August 1, 2024

#18: Digitalization for Financialization – How New Agricultural Tools Are Facilitating Farmland Investment

Until recently, scholars have solely focused on the assetization of farmland by financial investors, somewhat unnoticing a parallel trend: the rise of investment into ‘digital agriculture’. Emily Duncan shows how finance’s run on AG tech is intimately entangled with financialization not just because it is pushed by financial investors, but also because AG tech is poised to reformat agriculture in such ways that it becomes more amenable to an effective assetization.

***

There is much hype around smart farming, Ag 4.0, and the digital revolution for agriculture. Each of these terms has been used to describe the development of a variety of tools known as ‘digital agriculture’. These tools include a range of technologies like sensors, robotics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, decision support systems, satellite imagery, drones, and more. The most significant characteristic of digital agriculture is the ability for these tools to collect, collate, and analyse massive volumes of agricultural data. While digital agriculture development has predominantly focused on industrial field crop production, it spans a range of agricultural sectors.

Digital agriculture has attracted significant capital to develop these technologies, both from long-standing agricultural firms and new start-ups, with a market valued at $18 billion USD in 2023 [1]. While the purpose of these technologies is often described as helping farmers make improved management decisions with more data, they have a range of other social effects. One of these is the growing connection between financialization and digital agriculture, as investors use digital tools to facilitate their acquisition and management of farmland. I highlight a few examples from our on-going research on this topic, focussing on how data sharing is occurring between digital agriculture companies and farmland investment firms and the development in platforms that incorporate agricultural data into their algorithmic decision-making about farmland properties. The consequences of the increasing links between digitalization and financialization include further consolidation of farmland, issues of farmer autonomy, and questions around agricultural data sovereignty.

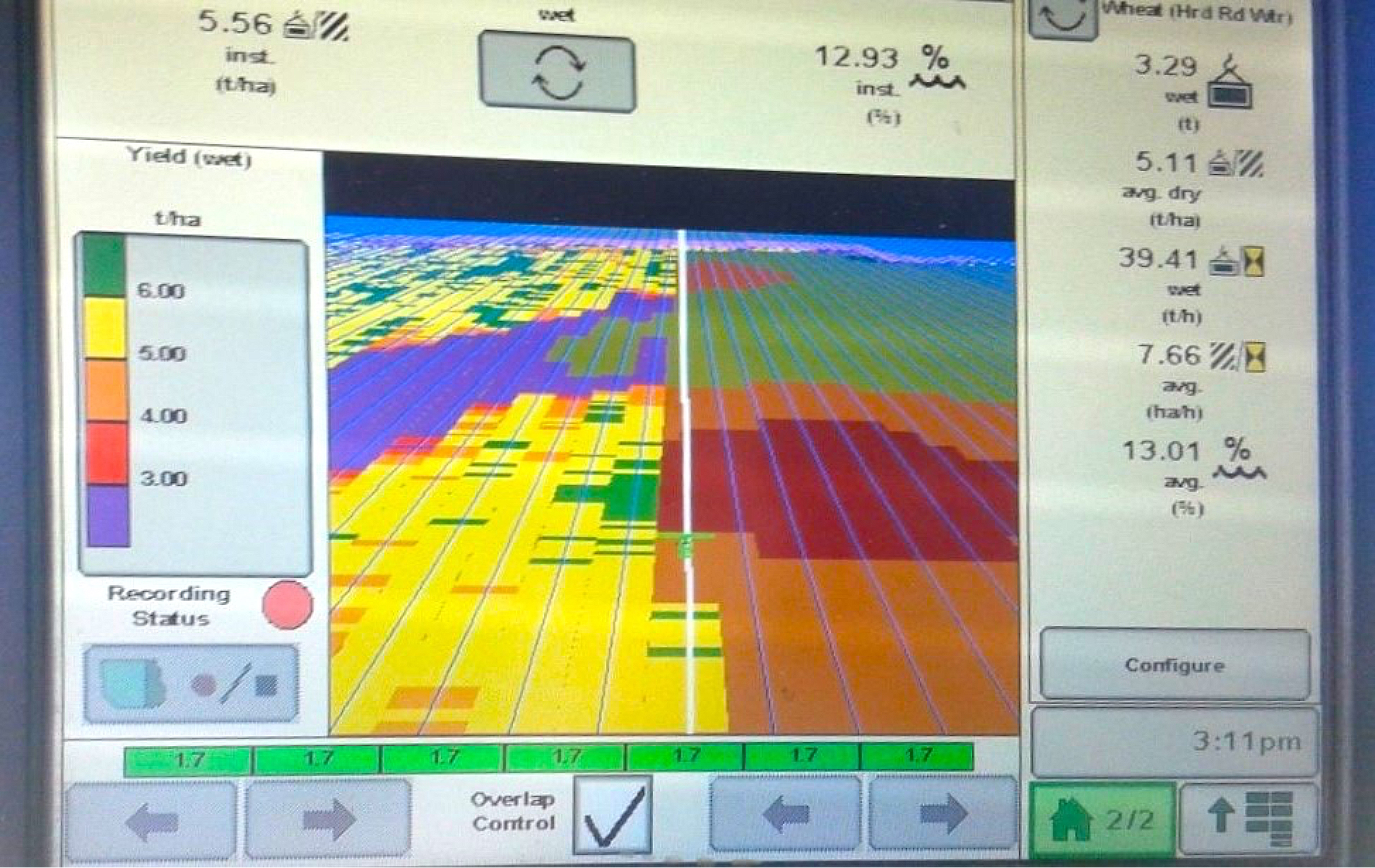

Example of a monitor display inside a combine cab actively collecting yield data layered on a soil map while the combine is automatically steered through GPS guidance. Source: Emily Duncan.

The data generated by digital agricultural tools increases the visibility of farmland to investors, meaning that through the generation of data they are better able to characterize and benchmark the property as an investment, as well as through real-time data collection actively verify the productivity of the farm through digital dashboards. Investor-owners may be located thousands of miles from their farmland, but through digital platforms, they can see what percentage of the field has been planted or harvested, which machinery is currently in use, and a variety of other farm data. Farmland has been characterized by investors as a long-term investment and as a hedge against inflation with a consistent rate of return [2]. Previously, what has made farmland a potential risk as an investment is a lack of transparency around management decisions and the quality of the farmland itself. However, digital agriculture increases the visibility and legibility of the land for investors by providing data on soil quality, weather patterns, yields, and management decisions.

Platforms and Partnerships for Data Sharing

Increasingly, we are seeing the creation of partnerships and digital platforms to facilitate data sharing for agricultural investment. In one notable example, Tillable – a digital platform that connects farmland owners with renters – promotes the collection of digital agricultural data as a means of increasing transparency between landlords and renters. This is a key feature of their platform and figures prominently in their marketing materials. In 2019, Tillable and The Climate Corp (owned by Bayer) – the creator of Climate Fieldview, a widely-adopted digital decision-support and data collection platform for farmers – announced a partnership to share data. Farmers raised objections to this partnership citing privacy concerns and loss of data ownership. Ultimately, the partnership was discontinued and Tillable had to rebrand the company completely, now operating under the name CamoAg [3]. A similar partnership was recently set up between Farmer’s Edge and Farmers National Company. Farmer’s Edge is a prominent digital decision support platform in Canadian agriculture (although the company has faced significant financial struggles and decreased acres enrolled) and U.S.-based Farmers National Company is a land ownership services firm [4]. Their partnership is meant to generate significant farm data with the intent to support the valuation of farm properties for investment.

Akin to the rapid consolidation of seed and input companies, the digital agriculture sector has recently seen numerous mergers and acquisitions. An example that illustrates the finance capital-digital agriculture nexus is when Granular, a digital agriculture subsidiary of Corteva Agriscience, sold AcreValue to Ag-Analytics for an undisclosed amount in 2021 [5]. Ag-Analytics is a digital agriculture platform with a comprehensive suite of precision agriculture tools. Their acquisition of AcreValue adds to this toolkit by incorporating a search database and platform of agricultural land sales in the U.S., including data on crop history, soil surveys, and mortgage data of individual parcels. Ag-Analytics has numerous partnerships with other large digital agriculture firms including John Deere Operations Center and Climate Fieldview. This example illustrates how the consolidation of platforms creates new opportunities for farmland investors to manage their assets.

Not only are there growing partnerships between digital agriculture companies and farm investment firms, but there is the increasing development of digital platforms for farmland investment. AcreTrader and FarmTogether are two platforms that aim to ‘democratize’ farmland investment by creating access to investment opportunities in crowdfunding and fractional ownership models with information on properties displayed through their digital portals [6]. These models differ from institutional farmland investment companies like Nuveen, where an asset manager selects a portfolio of farmlands on behalf of large-scale investors. By contrast, the platform-based farmland investment companies allow individual investors to browse properties online and invest based on lower minimum requirements. Institutional investment firms and the farmland platforms are similar in their use of digital agricultural tools that deploy artificial intelligence to screen potential properties and analyse farm characteristics related to soil fertility, water availability, and farm infrastructure. The emergence of these types of platforms can be seen as a type of platform capitalism [7] for agriculture, or in other words, the creation of digital spaces designed to enable the exchange of capital (i.e. farmland or agricultural data) and conduct business.

Digital farm data are facilitating the processes for farmland investment, as illustrated by the case of Fractal Ag, which has a unique business model. The U.S.-based company purchases a minority stake in farmland already owned by farmers, allowing the farmers to redeploy their equity to buy more farmland or invest in other aspects of their business. In a recent podcast [8], Fractal Ag’s CEO, Ben Gordon, highlighted how the company uses data from digital agriculture decision support tools to value potential farmland investments:

“You will submit to us what your yields were, you’ll share your my JohnDeere or your Climate [Fieldview] information to us, and we’re going to go through and we’re going to look at all the comps. We’re going to do a cap rate or rental rate analysis and we’re going to look at your data and if you outperform kind of like that static benchmark…we’ll pay.”This quote illustrates how agricultural data collection leads to benchmarking and, ultimately, the valuation of farmland for investors. In the process of farmland assetization, data sharing leads to increased visibility, legitimacy, and standardization [9].

What are the results of increased digitalization in the farmland assetization process?

Digital agriculture tools facilitate farmland assetization by providing data on farm properties and farm operators, leading to further consolidation of farmland through this process. It creates greater visibility for institutional investors as they acquire more information about land, leading to the growth of their portfolios. On the management side, farmland investors are able to monitor vast portfolios of land through technologies like remote sensing, satellite imagery, GPS, and agricultural data platforms. Additionally, digital investment platforms offering alternative financing enable farmers to expand their operations. Overall, these factors will accelerate the decline in the total number of farms and increasing farm sizes – an ongoing trend, but one likely to be exacerbated by these technologies.

The introduction of these technologies raises questions of farmer autonomy – to what extent will landowners expect farmer tenants to follow the prescriptive advice generated by the algorithms within decision support tools? It is increasingly likely that landowners may require tenants to adopt specific (and costly) digital agricultural tools in their management practices, providing a form of surveillance of investor assets. Farmer-tenants may be required to transfer the data generated by these tools to institutional investors, as codified in corporate standards of care or for ESG reporting. For example, Bonnefield is a farmland investment company operating a ‘own-lease out’ model in Canada, where they purchase farmland and then lease it back to farm tenants who operate and manage the farm. Bonnefield prescribes a set of farming best practices to its tenants who then must prove their compliance with these standards by sharing digital farm data [10].

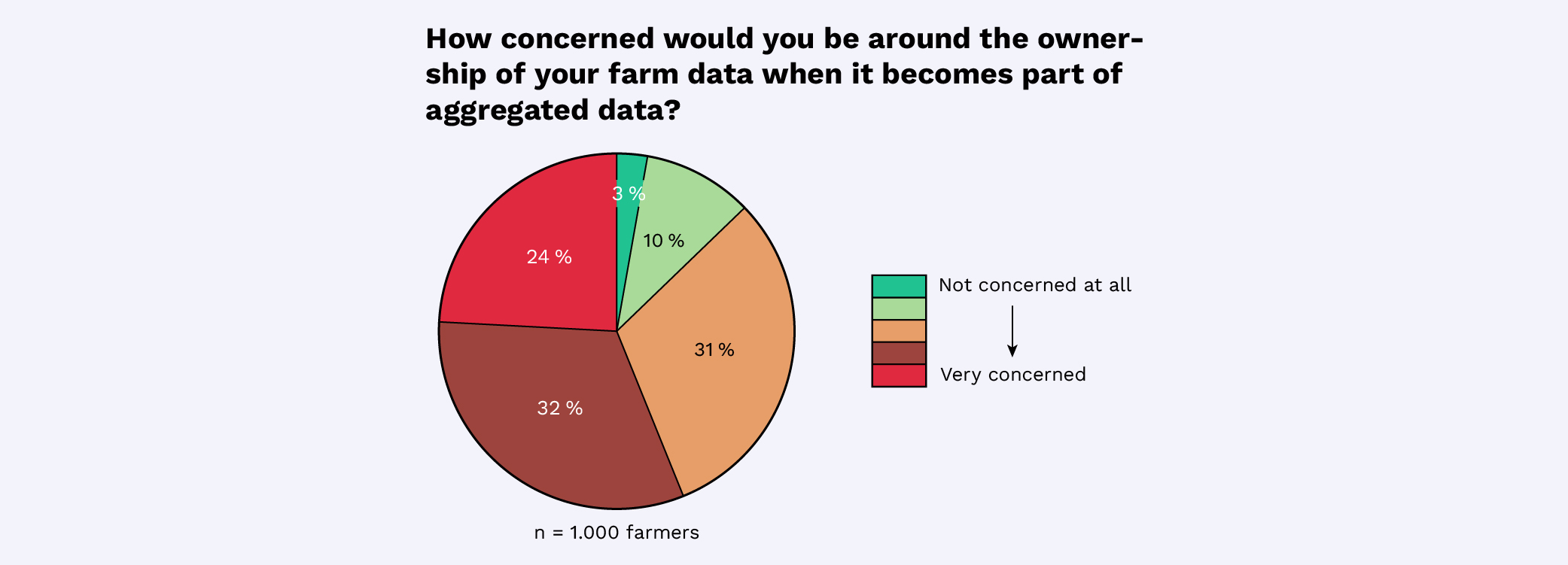

In a 2021 survey with 1000 farmers across 10 Canadian provinces, farmers shared their perspectives on agricultural data sharing, displaying high levels of concern about issues of ownership, especially when it becomes aggregated with data from other farms. For more information on the survey, see (Ruder 2023) [11] & (Duncan 2023) [12].

The use of digital farm data for farmland assetization may erode data sovereignty. Farmers have legitimate concerns about data ownership and the use of their agricultural data to determine land values when individual farm data becomes part of aggregated datasets. As digitalization and farmland financialization become increasingly intertwined, data sharing through various platforms and partnerships needs to be transparent to farmers. Collaborative efforts by government, industry, and farmer-led organizations are required to develop agricultural data governance mechanisms that can protect privacy and ensure fair practices in the farmland rental market. When data is used to define ‘top performing’ farmers, there is the risk that this may impact farmers’ ability to rent land from investors.

As farmland continues to undergo the process of assetization for global finance, it is key to pay close attention to the development of technologies that advance this transformation. Digital agriculture is promoted for its ability to allow farmers to make better management decisions to achieve both profitability and sustainability. However, the data generated by these technologies is valuable to a range of agri-food actors, including farmland investors [12]. As digital agricultural technologies continue to be developed and adopted, it will be important for researchers to question what agri-food futures they enable, especially around issues of farmland access and ownership.

[1] Kirin E (2023) Navigating the Global Landscape of Digital Agriculture. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2023/11/22/navigating-the-global-landscape-of-digital-agriculture/?sh=4737d3786c70 [2] Fairbairn M (2020) Fields of Gold: Financing the Global Land Rush. Ithaca [New York]: Cornell University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10330-5. [3] Duncan E, Rotz S, Magnan A, et al. (2022) Disciplining Land through Data: The Role of Agricultural Technologies in Farmland Assetisation. Sociologia Ruralis 62(2): 231-249. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12369. [4] Duncan E and Magnan A (2023) Exploring the Growing Links between Digital Agriculture, Finance Capital, and Farmland Investors and Managers in North America. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 29(2), 1-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v29i2.557. [5] Marston J (2021) Brief: Farm Data Company Ag-Analytics Acquires Land Research Platform AcreValue. Available at: https://agfundernews.com/ag-analytics-acquires-land-research-platform-acrevalue-granular-corteva#:~:text=US%20farm%20data%20company%20Ag,a%20statement%20sent%20to%20AFN. [6] Duncan E and Magnan A (2023) Exploring the Growing Links between Digital Agriculture, Finance Capital, and Farmland Investors and Managers in North America. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 29(2), 1-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v29i2.557. [7] Srnicek N (2017) Platform Capitalism. John Wiley & Sons [8] Nuss T (Host) (2023, October 31) A First-Principles Approach to Farmland Investing with Ben Gordon, CEO and Co-Founder of Fractal Ag (No. 311) [Audio podcast episode]. In The Modern Acre. https://themodernacre.com/ [9] Visser O (2017) Running out of Farmland? Investment Discourses, Unstable Land Values and the Sluggishness of Asset Making. Agriculture and Human Values 34(1): 185–198. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9679-7. [10] Bonnefield (2023) 2023 Responsible Investing Report. Available at: https://bonnefield.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Bonnefield-Responsible-Investing-Report-2023.pdf [11] Ruder S-L (2023) Agricultural Data Governance, Data Justice, and the Politics of Novel Agri-food Technologies in Canada (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). [12] Duncan E (2023) The Affordances of Digital Agricultural Technologies (Doctoral dissertation, University of Guelph).