November 29, 2024

#20: Who Owns the Land? An East German Perspective

Clemens Jänicke, a geographer, and Daniel Müller, an agricultural economist, tackle the question of who owns the agricultural land in the federal state of Brandenburg in northeast Germany, part of former East Germany. The research has been conducted as part of the research unit FORLand, which examined whether land markets fulfil their societal functions in Germany and Austria and how land market regulations can respond to societal expectations and enhance market outcomes. To shed light on how ownership is distributed, Jänicke and Müller analysed the cadastre of all agricultural parcels [1]. They connected the ownership from the cadastre to company network data to reveal if several owners belong to one parent company and, through this conglomeration, may be able to exert market power on the land market, such as by influencing land prices. This brief intervention summarizes their findings and highlights pertinent differences between the concentration in cultivation and ownership.

***

Rising Prices for Agricultural Land in Germany

For several years, the agricultural land market in Germany has been the focus of a heated debate, which resulted in calls for stronger regulation of it to reduce land prices, avoid land concentration, and improve access to land for farmers with few financial means. The sharp rise in land rental and purchase prices since the economic crisis of 2007/08 and the rising competition for land have fuelled this debate. In the wake of these changes, there has been a growing number of reports about an increasing concentration of land in the hands of a few, often capital-rich corporate players, accompanied by concerns about welfare losses due to the market power of the large landowners. In Germany, land acquisitions by non-agricultural investors, i.e., investors not engaged in farming or originating from a sector other than agriculture, have received growing attention [2]. However, empirical evidence on land ownership patterns and land concentration remains weak. Our goal was to quantify who owns the agricultural land in Brandenburg and reveal the concentration of land ownership. This complements previous insights offered on this website, such as those from André Magnan and Annette Aurélie Desmarais or Bill Pritchard and Cathy Sherry. Our study is the first comprehensive analysis of the ownership structure and ownership concentration for all agricultural land (1.3 million hectares) in Brandenburg, a large federal state in former East Germany.

Combining the Land Cadastre with Information on Company Networks

Our work relied on land ownership data for every parcel of agricultural land obtained from the cadastre of the year 2020. We faced the challenge of identifying the true owners of companies, as the cadastre only lists the companies holding the land titles but not their global ultimate owners (i.e. the entity that owns the major share in a company). Loka Ashwood and Phil Howard noted similar challenges in this blog, and Sommer and de Vries describe this problem for Germany very nicely [3]. To account for the ultimate ownership, we combined the cadastre with information on company networks from the company database DAFNE, which covers all German companies. Linking individual ownership to company data reveals the true ultimate owners.

Revealing the influence of company networks on ownership concentration was motivated by reports about share deals (e.g. [4] or [5]) that obfuscate the true ownership of companies. Share deals are acquisitions of between 51% and up to 94% of the shares of agricultural enterprises. The share deals allow the buyers to take control of large tracts of land but without being tied to the Land Transfer Act (Grundstückverkehrsgesetz) [6]. In that way, buyers can avoid paying land transfer taxes, and the land acquisition is not publicly reported. This comes at the cost of transparency and substantial foregone tax income.

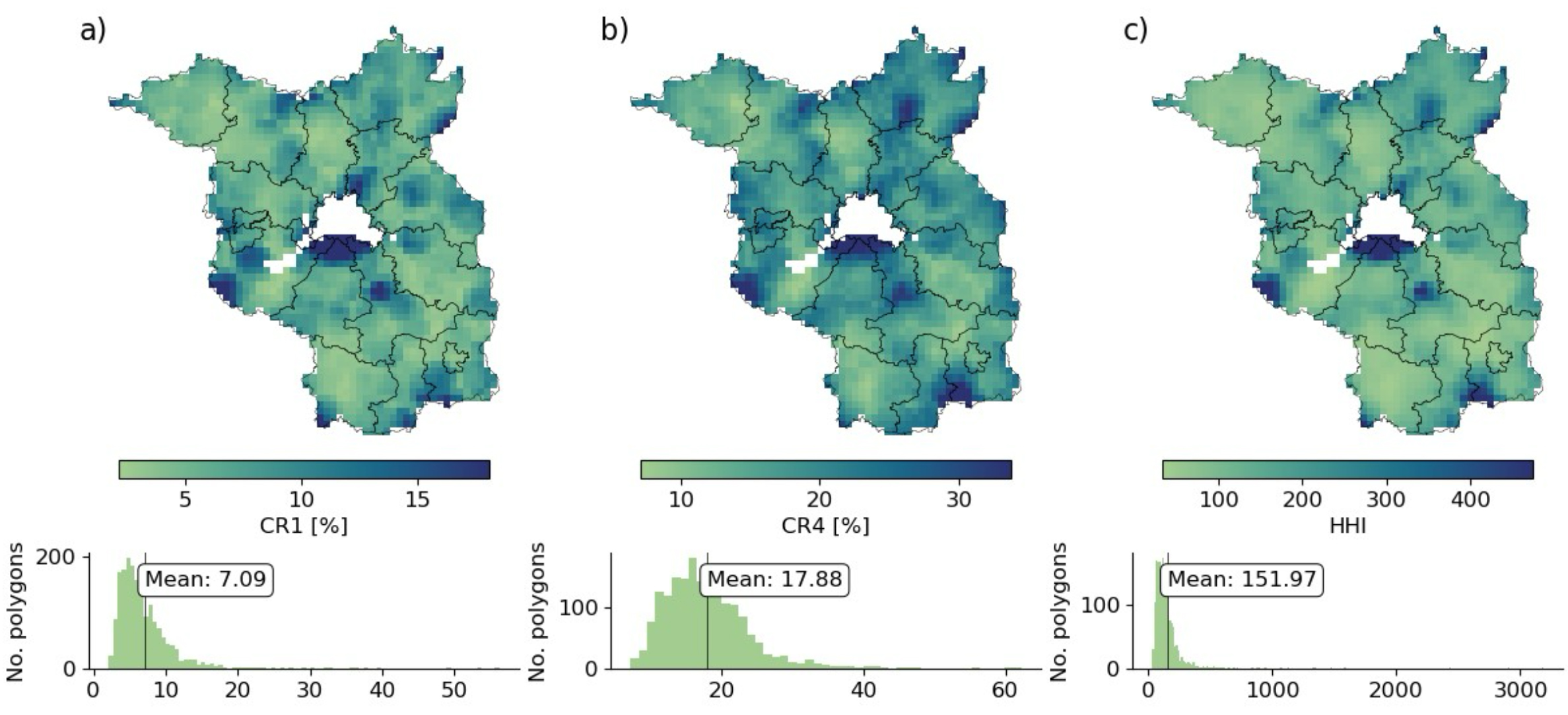

We grouped all landowners into distinct categories, including private persons, single companies, and company networks, based on whether or not the owners are active in agriculture. We aggregated the land of all landowners and companies that belonged together to quantify ownership concentration. As land is an immobile asset, we considered only local land markets to calculate ownership concentration. Plogman et al. (2022) [7] found that 90% of all land transactions in Brandenburg occur within a radius of 12 km. Therefore, we looked at a grid of overlapping subregions that we defined as circles with a radius of 12 km. We calculated common concentration measures for each subregion, such as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and concentration rates.

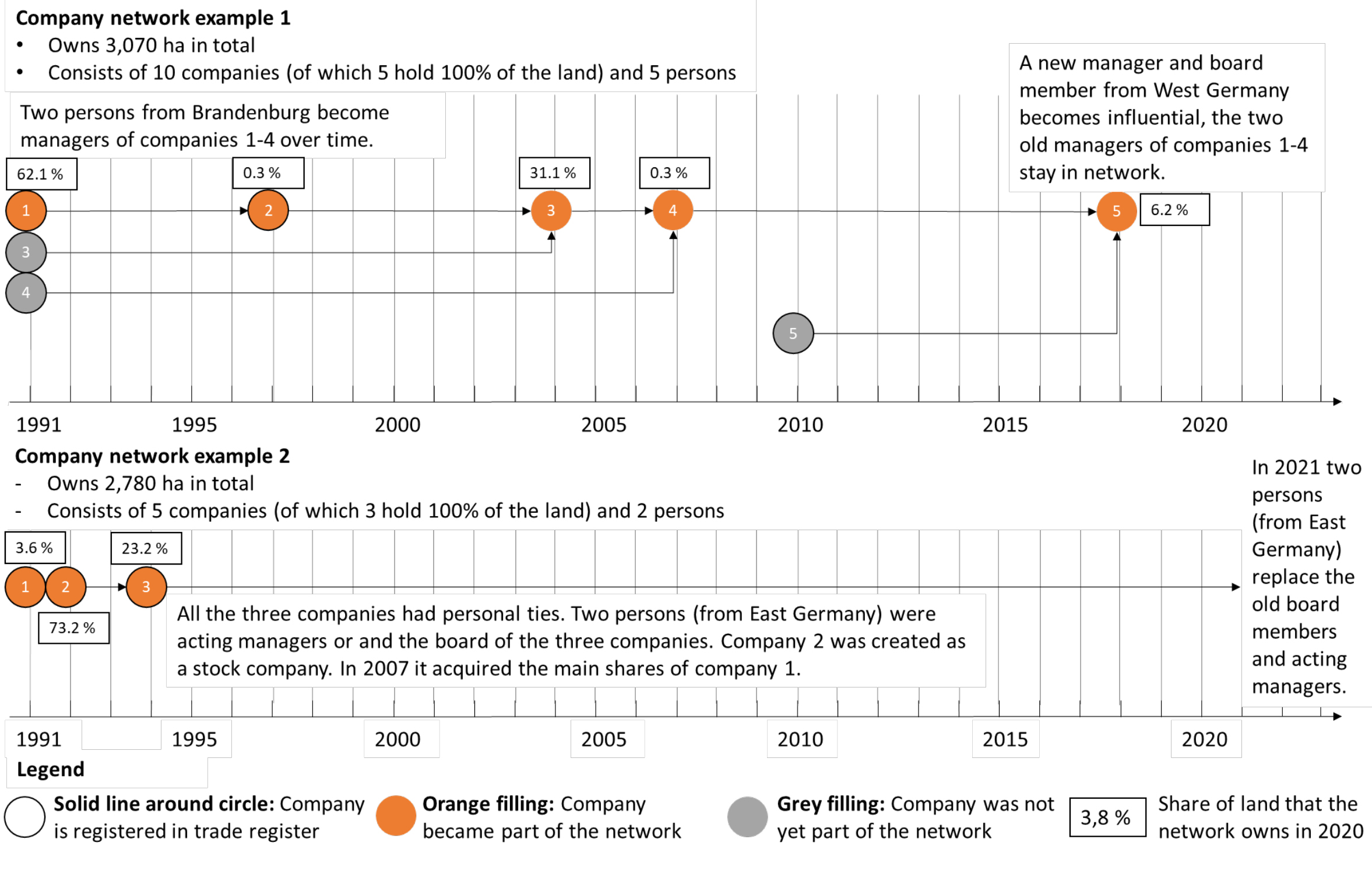

We were motivated to assess the influence of all non-agricultural landowners on the ownership concentrations in an automated way. However, this was difficult, especially for the company networks. Although there was a plethora of information on the companies, company networks were similar in their composition, prohibiting an automated rule-based assessment. For example, some networks, which developed from the old agricultural production cooperatives of former East Germany, looked very similar to networks of farms, which (non-)agricultural investors acquired over the last 30 years. Eventually, we manually investigated the largest company networks by analysing the shareholders and managers of the landholding companies that were part of the respective networks. Figure 1 exemplifies how we recorded this analysis. With this procedure, we could distinguish between different types of networks.

Figure 1: Examples of the history of two company networks that own land in Brandenburg. Each dot represents a company. The solid lines indicate the timing of registration in the trade register. The orange filling indicates the year the company became part of the network. A grey filing indicates that the company was registered that year but was not directly part of the network. The numbers indicate the share of land the company owns in 2020.

Many Individual Landowners and Low Concentration in Land Ownership

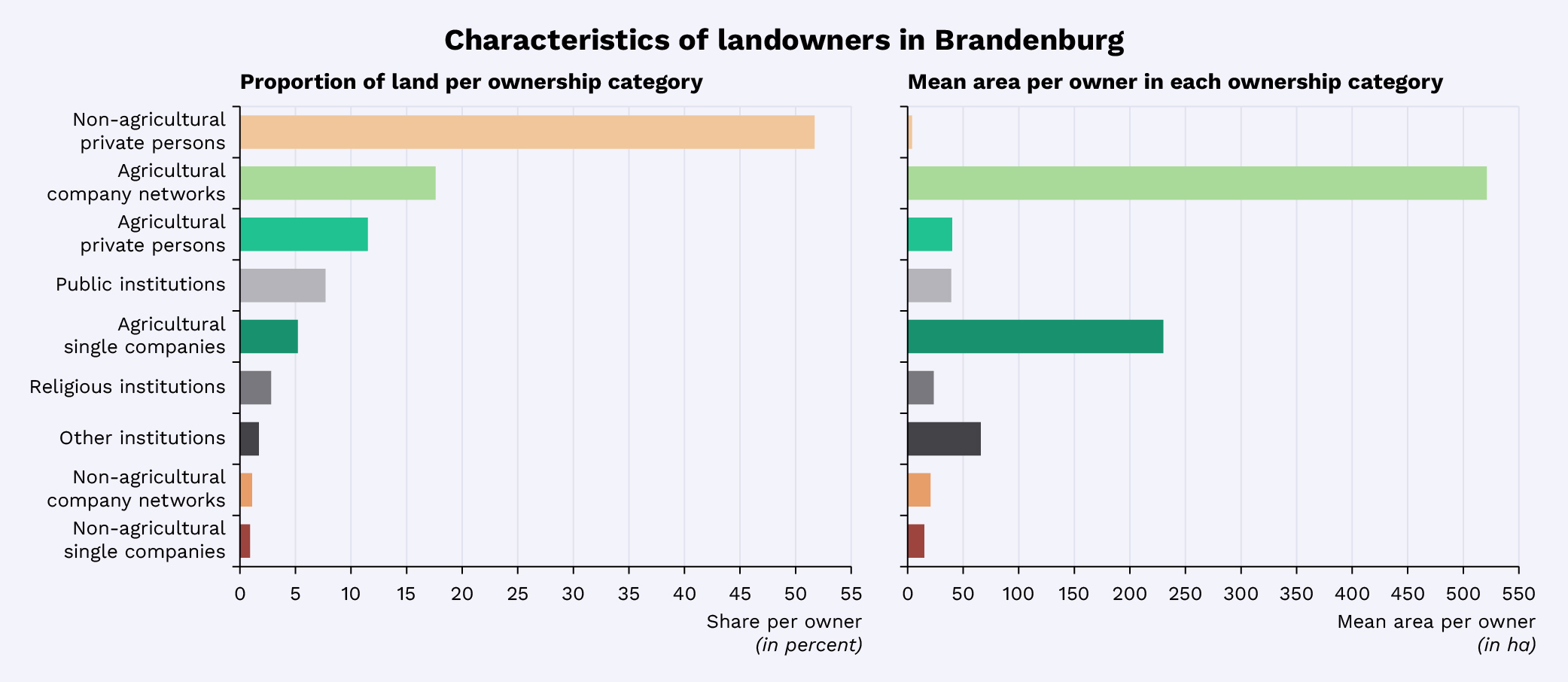

Our results show that ownership is broadly distributed and highly fragmented, while at the same time, land use is highly consolidated and characterized by large fields and farms in Brandenburg. We find 185.278 owners of agricultural land, of whom 174.860 are private persons who are not agriculturally active and own, on average, 7 hectares (Figure 2). Agricultural company networks own 18% of all agricultural land and have the largest properties, averaging 521 hectares per company network. In contrast, the 5,413 farms registered farms in Brandenburg use (as opposed to “own”) an average size of 242 hectares and an average field size of 8 hectares.

Figure 2: Characteristics of landowners in Brandenburg: a) proportion of land per ownership category; b) mean area per owner in each ownership category.

We find only moderate ownership concentration. The largest owners own, on average, only 7% of the land within the subregions, and the HHI is 146 on average (Figure 3), which can be considered low compared to a maximum achievable concentration of 10,000. The largest landowning company networks exhibit above-average concentrations in the areas where most of their land is located. Depending on the company network, their share of land varies between 7% and 27% in these regions. We found very high shares of 69% only for one public landowner, a public company that administrates all agricultural lands of the city of Berlin. We concluded that the suspicion of excessive ownership concentration of agricultural land, allegedly caused by non-agricultural investors or capital-rich company conglomerates, cannot be confirmed for Brandenburg.

Figure 3: Spatial patterns and histograms of the concentration of land ownership for local land markets (calculated with 12 km buffers around the centroids of the grid cells). a) CR1; b) CR4; c) Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI).

Difficulties of Interpreting Concentrations

It is, however, difficult to interpret these numbers. To our knowledge, no established link exists between a certain level of ownership concentration and a specific positive or negative social, economic, or ecological outcome. One option was to compare our results against common market concentration thresholds. For example, the German law against competition restraints (Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen) [8] considers a share of over 40 % of the largest market actor as a dominant market position. However, these thresholds originate from other goods markets, but land markets exhibit distinct characteristics. Land is, for example, an immobile resource and not every piece of land is therefore of interest to every market player. In addition, farmers prefer to concentrate their land around their farmsteads to minimize transport costs, which leads to a natural concentration of agricultural land around farm centres. Thus, the thresholds from other markets only serve as an orientation and should be interpreted carefully. Using these thresholds, we find no clear signs for the existence of market power. One reason likely is that ownership of the largest landowners extends over many non-neighbouring regions in Brandenburg, leading to low local ownership concentration. When looking at larger areas, the concentration does not increase as the reference area rises more than the relative ownership share of single landowners.

We also looked for alternative ways of interpretation. One option is to compare our concentration with concentration from other studies, but this has its own problems. First, quantitative examinations of land ownership concentrations for larger areas are rare; hence, few comparable measures exist. Second, the reference areas for which the concentration measures were calculated differ, making a direct comparison difficult. Third, the regions have different histories and overall agricultural structures, which puts the concentrations in a different light. Last but not least, we found that concentrations were often calculated based on reported farm sizes from public statistics. However, farm sizes, which refer to the area of cultivated land, do not necessarily overlap with ownership, as farms often cultivate partly owned and partly rented land. It is, therefore, important to clearly distinguish land ownership from land use. This is particularly evident in Brandenburg, where, for historical reasons, land use is consolidated while ownership remains highly fragmented until today. All this highlights that further investigations are necessary to ensure a better interpretation of the concentration measures.

A Look Forward: Combining Ownership Data with Farm Data

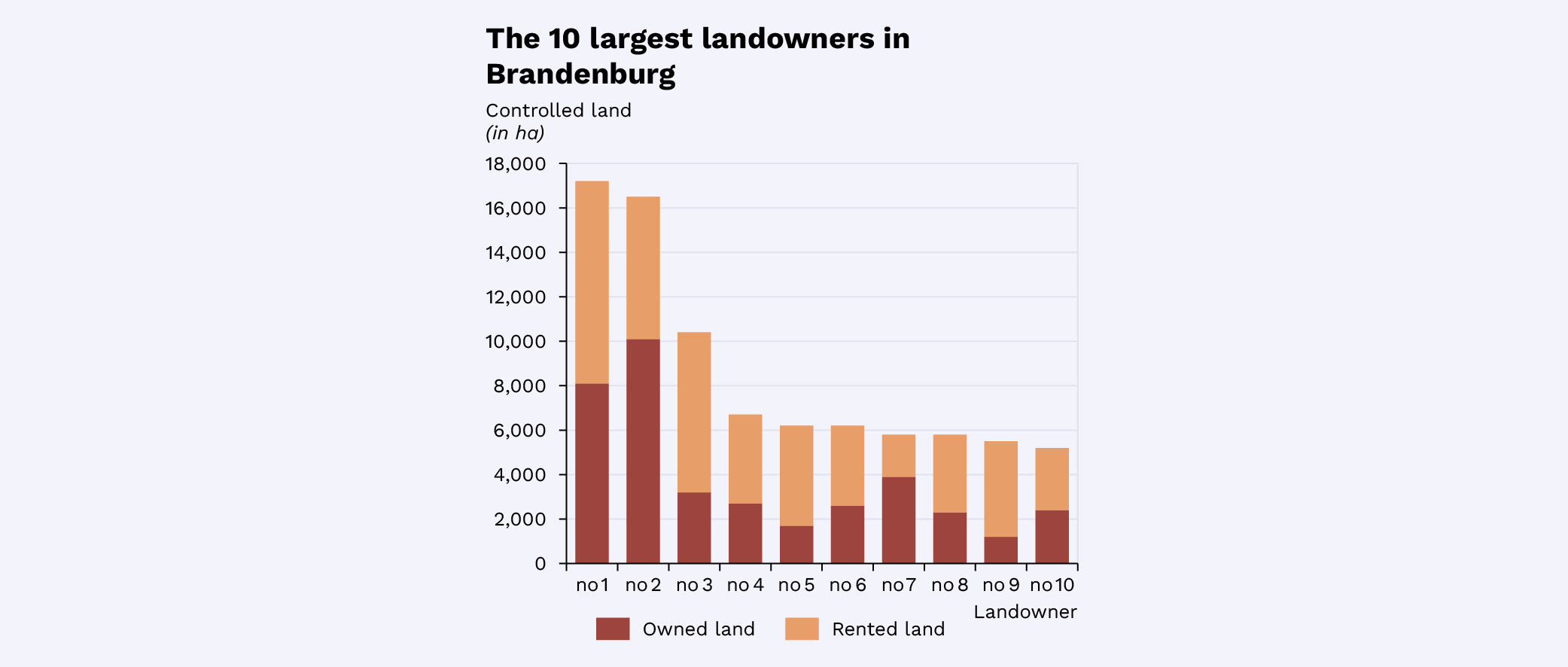

Although most studies do not pay attention to the distinction between owned and cultivated land, we argue that it is worth looking into this more. Quantifying how much land a landowner owns and how much they rent would indicate how much land they control. This was beyond the scope of our study, but we could have a first look into this, as we had access to a dataset with information on field and farm sizes and locations for all farms in Brandenburg [9]. Because the farm data did not include names, we needed to make assumptions about the farm owners, but for the largest agriculturally active landowners, we were able to identify their farms [10]. The results indicated that the largest landowners (most were company networks) control much more land than registered only in the cadastre and aggregated by us (Figure 4); some have even tripled the land they control. This shows that a combined look at land ownership and cultivated land could reveal further aspects of land concentration. The major hurdle for such kind of analysis is likely the access to data for most regions.

Figure 4: The largest 10 company networks ranked by the amount of land that they control. The controlled land consists of owned and rented land.

Conclusion

Our results show that the concentration of ownership in Brandenburg is not excessively high, which contrasts with public perception. We suspect that the perception differs for two reasons: First, the changes in the ownership structures over the last 30 years indeed show a trend toward rising land concentration. However, we cannot shed light on this because access to the cadastral data and company data is costly. Yet, different time slices of the cadastre are required to obtain insights on changes in ownership concentration over time (one could even say that the costs are prohibitive, as Magnan and Desmarais have already noted). Improved access to the cadastre and the farm data would be needed to create more transparency. On one hand, this would benefit research on land ownership changes, on the other, it also would balance the bargaining power of the market participants, which is a lever against market power [11]. Second, we suspect public perception is shaped more by individual cases of spectacular share deals that appear in the news, with highly consolidated and visible land use outcomes, as opposed to Brandenburg’s predominant fragmented ownership structure. This underscores that an integrated view of land use and ownership concentration over larger areas is necessary to obtain a complete picture of conditions on the land market.

[1] Jänicke C and Müller D (2024) Revealing agricultural land ownership concentration with cadastral and company network data. Agriculture and Human Values. DOI: https://10.1007/s10460-024-10590-3 [2] Tietz A, Forstner B and Weingarten P (2013) Non-agricultural and supra-regional investors on the German agricultural land market: An empirical analysis of their significance and impacts. Journal of International Agricultural Trade and Development, 62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.232334 [3] Sommer Fand de Vries W-T (2023) Values and representations in land registers and their legal, technical, social effects on land rights as an administrative artefact. Land Use Policy, 135, 106946. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.10694 [4] https://www.agrarheute.com/management/finanzen/agrarholdings-kaufen-freie-landwirtschaft-westen-585374 [5] https://taz.de/Landgrabbing-in-Brandenburg/!5916810/ [6] Grundstücksverkehrsgesetz (GrdstVG). 2008. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/grdstvg/BJNR010910961.html. Accessed 30 July 2024. [7] Plogmann J, Mußhoff O, Odening M, et al. (2022) Farm growth and land concentration. Land Use Policy, 115, 106036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-024-10590-3 [8] Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen § 18 Marktbeherrschung. 2013. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/gwb/__18.htm. Accessed 17 May 2024. [9] The farm data stem from the Integrated Administration and Control System (IACS) of the European Union. The IACS administrates the agricultural subsidy applications of farmers. Each farmer that applies for subsidies has to indicate the field boundaries and the crops planted on the field. Via a unique identifier of the farmer the fields can be used to determine the location and extent of the farms. [10] We assumed that the landowner owning most land that is cultivated by a farm is the farmer unless they have more land in another farm. [11] Balmann A, and Odening M (2021) Lassen sich regulatorische Eingriffe in Bodenmärkte mit Marktmacht und Flächenkonzentration empirisch begründen?. FORLand Policy Brief.