the Working Papers for the project, the minutiae of spelling errors and naming inconsistencies within the land titles database created major headaches for identifying trends [10]. As an example, if “John Smith” is a large farmer in a district and an adjoining farm is bought by a “Jonathon Smith”, should this be interpreted as a concentration of ownership or a separate owner? From the land titles data alone, it is impossible to tell. In the project, a fuzzy logic method was developed to interpret such events.

These types of problems are also manifested when seeking to track corporate ownership of farmland. Corporates can hold land titles in the names of different subsidiaries, and for a researcher, linking this to a common corporate parent can be done only with extensive (and time-consuming) cross-checking with business registers. The foreign ownership of agricultural land has been a hot button political issue in Australia, but using the land titles database to identify foreign owners is problematic because of their use of locally incorporated subsidiaries as vehicles for owning land. It is infeasible to cross-check thousands of corporate landowners with business registries to ascertain ultimate ownership of land assets.

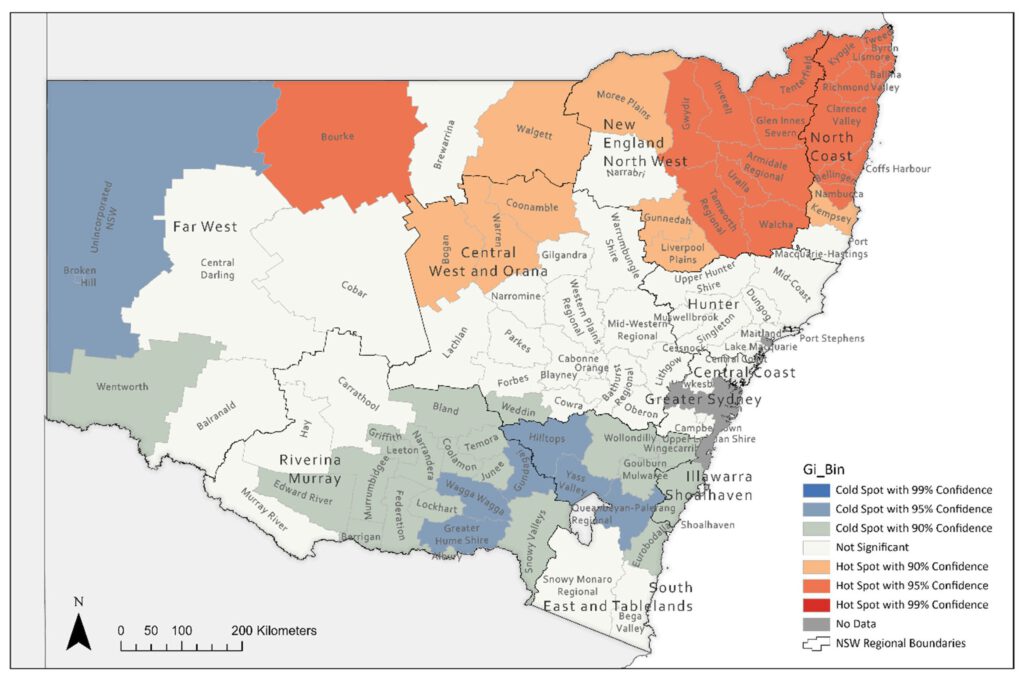

Notwithstanding these challenges, the project successfully identified key trends in NSW rural land ownership. It found that rural land markets have become increasingly volatile. Hot Spot analysis using the Getis Ord GI* statistic identified locations with high rates of rural land ownership change. As shown in Figure 1, northern NSW was a hive of intense land ownership change, while the southern add far western areas were the opposite. Reasons for this are expanded upon in a project Working Paper [11], but this analysis prompted closer investigation of farmland acquisition by financialized agri-corporate investors in one ’Hot Spot’ (the New England North-West region), which through a deep dive into land title records identified 200,000 ha of farmland purchased by superannuation (pension) funds [12].

Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord GI*), based on percentage rate of rural land changing ownership annually, median of the period January 2004 to January 2020. Source: Pritchard et al. (2021).

Funding for this research project concluded in 2022, however in discussions with NSW DPI, it was agreed to lodge a new land titles data request for the 2020-22 period to assess trends during these COVID-19 affected years. By this stage, LPI had been renamed and restructured to Land Registry Services (LRS), reflecting the arrangements established by the 2017 private sector lease. After several months of back-and-forth discussions, lawyers for LRS advised the researcher and NSW DPI that the data could not be made available for data security fears. Previous arrangements (securing data through a Human Ethics Research Protocol which specified its maintenance in a university approved, password-protected server) were now deemed inadequate. The chief fear of LRS was the prospect of an outside location being hacked, and data being sold to create a ‘shadow register’ that could be manipulated and used to defraud the public. This is an extraordinary assertion in the context of an Australian Torrens register. Unlike a country like the United States where registration essentially just alerts prospective purchasers to the existence of interests in land, and there is a plethora of registers at local level, each Australian state has a single Torrens register that grants title. That act can only be done by the state, and so everyone uses the register to transact, and everyone checks the register. A private, shadow register which does not grant title and is not updated in real time would be of no value to the public. LRS proposed that if the researcher and DPI wished to pursue the project, the researcher would be required to be physically located within their premises, work under a supervisory agreement, and with no data being extracted from LRS servers. The cost of data being made accessible under these conditions was not confirmed; however, the researcher was advised it would be ‘significant’, and certainly not the nominal administrative fee that was in place previously.

Conclusion

For jurisdictions with reliable registers, as a Torrens register is, bulk land title data presents an alluring prospect to track land ownership change. This project encountered significant challenges in working with these data and found limits in their interpretive capabilities. Nevertheless, the project successfully generated important insights into the ownership of rural land in NSW, with lessons for potential future research.Whether future research will occur, however, is entwined within the political economy of land titles data provision. Concerns about data security and integrity by the private sector interests charged with maintaining the register have currently forestalled, or at least made difficult, research that seeks to utilise bulk data. In a narrow sense, public transparency of land titles data is not compromised by these changes. Any member of the public, including university-based researchers, can search the land titles register to find the owners of a land parcel. But it has thrown up new challenges for research that uses bulk data to identify trends.

[1] Mabo v Queensland (1992) 175 CLR 1 per Brennan J at 68-69. [2] A number of jurisdictions have been working to extend land ownership transparency beyond legal ownership to beneficial ownership. British Colombia has a Land Owner Transparency Act 2019 which seeks to reveal the beneficial owners of land that is legally owned by a trust, corporation or partnership. In 2022, the UK passed the Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022 which requires overseas entities who own UK property to identify their beneficial owners on a register. The main objectives were to ‘help combat money laundering and achieve greater transparency in the UK property market’ [UK Government (2023) Factsheet: Beneficial Ownership. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/economic-crime-and-corporate-transparency-bill-2022-factsheets/factsheet-beneficial-ownership] This has not occurred in Australia, but all states have had Torrens systems for around 150 years guaranteeing that at least legal ownership of land is clear. [3] Griggs M and Low R (2020) Privatisation, the Consensus Algorithms of Blockchains and Land Titling in Australia: Where are We Now, and Where are We Going? In: Grinlinton D and Thomas R (eds) Land Registration and Title Security in the Digital Age: New Horizons for Torrens (1st ed.). Informa Law from Routledge, pp. 294–314. DOI: https://doi-org.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/10.4324/9780367218171. [4] Zakout W and Anand A (2017) Is there a role for the private sector in managing land registry, World Bank Blogs. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/there-role-private-sector-managing-land-registry-offices (accessed: 19/10/2023). [5] Van Erp S (2020) Are Land Registers becoming Intermediary Platforms of Land Data? In: In: Grinlinton D and Thomas R (eds) Land Registration and Title Security in the Digital Age: New Horizons for Torrens (1st ed.). Informa Law from Routledge, pp. 283. DOI: 10.4324/9780367218171-19. [6] Van Erp S (2020) Are Land Registers becoming Intermediary Platforms of Land Data? In: In: Grinlinton D and Thomas R (eds) Land Registration and Title Security in the Digital Age: New Horizons for Torrens (1st ed.). Informa Law from Routledge, pp. 283. DOI: 10.4324/9780367218171-19. [7]. Rod T, Griggs L and Low R (2018) Big Data and Privatisation of Registers – Recent Developments and Thoughts from a Torrens Perspective, European Property Law Journal 7(2): 147-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/eplj-2018-0007. [8] Funk L (2020) Managing Public Data for Whose Benefit?: A Case Study Analysis of Accessing Land Titles in the Canadian Prairies (Master of Arts thesis). University of Manitoba: https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/handle/1993/35165. [9] See: https://rural-land-science.sydney.edu.au/. [10] Pritchard B, Welch E and Umana Restrepo G (2021) Rural Land Ownership Change in NSW, 2004‐20. Available at: https://rural-land-science.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/NSW_Report_final.pdf (accessed: 19/10/2023). [11] Pritchard B, Welch E and Umana Restrepo G (2021) Rural Land Ownership Change in NSW, 2004‐20. Available at: https://rural-land-science.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/NSW_Report_final.pdf (accessed: 19/10/2023). [12] Pritchard B, Welch E, Umana Restrepo G, et al. (2023) How to Financialized Agri-Corporate Investors Acquire Farmland? Analyzing Land Investment in an Australian Agricultural Region, 2004-19, Journal of Economic Geography 23(5): 1037–1058. DOI: https://academic.oup.com/joeg/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jeg/lbad008/7158567.