January 30, 2025

#22 Tanzania’s Land Rush – A Zero-sum Game: Farmland Investments in Tanzania

Agri-investments often live through political regimes, and in cases of radical political change, the hopes of investors may be thwarted by unforeseen events and dynamics. With its recent turbulent political history, Tanzania offers unique opportunity to investigate the multilayered and changing politics of farmland investments. Joanny Bélair has taken up this task in her research and recent book “Tanzania’s Land Rush”, from which she reports. Joanny is currently research manager for the Canadian Bureau for International Education but was previously a research fellow at Utrecht University, working closely with LANDac. Her research agenda is focused on the political economy surrounding farmland investments in sub-Saharan Africa and their long-term resilience impacts on rural communities.

***

Figure 1: Village meeting, 2016, Photo taken by author

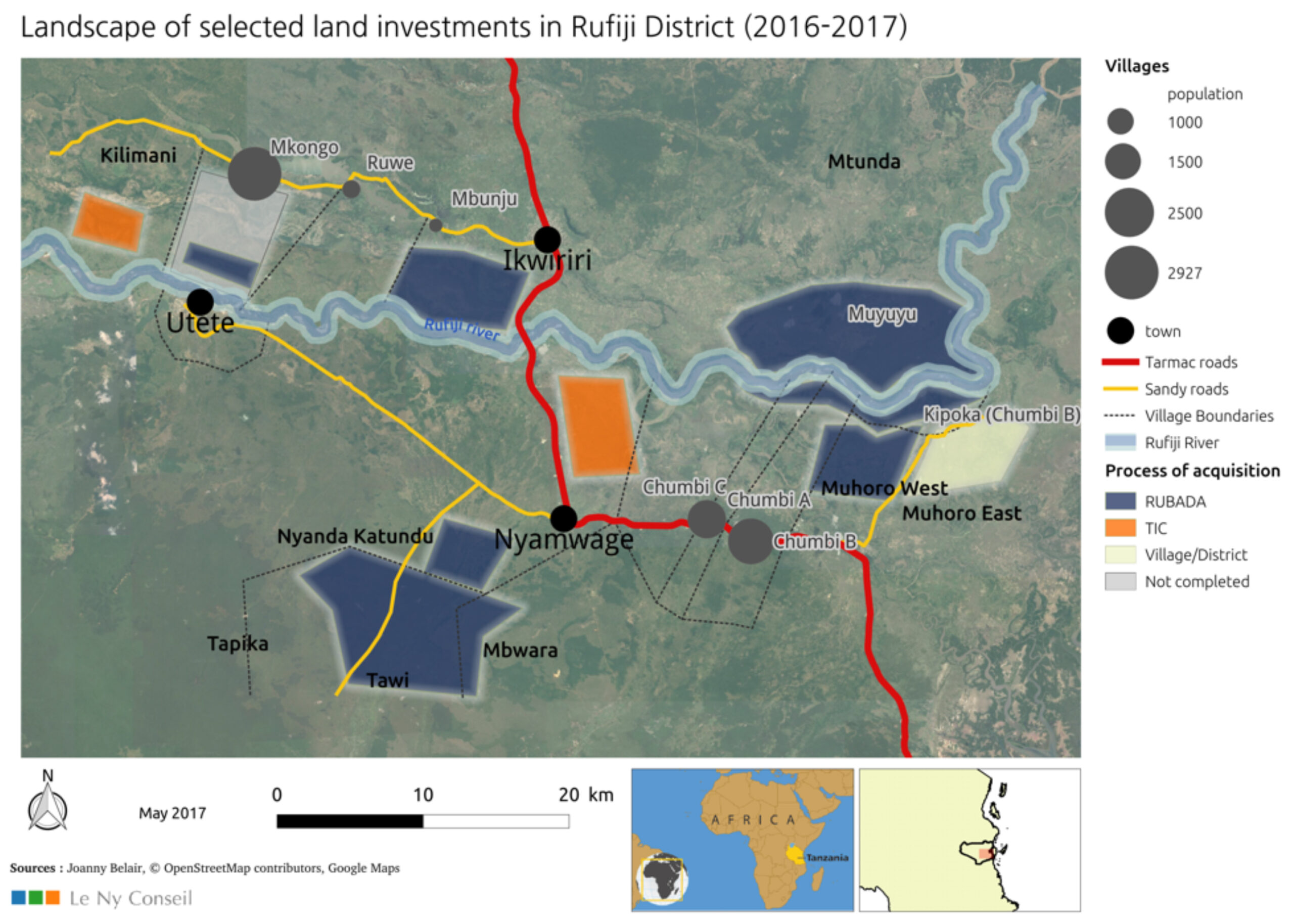

This website has repeatedly dealt with the politics and dynamics of farmland investments in Tanzania (see here and here), on which I shed further light by drawing on my book “Tanzania’s Land Rush. The book delves into the complex political economy associated with farmland investments in two highly targeted but understudied rural regions of Tanzania, Rufiji and Missenyi districts. The book aims at understanding the local impacts of farmland investments.

Figure 2: Joanny Belair, © OpenStreetMap contributors, Google Maps May 2017

It argues that to do so, we must unpack political struggles over land, capital, and authority, spanning from the national political arena to village-level politics. Indeed, farmland commodification led to new opportunities for economic or political gains, to which certain actors are given or negotiated privileged access. In addition, for a state such as Tanzania, which has weak infrastructural power [1] [2], land formalization and commodification are highly politicized processes because they participate in the creative process of state formation. The land rush has thus been seized by many actors as an opportunity to constitute their authority over the territory [3] [4] [5].

What can we learn from such an analysis? How do these political struggles shape local outcomes of land investment projects in rural Tanzania?

First, the nature of interactions between levels of governance – collaborative or competitive – is a key factor in explaining local outcomes. While in Rufiji, district officials voluntarily misguided central authorities to strengthen their authority and protect their financial interests with investors, the situation is different in Missenyi. A prominent land investor, Company X, for its part, has ensured its operational profitability through the protection it secured by cultivating clientelistic relations with government authorities at both national and local levels.

This led to rather different acquisition processes and local effects. In Rufiji, the affected villagers were unlawfully dispossessed through deception and false promises, arrangements behind land transfers are often secretive, and few of those projects are productive. The main impact on villagers is thus direct land dispossession. In Missenyi, the affected villages have been semi-included into a “bifurcated agrarian structure” [6] where they ensure their survival through the cultivation of their plots while at the same time selling their labour to capitalists who have acquired large parcels of land for mechanized production. They are disciplined through debt relations they contracted by participating in outgrower schemes, and the company manages to maintain its profitability through its established and protected monopsony in sugar production.

Second, the locally differentiated impacts of those investment projects tend to reinforce pre-existing exclusion dynamics. We must be careful with aggregated figures of local economic impacts. Empirical inquiry is necessary to measure whether and how an increase in household revenues benefits every member of the family household. In Missenyi, for example, many women have found their situation worsening since the arrival of the investor: now that their husbands are working for the company, they find themselves cultivating the familial plot alone, taking care of the family expenses without benefitting from their husbands’ new revenues. Indeed, although situations differ from one household to another, the fact remains that one of the unexpected effects of the arrival of Company X has been the explosion of local bars and prostitution.

Third, although all actors exert agency, not all actors are equal in their capacity to grasp investment-induced opportunities to renegotiate the structural constraints they endure. Their capacity to exert their agency depends on how much power they already hold in each institutional setting. Local peasants are often stuck between a rock and a hard place: in between global development orientations and the inner workings of the political economy of their country. Their land is being targeted by many powerful actors who dismiss them as significant actors and portray the way they use their land as unsustainable and unproductive.

Yet, all actors, even the less powerful ones, when they can secure both capacity and opportunity, may end up favoring their interests at the expense of others. For instance, in one specific village, I found that land investment projects led to local conflicts. In conflict case one, the local leaders defended their fellows in the land conflict, posing themselves as dispossessed victims and advocating for their rights to be acknowledged by the central government. In conflict two, the same village leaders colluded with district officials and the military to dispossess their fellow villagers. The process was particularly violent: in November 2017, all affected villagers were forcefully displaced, and their houses were burned down by military and district officials (see Chapter 7), thereby obliterating any wrongdoing from the authorities.

In fact, this analysis and investigation of the local impacts of six farmland investment projects in rural Tanzania led me to seriously question the success of land formalization programs in securing peasants’ land rights. Processes of land acquisitions are plagued with issues and consultations and compensation of affected communities are almost always problematic. Investments’ monitoring and evaluation beyond acquisition processes are also predominantly deficient. Local grievances are further aggravated when state authorities keep on defending unproductive or absent investors, at the expense of the community who has been dispossessed.

The book also highlights that political interference is a crucial problem in Tanzania. Numerous cases exemplify how state officials, investors and elites, and even sometimes local leaders, use their authority to interfere in farmland acquisition and land formalization processes to foster their economic interests. The land rush thus clearly produces winners and losers, and local communities tend to be more on the losing side.

Importantly, few of those investments I investigated are operational, and most of them have failed to deliver on their socio-economic development promises. Therefore, my book invites a more critical reflection on the assumptions that underpin global development orientations on land and socio-economic development. Persistent beliefs such as foreign investors are more productive than local farmers and African agriculture is characterized by its “intrinsic lower productivity”, its backward technology, and smallholders’ “slowness” to adopt modern farming do not hold when faced with the facts [7] [8] [9].

Furthermore, my book shows that many foreign investors are not competent and efficient. In fact, they are often ill-equipped and/or incompetent to undertake such ambitious farmland investment projects. Importantly, they are also political actors, and their motivations are messier and blurrier than assumed by mainstream narratives [10]. Why they acquire land if it is unlikely that it could be put into production remains a question that has to be thoroughly addressed.

If we fail to undertake this critical reflection, we risk continuing hurting more than helping those who should benefit from farmland investment/development projects. Until then, it should not be a surprise that peasants remain suspicious and keep resisting these grand development agendas. As Vercillo and Hird-Younger [11] put it: “[…] [peasants] make rational choices based on experiences of historical antecedence, including decades of failed development projects, elite corruption and mismanagement, degrading ecologies and donor hegemony.”

On a last note, my research took place under the Presidency of the late John Pombe Magufuli, a populist leader whose authoritarian tendencies reached their climax before the 2020 elections. Repression in the country heightened up with Magufuli’s oppressive tactics against the opposition, military presence, and the blocking of international media and external observers [12] [13] [14].

Unexpectedly, Magufuli, aged 61, died on March 17th, 2021, officially from heart complications. Rumors are that he died from Covid-19, ironically from the virus he so virulently denied. With respect to the Tanzanian constitution, the then vice-president, Ms. Samia Suluhu Hassan, has been sworn in as the new President to complete Magufuli’s five-year term.

Born in Zanzibar, Hassan became Tanzania’s first female president. Since she became President, Hassan has been distancing herself from Magufuli by taking a few significant steps. For instance, she reshuffled the government, fired the head of the tax authority, and appointed her own finance and foreign ministers. She also lifted the ban on media and pardoned overs 5,000 prisoners. On the economic side, she has moved away from Magufuli’s nationalist discourse, and adopted a more neoliberal approach. She pledged on stimulating the economy by revising investment policies, laws, and regulations to attract more investors [15]. Yet, observers were skeptical of her capacity to implement changes as her authority within the CCM remained fragile and the government was still crowded with Magufuli’s allies [16].

Nevertheless, in the few years that she has been in office, she has liberalized the political climate and carried on Magufuli’s fight against corruption by carrying out structural reforms, notably in the justice system. She has also been active on the diplomatic scene and managed to improve relations with international partners. On the economic side, she returned to business and investor-friendly reforms, which has led to an increase in international confidence, increased levels of direct investments and development loans [17]. On land issues, she recently took a significant step by establishing two committees to address land disputes to address long standing grievances of the Maasai communities in Ngorongoro district [18]. Although encouraging because it acknowledges those communities’ grievances, her intention seems to relocate/compensate Maasai communities rather than recognize their land rights. It thus remains to be seen how this government will address Maasai land rights claims and all other Tanzanians who have been dispossessed through this land rush to determine whether local communities’ land rights will be better protected under Hassan’s presidency.

[1] Mann M (1984) The Autonomous Power of the State: its Origins, Mechanisms and Results. European Journal of Sociology 25(2): 185–213. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975600004239. [2] Herbst JI (2000) States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (Princeton studies in international history and politics). [3] Lund C (2013) The Past and Space: On Arguments in African Land Control. Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute 83(1): 14–35. [4] Wolford W et al. (2013) Governing Global Land Deals: The Role of the State in the Rush for Land. Development and Change 44(2): 189–210. [5] Fogelman C and Bassett TJ (2017) Mapping for Investability: Remaking Land and Maps in Lesotho. Geoforum 82: 252–258. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.008. [6] Akram-Lodhi AH (2007) Land, Markets and Neoliberal Enclosure: an Agrarian Political Economy Perspective. Third World Quarterly 28(8): 1437–1456. [7] Christiaensen L (2017) Agriculture in Africa – Telling Myths from Facts: A Synthesis. Food Policy 67: 1–11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.02.002. [8] Sheahan M and Barrett CB (2017) Ten Striking Facts about Agricultural Input Use in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 67: 12–25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.010. [9] Snyder KA et al. (2020) “Modern” Farming and the Transformation of Livelihoods in Rural Tanzania. Agriculture and Human Values; Dordrecht 37(1): 33–46. Available at: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/10.1007/s10460-019-09967-6. [10] McCarthy JF, Vel JAC, and Afiff S (2012) Trajectories of Land Acquisition and Enclosure: Development Schemes, Virtual Land Grabs, and Green Acquisitions in Indonesia’s Outer Islands. The Journal of Peasant Studies 39(2): 521–549. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.671768. [11] Vercillo S and Hird-Younger M (2019) Farmer Resistance to Agriculture Commercialisation in Northern Ghana. Third World Quarterly 40(4): 763–779. [12] Taylor B (2020) Tanzania’s Election Results are Predictable. What Happens Next is Not. African Arguments. Available at: https://africanarguments.org/2020/10/tanzania-election-results-are-predictable-what-happens-next-is-not/ (accessed: 17/06/2021). [13] Al Jazeera (2020) Tanzania Opposition Loses Key Seats in Vote Marred by Fraud Claim. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/10/29/tanzania-opposition-loses-key-seats-in-vote-marred-by-fraud-claim (accessed: 17/06/2021). [14] France 24 (2021) Tanzania’s Magufuli, the “Bulldozer” President who Dismissed Covid-19. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210318-tanzania-s-magufuli-the-bulldozer-president-who-dismissed-covid-19 (accessed: 17/06/2021). [15] The Citizen (2021) President Samia Outlines Stimulus Plan. Available at: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/-president-samia-outlines-stimulus-plan-3373802 (accessed: 17/06/2021). [16] Ombuor R and Bearak M (2021) Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan Acknowledged the Pandemic and is Promising Change. Critics are Unconvinced. The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/04/07/tanzania-samia-suluhu-coronavirus/ (accessed: 17/06/2021). [17] Bertelsmann Stiftung (2024) BTI 2024 Country Report - Tanzania. Bertlesmann Stiftung Transformation Index. Available at: https://bti-project.org/de/reports/country-report (accessed: 05/01/2025). [18] Nyeko O (2024) Tanzania’s President Takes on Forced Evictions of Maasai Community. Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/12/05/tanzanias-president-takes-forced-evictions-maasai-community (accessed: 05/01/2025).