Players

In agricultural capital placements

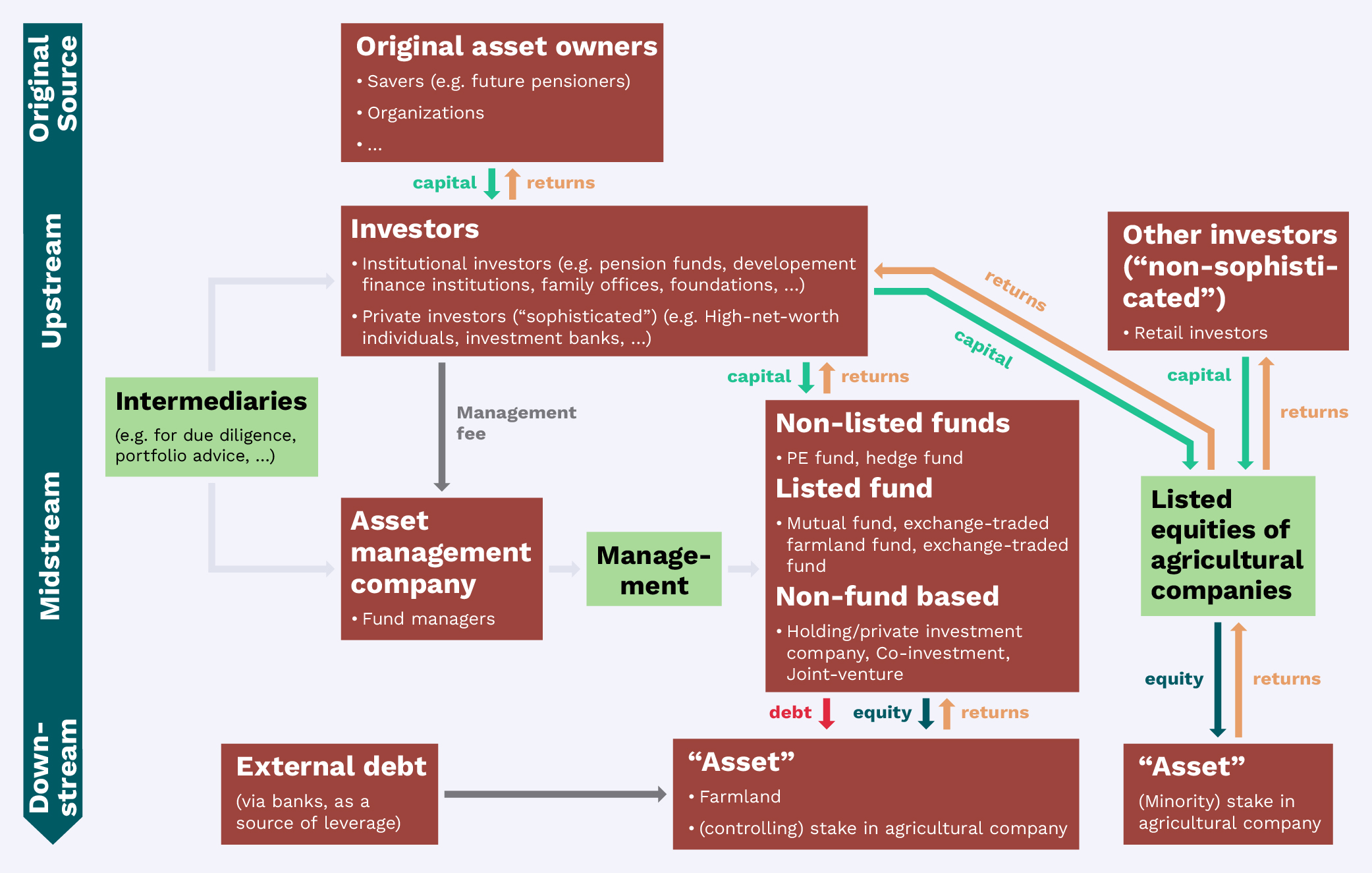

Actors along the agri-investment chain. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 59.

Actors along the agri-investment chain. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 59.

It is important to scrutinize the flesh-and-blood institutions behind “finance-gone-farming”. The so-called AG investment space is populated by a wide range of players: pension funds, insurance companies, investment banks, family offices, high-net-worth individuals, sovereign wealth funds and university endowments can be found here.

A good overview is provided in the figure above, which shows the dominant actors along the agri-investment chain.

A recent trend in the chain has also been that large agrobusiness companies – such as Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus; the so-called ABCD companies – set up PE subsidiaries. (for more information on the PE model, click here) This ensures more control of the agri-food chain and enables to them capitalize on in-house information and already-existing access to land in the world regions in which they operate. Also, state-backed players such as sovereign wealth funds or development finance institutions may provide debt, equity and/or risk insurance. For instance, half of the 54 PE funds with a focus on agriculture that were targeting the African market in 2013 were backed by development finance. Those development finance institutions see themselves as providers of patient capital in order to fill in the financing gap in regions with high barriers to accessing commercial institutional capital.

In the following, the most common players in the agri-investment chain are introduced.

(Ouma 2020: 52-59)

Pension funds

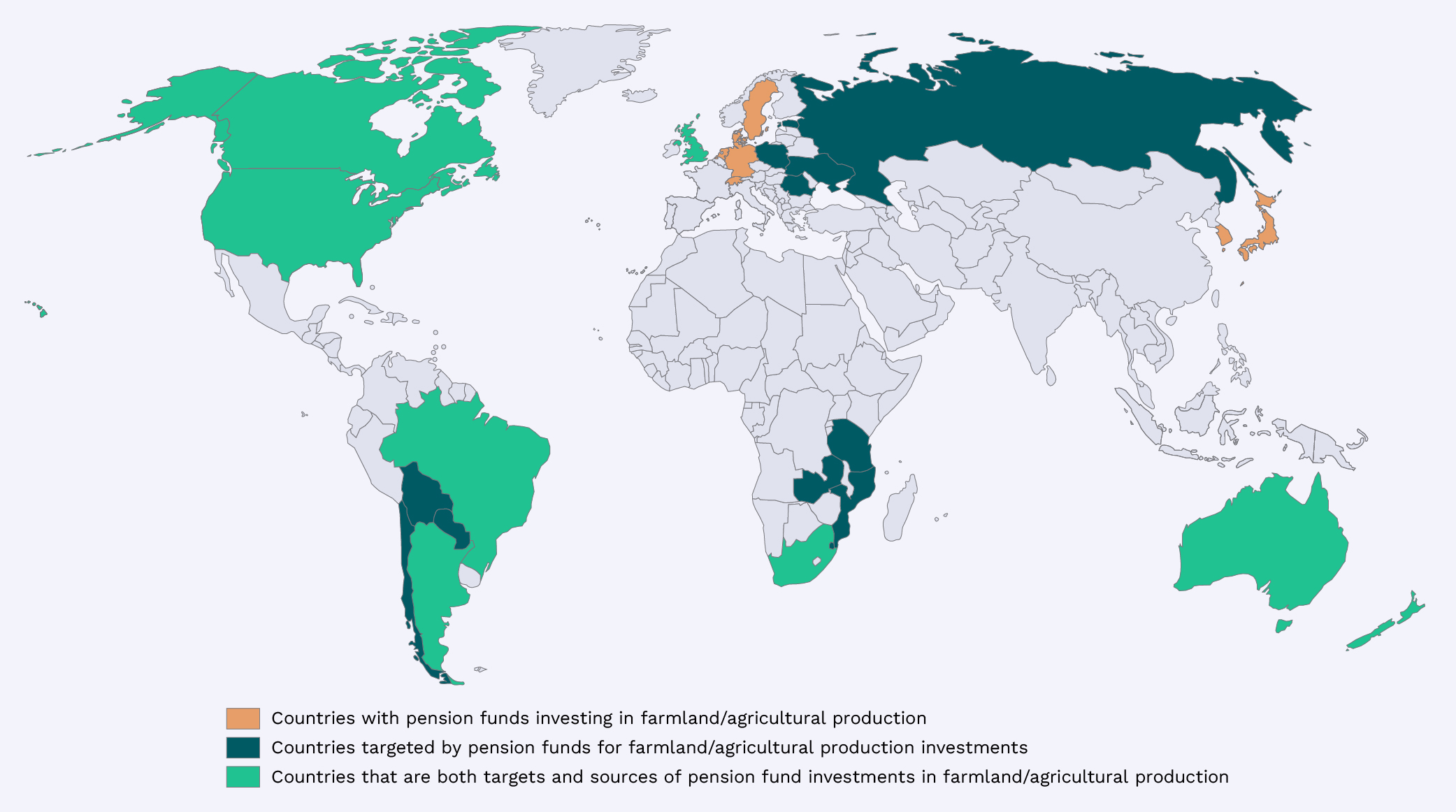

The geography of agri-investment-focused pension funds. Map modified after Grain 2018. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 54.

The geography of agri-investment-focused pension funds. Map modified after Grain 2018. Re-drawn from: Ouma 2020: 54. Pension funds are financial institutions that provide income to its investors during the time of their retirement. As institutional investors, they play a role in financial markets. They are probably the largest stewards of capital globally. The planet’s largest 22 pension markets alone managed a total of assets worth more than US$40,123 billion by the end of 2018. However, investments in agriculture are not the largest share of their investments: by mid-2018, about US$15 billion had been invested by at least 76 corporate and public pension funds in farmland and agricultural ventures.

From a geographical point of view, it is possible to trace the domicile of these funds as well as the countries most targeted by pension fund money. In the rare case of Aotearoa New Zealand, we can even trace where this money exactly lands (click here for more information)

Pension funds hold assets in trust for their clients (the future pensioners), but usually delegate the management of asset allocations, e.g., in farmland, to specialized asset managers. By doing so, they seek to capitalize on expertise not found “in house” and outsource the risks associated with generating returns. But not always: the US-American Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association (TIAA), one of the largest pension providers in the country, is also the largest global farmland investor today. TIAA launched itself two agricultural funds in the past, in which other investors were able to co-invest. In this case, the pension doubles as an asset manager and general partner.

(Ouma 2020: 52-58)

Other players

Insurance companies

Compared with information existing about pension funds’ capital placements into agriculture, it is less easy to get data on insurance companies. Nevertheless, global players like Munich Re and Allianz have made ventures in timberland and farmland part of their portfolios.

(Ouma 2020: 53)

Sovereign wealth funds

State-backed players can be found in the AG investment space, too. Sovereign wealth funds (e.g., the Chinese Investment Corporation) who may have initially focused on primary production, are increasingly investing along the whole food chain. They are joined by national and multilateral development finance institutions, which provide risk insurance and/or debt and equity to commercial investors who would otherwise not invest in more risky “frontier markets” (such as Tanzania).

(Ouma 2020: 55)

Endowments

Other key actors within the AG space are endowments, which administer the assets of wealthy individuals (e.g., Bill Gates), families (so-called family offices) or institutions such as universities. One good example in this regard is the Harvard Endowment Fund, which until 2016 was the largest endowment landowner in the world with capital placements in Aotearoa New Zealand, South Africa, Brazil, and North America. But as a new senior manager came into office, he wrote down the value of its farming and timberland portfolio from 13 percent of its endowment (US$39 billion in total) to 6 percent. What was behind this move?

(Ouma 2020: 64f.)

HNWI

High-net-worth individuals (HNWI) have also come to invest into farmland and timberland as individual investors. It is often difficult to discern whether these invest in individual capacity or via a family office.

(Ouma 2020: 53)

Solving the equity puzzle: Opening agricultural investment for the masses?

In addition to so-called sophisticated investors who possess knowledge of financial markets, the AG investment space has been made more accessible to mom-and-pop investors (‘other investors in the figure). These are retail investors who increasingly populate global financial markets owing to the massification of financial investments among the global middle class. They access the AG investment space through vehicles such as mutual funds. One alternative for retail investors is the acquisition of shares in listed agribusiness companies, which nowadays may also be featured in agri-focused exchange-traded funds. These are funds investing in several companies involved in agricultural or livestock production. Some of the agricultural companies, such as Sweden-listed Black Earth Farming, operating in eastern Europe have been established solely to capitalize on the rising interest in farmland. Some of the publicly listed structures may also adopt the form of a real estate investment trust, “a mutual fund-like structure that distributes at least 90 percent of its income to investors and is generally exempt from corporate income taxes” [1].

The “pioneer” of these trusts (which may also be called exchange-traded farmland trusts: ETFTs) was Gladstone Company, going public in 2011. Bonnefield in Canada and Farmland Partners in the United States would soon follow. These schemes represented the first attempts at securitizing farmland in order to solve the asset’s class “equity puzzle” (Sherrick et al. 2013: 27 [2]). These innovations promised to bundle income streams from the leasing out of several individual farming properties into a single vehicle that can be listed publicly and into which investors can buy in and out, as they please. The legal battles surrounding Farmland Partners, however, have undermined the faith in “agricultural REITs”. (It should be said though that the latter has seen rising values on the NYSE since late 2020).

(Ouma 2020: 55-58) [1] Fritz M (2010) First publicly traded farmland fund to be launched. Available at: www.beefmagazine.com/business/first-publicly-traded-farmland-fund-launched-1201 (accessed 2 January 2015). [2] Sherrick BJ, Mallory ML and Hopper T (2013) What is the ticker symbol for farmland? Agricultural Finance Review 73 (1): 6–31.